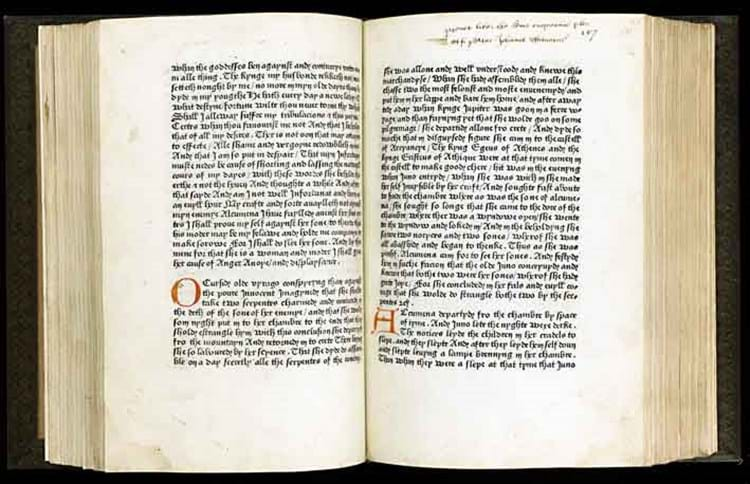

The Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye was not just the first book printed in English, but the first printed or published by an Englishman, William Caxton. It is also his very own translation from the French of an epic romance by Raoul Lefèvre.

Only 18 copies survive, of which only two are complete and only six remain in private hands.

The copy sold at Sotheby's on July 15, which in its period style but 19th century binding has eight leaves in facsimile and others supplied from another, shorter copy, along with a number of restorations and repairs, was the first seen at auction for 12 years.

In 2002 the Beriah Botfield/Longleat copy made £600,000 at Christie's and back in 1998, the Wentworth Library copy made £700,000 at King Street.

Commercial Opportunity

The book itself was remarkably ambitious achievement for what was a first attempt at a still relatively new art, it also proclaimed "...a remarkable confidence in the English vernacular [and] ...is an extraordinary fusion of traditional courtly patronage and forward-thinking commercial opportunism", said the cataloguer.

Printing had begun only 30 years earlier and in a world where Latin was still the universal language of scholarship, religion, law, etc, printing in the vernacular, which had to rely on a smaller domestic readership, was still in its infancy. The first book printed in German had appeared only in 1461, the first in Italian in 1470, while the first in printed book in French did not appear until 1476.

No date or place of printing is given for this Recuyell.. . and although the book has traditionally been assigned to Colard Mansion in Bruges, c.1475, more recent research by Lotte Hellinga indicates that it was printed towards the end of 1473 or early in 1474, and that Caxton's technical help with printing was supplied by a Ghent workshop connected with a well-known scribe, David Aubert.

The typeface seen in Caxton's first few publications is very close to Aubert's handwriting.

Myth and Chivalry

Like its earlier companion, Lefèvre's Histoire de Jason of c.1460, the Recuyell... turned the heroes of Greek myth into chivalric figures, and both had been written within the context of the literary and ceremonial traditions of the Burgundian court, which at the time was the cultural centre of northern Europe.

Lefèvre had dedicated ...Jason to Duke Philip the Good, who then commissioned the Trojan history. His heroes were the mythical founders of the Burgundian dynasty and featured in court ceremonies ranging from the chivalric Order of the Golden Fleece to the plays on the life of Hercules staged during the 1468 wedding celebrations of Duke Charles the Bold (Philip's successor) and Margaret of York.

Begun that same year in Bruges and completed three years later in Cologne, Caxton's translation was a diplomatic gift to Margaret, who, crucially for his future success and patronage, was the sister of Edward IV of England.

A leading figure in the English mercantile community in the Low Countries, and someone who had almost certainly been involved in the marriage negotiations of Margaret and Charles, Caxton does not, however, appear to have had any previous experience as a translator and his epilogue notes that "...in the wrytyng of the same my penne is worn, myn hande wery & not stedfast, myn eyen dimed with overmoche lokyng on the whit paper".

Producing something in the hope of securing further commissions or other royal favour was a well-established courtly gesture, in Burgundy as elsewhere, but although it is unlikely that Caxton originally intended his translation to be printed, he had come to believe that it would appeal to wealthy and aristocratic circles in England and must have hoped that the patronage of the King's sister would help sales if it were to be printed.

Caxton's Epilogue

There is also no doubt that Caxton had recognised the huge potential of the printed book, and his excitement at the novelty of the process is also reflected in the epilogue:

"...I have practysed & lerned at my grete charge and dispense to ordeyne this said book in prynte... [it] is not wreton with penne and ynke as other bokes ben ... all the bookes of this storye named the recule of the historyes of troyes thus enpryntid as ye here see were begonne in oon day / and also fynyshid in oon day..."