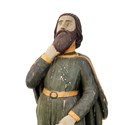

The man responsible for that was Amerigo Vespucci, the subject of a 5ft (1.5m) high (including plinth) figurehead on offer for an estimate of £5000-8000 in the May 2 sale held by Charles Miller in west London.

Well, Miller says he is not absolutely certain it is Vespucci, but given the way it is dressed, the scroll he holds and American-style boots, he is confident, and believes it would have been the “logical choice” of figurehead for an American merchantman.

Vespucci (1454-1512) is thought to have over-hyped his voyages for royal attention but it seems he went on at least four trips to the New World. According to a letter he may not have actually written, in 1497-98 his first exploration in Spanish ships sailed through the West Indies and Central America. If authentic, this means that Vespucci discovered Venezuela a year before Columbus did.

As the schoolboy rhyme reminds us, ‘in fourteen hundred and ninety-two Columbus sailed the ocean blue’. However, in 1507 French scholars were working on geography book called Cosmographiæ Introductio, and German cartographer Martin Waldseemüler, one of the authors, proposed that the newly discovered Brazilian portion of this New World be labelled America, the feminine version of the name Amerigo, after Amerigo Vespucci.

Take that, Columbus.

Decorative appeal

Miller, the maritime specialist formerly of Christie’s South Kensington, is well versed in offering figureheads at auction.

The use of a figurehead of purely decorative rather than practical value dates right to ancient times, with the Viking dragon prows or similar themes such as eyes painted on the side of Greek ships (a tradition which can be seen today on Maltese fishing boats).

The later days of these carvings is summed up by another lot estimated at £1500-2000 in the May 2 auction: King George V by renowned figurehead carver Arthur Earnest Anderson c.1930. But this 79cm (2ft 7in) carving came well after iron steamers had killed off demand for figureheads and was destined for a very different market.

Instead, the carvers found a new source of demand. Miller says: “As ships went out the next natural home was the fairground. A lot turned their hands to doing carousels and other such carvings so you find they are fantastically well done and many have marine themes - what the guys were used to doing.”

The Anderson workshop was located at Rownham Yard, Bristol, where it had been since the early 19th century, the family having migrated from Rotherhithe, London. Arthur’s father, John, was considered the finest of the wood carvers producing figureheads for sailing ships that once filled Bristol Harbour. However, by the time Arthur joined his father, the market for ships’ figureheads was nearly obsolete, so he turned his hand to carving fairground carousel figures as an alternative.

Fantastic figurehead results

Miller sold an excellent example of a male figurehead in excellent condition in November 2015 for a top-estimate £20,000. It was recovered during the attempted salvage of the Prussian brig George Forster, wrecked on the Goodwin Sands on November 30, 1856.

The half-length portrait, 4ft 2in (1.27m) high depicted Forster himself, a remarkable man who sailed on James Cook’s second voyage of discovery in 1772 as an assistant to naturalist Carl Gottfried Woide on the Resolution.

One of the highest figurehead auction results was achieved at Christie’s New York in January 2007 when a 19th century carved and polychromed wooden ship’s figurehead from the bark Edinburgh sold for a premium-inclusive $262,400 (about £134,000 at the time).

The 6ft 1in (1.85m) high design was carved in oak c.1883 by John Rogerson (1837-1925) in the form of a woman, probably Lady Edinburgh, the ship’s namesake.

In 2014, Sworders auction house in Essex sold a fascinating figurehead for £50,000, 10 times the top estimate. The carved wood and painted 2ft (63cm) high figurehead - a three-quarter length figure of a South American gaucho – decorated a Brazilian slavers’ ship captured by the Royal Navy in 1851.

Figurehead of Prussian naturalist George Forster recovered from the brig of the same name which was wrecked on the Goodwin Sands on November 30, 1856. It sold for £20,000 at Charles Miller's November 2015 auction.

The figurehead market

So, what floats the boat of figurehead collectors? “It’s a cliché, but pretty girls will always sell better than grumpy old men,” says Miller. Also, “if you have a good quality carving it is quite possible to identify the ship it came from, and if you can do that and, even better, find a black and white photograph of it from when it was on board – rare but not impossible – then it has a fabulous provenance and if the the carving is considered largely original and you are well on your way”.

What collectors don’t like is over-restoration and painting. “Paintwork that is original as possible is really what they are after,” adds Miller.

Curiously, national tastes vary. “The Americans for example prefer figureheads stripped of all paint because they like to see ‘it in the natural’ as it were, because it proves little or no restoration, whereas Brits like theirs to look like figureheads – they often prefer them to have, ideally, good sympathetic original paintwork as far as possible.”

Many figureheads are now covered in lurid colours. Miller explains: “Don’t forget the sailors themselves were responsible for what we now know as really rather gaudy carvings.”

You may sail with a figurehead of a beautiful girl, fresh from the carvers’ workshop, looking amazing, but “after a couple of voyages she is peeling and as you can’t have bare, exposed wood the sailors would just get a bucket of pink paint and touch bits up and soon your figurehead starts looking very ropy”.

When Miller sold the Forster figurehead, his catalogue included notes from figurehead historian Richard Hunter.

They read: “The world of ships’ figureheads can be divided in to roughly four main subject forms: female, male, creatures and billets-types, each one having a number of subdivisions.

“While it is no surprise that surviving female figureheads outnumber males by at least five to one, the vast majority of male figureheads are from unknown vessels, possibly depicting a forgotten vessel’s owner or local dignitary; they represent the epitome of late Georgian and early Victorian gentlemen yet, occasionally, a male figurehead survives to show that exceptions to the rule can be found, and the George Forster is one such figurehead.”

The billets-types, or billet-heads, mentioned were essentially a cheap form of figurehead – for many ship-owners figureheads were a big cost. Miller adds: “A lot of 19th century lower-grade vessels just had a billet-head, a nice little scroll, at the front, no figurehead at all, to finish the bow off.

“Figureheads were an expensive luxury: a lot of examples I’ve sold before had detachable outstretched arms which were only put on when the ship was in port. You took them out of sockets when you were at sea because they were fragile.”