The one dedicated sale was the first of the year which Leighton Gillibrand put together at Dreweatts & Bloomsbury (24% buyer’s premium).

After the March 28 sale at Donnington Priory, where 92% of the 157 lots got away to a hammer £223,000, his verdict was: “Fresh-to-market, single-owner collections of rare instruments in original condition are in high demand.”

True of antiques generally, the unspoken corollary is that material not meeting those criteria is facing a tough market.

The best, by a distance – and meriting one of Gillibrand’s scholarly 2500-word monographs in the catalogue – was a c.1660 spring pendulum timepiece engraved to the 7 x 6¾in (18 x 17cm) gilt brass dial Edward East, Londini.

The Bedfordshire-born East (1609-96) was appointed chief clockmaker to Charles II in 1660 and enjoyed the longest career in English clockmaking’s ‘Golden Period’.

This clock was very probably made within a year or two of the pendulum’s introduction into England by the Fromanteel family in 1658. Both the trains used spring barrels (rather than fusees), a feature following contemporary Dutch practice used by Fromanteel for his earliest pendulum clocks.

In a 13in (33cm) tall ebony-veneered chestnut case, it was in largely original and generally good condition. Entered from a private collection, it sold to a UK collector on the lower estimate of £50,000.

“It was an important piece and was academically appreciated by the British Museum and other horologists,” said Gillibrand. “But it lacked the long term/historic provenance demanded by the leading collectors in the field. The purchaser bought well.”

Going high above hopes was a c.1695 ebonised table clock signed to the foliate-engraved backplate by another noted maker, John Trubshaw London. The six-finned twin fusee, inside rack and bell-striking movement with quarter repeat and a verge escapement was housed in a 13½in (34cm) high case excluding the handle.

It may have started life with a gilt-metal basket superstructure with the present caddy top probably a later substitution. Other than that, and the need for clean and overhaul, the clock was in generally good and working condition. A private UK buyer took it at £17,000 against an estimate of £8000-12,000.

Longcase long faces

In contrast to these smaller clocks, longcases continue to languish.

A couple of desirable examples emerged, but at the bottom end of the D&B lots hammer prices around estimate made for salutary reading.

Examples included a 1770 mahogany-cased, eight-day clock by recorded London maker Samuel Child, at £850; a c.1770 oak-cased eight-day clock signed by Hampshire maker Willian Avenell, Arlesford, at £600 and a c.1740, 30-hour clock signed Blackburn Oakham, in an oak case and possibly a very good early marriage at £300.

A c.1695 walnut-cased clock signed to the 11in (28cm) square brass dial James Jenkins, London, was a fine piece and fared rather better.

The eight-day clock, with five-finned and latched pillar inside countwheel bell striking movement with anchor escapement, was unaltered and original.

The 6ft 7in (2m) case, with glass apertures to the sides and a herringbone-banded, quarter-veneered door with a circular brass lenticle, was in fundamentally original condition with some repairs commensurate with age.

Estimated at £4000-6000, it was a rare victory for the trade (dealers took only two of the top 10 lots), selling at £7500.

The depressed market for longcases generally appears to extend to the Continent, even for pieces by the illustrious Lepaute family.

A c.1805 gilt-brass mounted sidereal regulator, signed Henry Lepaute Paris to the 10in (26cm) circular silvered dial, had a fine movement with a Harrison’s maintaining power and pin-wheel escapement regulated by massive nine-bar ‘gridiron’ temperature-compensated pendulum.

It was housed in an elegant 6ft 9in (2.07m) case with full-height glazed front door with cast brass mouldings and a cast gilt-brass Napoleonic eagle within laurel wreath to the plinth.

Nevertheless, it went below estimate at £13,000 to a private European buyer.

The major surprises of the day were two late 19th century mahogany microscope slide cabinets. One, 15in (39cm) wide, had two glazed doors and an arrangement of 24 drawers each containing about 25 slides of geological and marine subjects. Three shallow drawers of various microphotograph slides included one titled Portraits of the Presidents of the United States, from Washington to J. Buchanan.

Estimated at £1500-2500, the c.1877 cabinet signed R&J. Beck, London sold to a collector at £10,000.

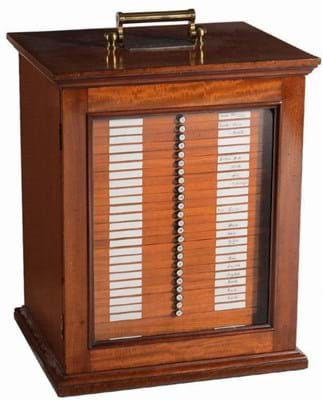

The other was unsigned and 10in (25cm) wide with a single glazed door containing 36 drawers, each with 25- 30 geological, chemical, botanical, entomological and zoological slides. Pitched at £300-500, the cabinet went at £7000.

Longcase in the lead

A longcase did lead the clocks on offer at the March 24-25 sale at Tennants (20% buyer’s premium) in Leyburn, although it was far removed from the restrained elegance of the late 17th and 18th centuries.

The 8ft 5in (2.75m) mahogany case c.1910 was elaborately carved with flowers and scrolls, a glazed door, flanked by carved floral pilasters and a plinth with a central inlaid panel depicting a basket of flowers.

The 15in (38cm) brass dial featured a seconds dial and three dials for strike/silent, chime/silent and Whittington/Westminster chime selections.

The case had some small dents and chips and the triple-weight-driven movement, chiming on eight tubular bells needed a service. However, against a £4000-5000 estimate, the clock went to a private buyer at £6000.

The other ‘striking’ feature of the day was the activity of the trade. Dealers took all three of the best-selling, highly desirable smaller clocks. An oval, brass-engraved c.1890 alarm carriage clock, 7½in (19cm) high over handle was signed W.Schonberger, Wien, and featured porcelain panels of figures in costume in woodland scenes.

It needed a clean and work on the strike and repeat, but against a £1200-1800 estimate this clock sold at £5500.

A c.1770 ebony veneered table clock signed to the dial and backplate John Kentish Junr, London also left a £1200-1800 estimate behind.

With an inverted bell top with a carrying handle, glazed side panels, pull repeat cord and front door with a brass frame border and bezel, it needed a good clean but was in full working order and sold at £4800.

The third trade buy in the upper register was a c.1870 York Minster form brass chiming skeleton clock, 22in (56cm) high on a marble base and in a glass dome, which went above hopes at £4500.