The two handwritten letters are on offer at Chippenham Auction Rooms in Wiltshire, each estimated at £100-150.

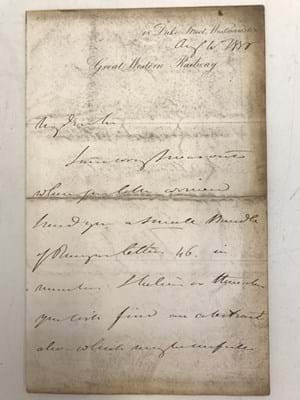

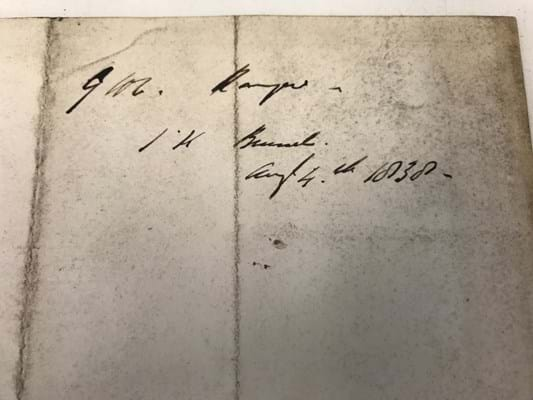

In them, Brunel writes to his engineer leading the construction of the London end of the railway to complain about a contractor working on its Reading section.

The first, dated July 30, 1838, has Brunel discussing serving notice on the contractor William Ranger and mulling over the most advantageous date. In the second dated August 1, 1838, he discusses Ranger’s acceptance of the notice. Brunel had criticised Ranger for delays in his men’s work.

Principal auctioneer Richard Edmonds said: “The reality is that Brunel was a hard-headed businessman who could be difficult to deal with. He was notorious for changing contracts and regularly under-paid his contractors. If there was a dispute, Brunel acted as both judge and jury.”

The Brunel letters are part of a private collection of railwayana, which also includes Victorian paperwork, postcards, maps and catering equipment from GWR and other lines.

The Great Western Main Line was built in order to connect Bristol, England’s then second-largest port, with London. The first section of the line – London to Maidenhead – opened in 1838. Reading was connected to London in 1840 and the entire London-Bristol stretch was open by 1841. The line passes through Chippenham, where the auction is being held.

Tunnel visions

Two black lacquer snuff boxes celebrating the opening of Brunel's Thames Tunnel which sold for a low-estimate £300 at a sale held by Matthew Barton at west London auction house 25 Blythe Road.

Despite Brunel’s undoubted genius, not everything he worked on went to plan. The broad gauge he pioneered for the first version of the Great Western railway fell by the wayside eventually in favour of the ‘standard’ gauge used elsewhere.

Another project he worked on which took a different direction was the Thames Tunnel, the world's first successfully completed tunnel under a navigable river. He worked with his father Marc, also an engineer, on this scheme.

Opened in 1843 and billed as the Eighth Wonder of the World, it quickly became a tourist attraction but it stayed pedestrian only despite being intended for horse-drawn traffic. And it wasn’t intended for tourists – cargo was supposed to be a money-spinner.

Souvenirs could be bought from the arcades below the Thames, such as the two black lacquer snuff boxes offered at a sale held by Matthew Barton at west London auction house 25 Blythe Road in November last year. They made a low-estimate £300.

The circular box cover was painted with shipping and warehouses above a cross-section of the tunnel, while the rectangular hinged lid to the other showed a longitudinal view of the twin-bore tunnel with horse-drawn traffic below shipping and the riverside.

However, the tunnel did eventually find a solid use. After 1865 it became a railway tunnel, a function it still performs today as part of London Overground.