Old Master prints represent one of the last dusty corners of the art market where it is still possible to find and own an original Renaissance or Baroque work of art for under £1000.

Spend £5000 or more and a household name – Dürer, Rembrandt or Canaletto – could be within reach. Christie’s international print specialist Tim Schmelcher believes “no other field offers access to greatness for less money”.

The catch-all term ‘Old Master prints’ covers five centuries of art history.

Neatly bookended by simple medieval woodcuts and the masterful drypoints of Goya, the collecting sphere encompasses the original etchings, engravings and woodcuts made by Western artists – either by their own hand or with the aid of professional printmakers – from the 14th to the early 19th centuries.

These prints, typically distinguished from those removed from books and atlases, are not mere reproductions. As Vasari attests, major artists from Mantegna to Titian personally engaged in printmaking as both a source of income and as an artistic medium in its own right.

Naked Artistry

Prints are a chance to view an artist stripped bare and perhaps share in a moment of artistic exploration. But being a print collector can require a little imagination.

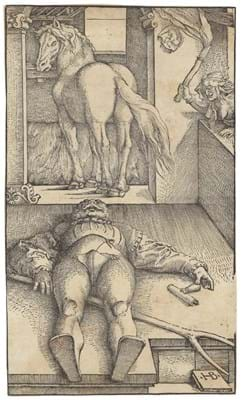

Some prints, such as the exquisite but tiny engravings of the ‘Little Master’ Hans Sebald Beham (1500-50), pack their punch in a small package while others require a level of connoisseurship before they give full reward. As fashions change there are fewer sales and specialist dealers to educate and nurture an audience.

The euphemistic invitation to “come up and see my etchings” no longer has quite the appeal today that it did in erudite Victorian society.

Doubtless the subject can be esoteric. The traditional art buying variables of artist, subject, size and provenance apply. So too, for perilously fragile 500-year-old sheets of paper, do questions of condition. However, the key determinants of price in this singular market are date of impression and printing quality. Both require judgment and experience.

Assessing a print by its age is more than good old-fashioned art historical snobbery.

The earlier the print, the closer it will be to what the artist intended. There are also, explains Schmelcher, important visual differences. “While fine early impressions give a sense of depth and atmosphere, very late impressions, taken as the ridges of a woodblock are flattened or the engraved lines in a metal plate lose their depth and sharpness, can appear one-dimensional and lifeless.”

“No other field offers access to greatness for less money”

Schmelcher cites an artist such as Lucas van Leyden (1494-1533), whose very light touch with the engraving tool meant that few strong, detailed impressions were taken before the plate began to wear and the quality declined. Place two examples of the ‘same’ print side by side and you will see what he means.

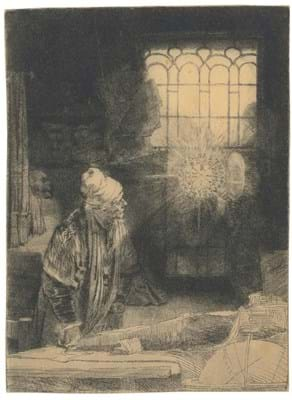

The sometimes complex subject of ‘states’ dominates the study of prints by Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn – arguably the first artist to fully explore the possibilities of the etched line.

Within his lifetime Rembrandt reworked some of his 300 or so copper plates on several occasions – adding or removing to alter mood or composition – but those same plates were ‘refreshed’ numerous times after his death. Many impressions offered today were created to satiate a growing demand for Rembrandt’s work in revolutionary France. Others are later still.

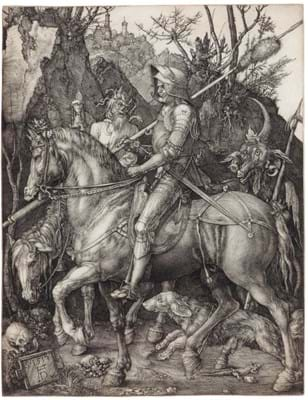

That there remains a strong market for late impressions by Rembrandt (albeit at lesser price levels) is indicative of the power of the brand. His one rival in the market is Albrecht Dürer, the towering figure of northern Renaissance printmaking.

Dürer’s engravings have been studied, copied and adored for the better part of 500 years. Most will today be catalogued with a reference to Joseph Meder whose detailed text published in 1932 did much to categorise the artist’s prints by state and sub-state.

Like Rembrandt, early versions of Dürer’s best-known prints are quite capable of commanding six-figure sums. A rich impression of the ‘meisterstiche’ Knight, Death and the Devil sold for $150,000 at Christie’s in January – although lifetime impressions of minor works can bought more reasonably.

Richard Carroll of Forum Auctions sold prints from Dürer’s Life of the Virgin series earlier this year. “Shop around and you can still buy a perfect little engraving by one of the greatest western artists that ever lived for under £5000,” he says.

Changing tastes

Much of the oxygen of publicity in the Old Master print market is reserved for Dürer, Rembrandt and Goya – the only artists who regularly rub financial shoulders with more fashionable modern and contemporary names. With ever-rising minimum lot values, auction sales in London and New York can become scripted.

As Christopher Mendez, a London specialist dealer of more than 50 years, points out, “lesser but possibly more interesting prints don’t show up simply because they fail to meet the necessary price thresholds”.

Savvy collectors are aware that, alongside the ‘big three’, contemporaries worked with near equal skill and imagination. Many were capable of conjuring images of startling beauty. Some spoke of an approaching apocalypse.

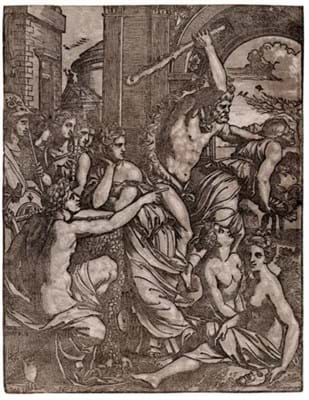

Currently the subject of a first-ever UK exhibition (at the Whitworth, Manchester, until May 28) is the Italian engraver Marcantonio Raimondi (c.1470-82-c.1534).

Marcantonio – whose copies of Dürer’s engravings and woodcuts, signature and all, were the subject of an early intellectual property law case – is best known for a groundbreaking collaboration with Raphael.

The work of his contemporary in Rome, Ugo da Carpi (c.1480-c.1532), is equally arresting: he pioneered the chiaroscuro technique using multiple blocks to build tone. German painter Georg Baselitz is one of several contemporary artists who have been drawn to this field: his collection of prints formed part of the exhibition Renaissance Impressions at the Royal Academy in 2014.

“A shift in taste favours the quirky, dramatic imagery of Mannerism”

Baselitz represents a shift in taste that favours the quirky, dramatic and sometimes uncomfortable imagery of Italian and Northern Mannerism. It has brought to the fore the work of once lesser-known printmakers such as Hans Baldung and Wolfgang Huber and furthered the cause of Hendrick Goltzius and his circle.

In short, much is down to personal taste and subject matter. Demand has fallen for the rococo visions of Watteau and Boucher, those countless bust-length portraits of 17th and 18th century faces and real or imagined Dutch and French landscapes.

Mendez, one of a handful of dealers who will show Old Masters at The London Original Print Fair this month (May 4-7 at the Royal Academy), cites the example of Wenzel Hollar (1607-77), a prolific engraver of more than 3000 etchings across a broad range of subjects. Most are priced in the low hundreds.

Among his most popular work are the panoramic Views of London produced in the wake of the Great Fire. Portraits of once worthy Stuarts “are much more difficult”.

Perhaps Old Master prints are always destined to be the art market’s best-kept secret. Schmelcher says this has long been a select market – something underlined by his recent perusal of Christie’s catalogues from the 1850s when the names of the same 10 or so buyers cropped up time and again.

But with so much energy now focused on other sectors, there has probably never been a better time to “come up and see my etchings”.