But back in the 17th century jewellery known as memento mori – ‘remember you must die’ in Latin – became very popular, worn to remind the wearer of their own mortality and the transience of life.

At Derbyshire saleroom Hansons on June 30 their jewellery, silver and fine arts sale incorporated a specialist mourning jewellery section for the first time, with 14 lots, and they plan to include another one in the autumn fine art auction on November 6.

Divine Judgment

Hansons note: “In an age where the church and the monarch desired complete authority, memento mori jewellery was used as a tool to assist the reaching of this goal. In Christianity the principle of divine judgment is prominent and the church used this to control the populace. By focusing on Heaven and Hell, salvation and punishment, it brings the concept of death into prominence.”

Such jewellery helped to cement the power of the church among a largely illiterate population, but as time went on, memento mori jewellery “became as much a statement about personal identity and self-reflection as it was a reminder of death. The wealthy and elite led the fashion, with symbolism the core principle used to reflect social and cultural values”.

The execution of Charles I in 1649 prompted the emergence of memorial jewellery under Puritan England, with loyal Royalist supporters wearing jewellery set with a secret inscription or image to mourn their dead king. Memorial jewellery differed from memento mori styles in that it commemorated a particular person.

At a time when jewellery was plain and frugal, memorial jewellery was similarly modest and unassuming with black and white enamelling leading the designs. Hansons add: “With the reign of Charles II came a freedom of self-expression and religious tolerance, challenging traditional thought. Mourning jewellery was born out of memorial jewellery and became less an emblem of religious doctrine but instead a way of publically portraying grief. Well-known events such as the Great Plague in 1665 and the Great Fire of London in 1666 left a lasting impression on society and promoted the wearing of mourning jewellery.”

In the Hansons sale a rock crystal slide mourning the death of Queen Mary in 1694 sold for a £4300 hammer price, plus 17.5% buyer’s premium (estimate £400-600). It was found by auctioneer Charles Hanson in the bottom of a box of thimbles. Made in gold and set with a compartment of the queen’s woven hair, overlaid with devices of the Royal Crown and two heavenly cherubs, and enamelled around the edge of the slide with gilt lettering, Memento Maria REGINA OBIT 22 Decembris 94. The reverse of the brooch was engraved with the MR royal cipher and simple verse, Virtue and Goodness.

Baroque influences began to permeate jewellery design during the 1680s through to the early 18th century. While the skeleton symbolism remained popular, shapes became more rectangular. The imagery of entwining acanthus flowers frequently embellished jewellery and designs were influenced by the architecture of the period.

At Hansons, a black enamelled mourning ring dated 1722 depicted the skull and crossbones within an angular bezel (the rim which encompasses and fastens a jewel) with the inscription to the black enamelled band: E.Taylor. OBT. 9.Mar 1722 AETA 80. It sold for £1500 (estimate £400-600).

The Baroque influence changed towards Rococo designs in the 1730s. Ribbon and scroll motifs, gold wirework and floral elements were very popular. By the mid-18th century the famous skull and crossbone motif had all but disappeared to be replaced with neo-classical images of a grieving widow beneath a weeping willow or beside a tomb, onto which the deceased’s initials were carved and their details engraved to the reverse of the ring head.

A George III mourning ring showing a grieving widow, plinth and urn scene, with obituary inscription for 1787, for £680 at Hansons (estimate £300-500).

Canterbury Sale

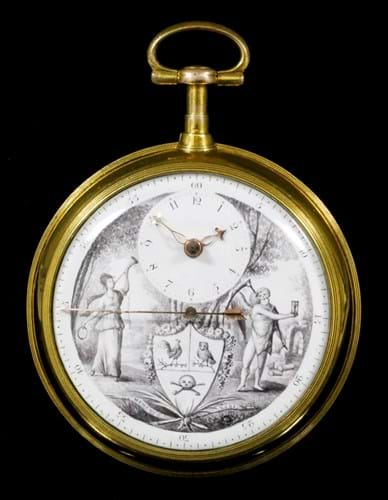

Canterbury Auction Galleries are selling a late 18th century gentleman’s gilt brass cased Memento Mori pocket watch in their August 2-3 sale estimated at £2000-3000. By George Flote of Islington, it is dated 1791. The 52mm white enamel dial is finely decorated in black with central shield pattern cartouche, decorated with a cockerel, an owl and a skull and crossbones, flanked by a standing figure of ‘Father Time’ and a trumpeting classical female.

Canterbury Auction Galleries are offering this late 18th century gentleman’s gilt brass cased memento mori pocket watch in their August 2-3 sale estimated at £2000-3000.

Symbolism remained important and urns, rivers, sheep and serpents were commonly used mourning emblems. Mourning jewellery was a way of presenting oneself in public with the trappings of grief when a loved one had died. Industries capitalised on this and with new technologies it became possible to produce mourning jewellery on a grand scale.

Queen Victoria mourned the loss of her husband Prince Albert from his death in 1861 until the end of her life, thereby re-popularising mourning jewellery. Indeed, it is often most associated with this time, when mass production made it affordable.

Whitby Jet – now a modern-day favourite of the music Goths - was propelled to eminence and pearls used to depict tears regularly adorned jewellery. While black and white enamel remained fashionable (white was often used to show the death of a child or unmarried woman), mourning jewellery saw a revival as a fashion statement and those that could afford it incorporated expensive materials into their designs.