Newest victory, at the scene of past triumphs, was the Scottish Sale held by Lyon & Turnbull (25% buyer’s premium) in Edinburgh on August 16.

Top-seller among the 450 lots (78% of which sold for a hammer total of £310,000) was the wine glass by Stirling goldsmith and Jacobite soldier Patrick Murray which went to a private collector at a double-estimate £20,000 (see Pick of the Week, ATG No 2305).

The glass, credibly said to have been used by Bonnie Prince Charlie himself to toast his father James, came with a sound provenance to the powerful Bruce clan whose guest the prince had been.

In a field where repro pieces began to be produced as far back as the early 19th century – engravers added Jacobite symbols to 18th century glasses – provenance is hugely important.

That said, collectors are often prepared to back their judgment on pieces with hazier histories, as in the case of two glasses at Edinburgh.

Both with multi airtwist stems and domed feet, each was simply catalogued as a Jacobite engraved wine glass, 18th century.

One, 6½in (16.5cm) tall with a trumpet bowl engraved with rose heads and buds was estimated at £600-800 but sold at £3000.

The second, 6¾in (17.5cm) tall with a bucket bowl and similarly engraved was estimated at £800-1200 and made £4200.

Other pieces with Jacobite associations included an 18th century oil on copper miniature of Charles and a framed engraving of his time of triumph.

The 1½ x 1¼in (4 x 3cm) miniature was after Antonio David, the official painter to the Stuart court in exile in Rome. In a glazed giltwood frame, it was estimated at £2500-3500 and sold to a collector at £7000.

The signed engraving of Charles’ return to Edinburgh after the victory at Prestonpans was after Thomas Duncan’s painting but was less important than its frame.

“ In a field where repro pieces began to be made as far back as the 19th century, provenance is hugely important

The 3ft 8in x 4ft 2in (1.12 x 1.28m) frame was carved with figures of Charles, highlanders, arms and armour and shields for the MacDonalds and Macphersons.

Coming to the vendor by descent from the Macpherson family, it sold to ‘a Scottish institution’ at a top-estimate £7000.

Little piggies

A classic Scottish collecting area which has fluctuated in fashion is the output of the Fife ceramics factory Wemyss.

During the early years of the century records seemed to fall annually at Sotheby’s Gleneagles sales, culminating in 2004 when two Wemyss pigs each sold at £29,000. The record for a Wemyss cat still stands at the £20,000 achieved by L&T at the Drambuie Collection in 2006.

However, the perceived fall in demand “is only partly true”, said L&T director John Mackie.

“Certain areas like the small pigs have increased a lot since those days,” he said. “Last year a small piglet in the Apples design made a record £8500 and another made £6500. So there are areas of strength.

“Also I think the price is generally increasing for the rarer pieces and a bit flatter for the more ordinary or damaged wares.”

In the absence of high-spending Americans or British popstars (Sir Elton John was widely believed to have purchased both the £29,000 pigs), bidding at the upper levels in August was entirely done by UK, mainly English, collectors and for early material produced before the factory’s move to Bovey Tracey in 1930.

Best of the pigs was an 18in (46cm) long, c.1900 porker in the Cabbage Roses pattern, impressed Wemyss, which went well over estimate at £5500.

Top cat was a c.1900, 13in (33.5cm) tall puce-glazed sitting animal impressed Wemyss Ware/ R. H. & S. which sold within estimate at £3600.

Mackie’s point about the popularity of piglets was born out in a rather unusual way.

Two almost identical figures, each c.1900, 6¼in (16cm) long and with impressed marks, were estimated at £500-800. One in a yellow glaze sold on the lower figure. The other, in a brown glaze, made £3200.

The brown glaze was rarer, “but I think the main competition was from two collectors each trying to fill a gap in their collection,” said Mackie.

Silver stand-outs

Among the Scottish silver, the top-seller, as expected, was a set of three tureens by Alexander Edmonstone, Edinburgh 1823, with armorials of the powerful Lowlands families Douglas and Hamilton-Douglas. Weighing 176oz in all, the set went to a private buyer at a lower-estimate £12,000.

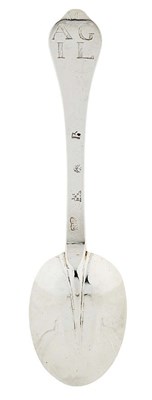

Of more specialist interest was a rare dog-nose spoon by Thomas Ker, Edinburgh 1696.

Edinburgh pieces are usually less sought-after than rarer provincial marks. However, this spoon was not only made by one of the most important smiths of the time but is one of the earliest recorded in the dog nose pattern which did not come into fashion until after 1700.

Originally from a group of three, it was similar to one sold at £3500 at L&T’s inaugural Fine Scottish Silver sale in February 2008. This August, the 7½in (19cm) long, 1.7oz spoon, estimated at £3000-5000, sold to a Scottish collector at £7500.

Provincial spoons, as usual, did make their mark. One dated c.1734, was marked IB and FB in an armorial shield for John and Francis Brown of Perth. With a deep bowl, double drop heel and beaded and engraved fleur de lys rat tail, the 8in (20cm) long spoon was estimated at £800-1200 and sold at £5200.

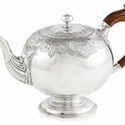

Edinburgh smiths working in the so-called golden age of Scottish silver were well represented, including James Ker, who outshone his father, the aforementioned Thomas, and became a noted and wealthy Edinburgh citizen.

Along with his son-in-law William Dempster, he made some of the most important mid-18th century Scottish plate, although here he was represented by a more minor piece, a classic bullet teapot.

Dated Edinburgh 1742, the 5¾in (14.5cm) tall, 19oz teapot sold a shade below expectations at £2300.

Scottish silver teapots are a common enough sight at auction but much rarer are silver sugar bowls, particularly those with original silver covers – hence the £6000-10,000 estimate on an example at L&T.

By Henry Bethune, Edinburgh 1725, the 3¾in (9.5cm) tall, 12.5oz bowl had an engraved crest for the Walter family and went to a Scottish collector at £8000.

While 18th century Scottish wooden tea caddies are quite common, silver ones are extremely rare. It is thought that English smiths generally supplied the Scottish trade with these expensive additions to the tea tables of the wealthy gentility.

The drum caddy pictured opposite was by William Kerr, Edinburgh 1772.

Engraved with foliate decoration, crest and motto and with its original steel key, the 3¾in (9.5cm) tall caddy went to a collector at a mid-estimate £3400.