A decade ago the US auction business was still riding the wave of the Americana boom and tasting the first fruits of the internet selling revolution. Chinese works of art were ‘the next big thing’.

But today, in President Trump’s disunited states, the art and antiques trade is facing down issues familiar to an Old World audience.

The US remains the world’s single biggest art market, generating 40% of all global sales, according to the 2017 Art Basel and UBS Art Market Report. But outside the Manhattan bubble of contemporary art and blinging jewels and wristwatches, success is hard-earned.

“The market is ever changing but there are constants,” says Karen Keane, CEO at Skinner in Boston and Marlborough, Massachusetts. “Across all disciplines, the middle and lower end has been sluggish and there is really no change there. Overall you need to sell more to stand still.”

Karen Keane of Skinner.

There have been positives from the much-documented changing focus of the international houses – the rise of minimum lot thresholds and the scaling-back in traditional sale categories.

Nine out of ten items offered to New York’s major salerooms will now be moved lower down the food chain. Some favoured firms, such as Stair Galleries in upstate New York, do well with referrals. The firm’s forthcoming sale includes the contents of a home in Nassau furnished largely through Mallett.

‘A moving target’

The migration of expertise from the centre – New York – to regional houses is just as evident in Massachusetts, New Jersey and Pennsylvania as it is in Wiltshire, Sussex and Essex in the UK.

Some experienced staff have set up on their own, adding to the growing number of professional advisory companies placing art and antiques with the auctioneers that bring the best rewards. Experience – or searching a price database – shows them that the Big Apple is not always the best place to sell. With Christie’s recent staff cuts there will surely be more of the same.

However, the accepted narrative that the focus in Manhattan is now firmly on a small number of high-revenue categories, is not one every auctioneer recognises on the ground. Few detect a consistent plan of action or sense the competitive pressures easing when a worthwhile consignment goes out to tender.

“This is a moving target,” says David Rago of Rago Auctions in Lambertville, New Jersey. “First, I hear that design departments are being downsized or abandoned, and then I hear that pricing protocols are being lowered by the very same houses.” The firm has picked up three former New York auction department heads in the past two years – although two staff members have moved in the opposite direction.

To be locked in a territorial dispute with Sotheby’s or Christie’s is seldom comfortable. Paul Roberts, president at Freeman’s in Philadelphia, says margins are squeezed because “advisers are very aware that severe auction house commission deals can be achieved on anything half way decent”.

Keane agrees. “It feels more competitive than it ever has done. Right now, I’m not sure exactly what it is the big auction houses don’t want to sell.”

It is the polarisation of the market that has brought these added pressures.

For a while finding decent Chinese works of art plugged the gap. However, Asian buyers are increasingly selective and all the low hanging fruit has been well and truly picked.

The road back will be tricky to navigate. “The US antiques market has punched above its weight, partly because of its popularity with the media. It has never really been a mass market business – even in its heyday,” says Keane. “Today, the gains are made by savings and efficiencies.”

“Demand for post-war American furniture is at an all time high

She believes the current population demographic is problematic. The Baby Boomers are now divesting. The Millennials who should be taking their place have different tastes and are saddled with the debt of a college education and the knowledge that, for most Americans, property prices are down.

And yet Wall Street is at an all–time high. “Go figure. Perhaps that’s where all the money has gone,” quips Roberts.

Paul Roberts of Freeman’s.

Americana’s slide

Across New England, Americana sales in particular remain a shadow of former glories. Lita Solis- Cohen, doyenne of art and antiques journalism on the East Coast, says “people are afraid to put things up for sale”.

As early as 2001 soothsayers were suggesting that – like the once super fashionable ‘English country house’ look – the underbelly of the previously bullet-proof Americana market might be softening. By 2008 the music began to stop.

Almost a decade on there are certainly signs of improvement, albeit at revised price levels. “I didn’t get anything. Does that mean the market is coming back?” commented one dealer after a recent sale at Northeast Auctions in New Hampshire, where 70% of the bidding went to the internet or the phone. But the feel-good factor of a market on the rise is currently absent.

“Americana had a nice incline to it for many years but there has been a precipitous drop. A $20,000 Boston desk has now become a $6000 Boston desk,” says Keane.

The fallout – what Keane calls “a race to the bottom” in terms of pricing routine goods – has been particularly tough for a dealing community already struggling to adapt to the age of the internet auction portal.

Some of the older-established names continue to hold generations of inventory, even if much of it was bought at yesterday’s prices. They are hunkering down and hope to ride it out, trading at a lower level and bargain hunting until the good times return. Others have become agents.

The new dealing model is typified by a clutch of former prominent shop owners who have a good eye, know where the rich clients are, know where many of the best items are buried and can act as middle man between seller to buyer. They carry almost no stock, so risk little ‘skin in the game’.

The Hayloft

In this environment, few salerooms can afford to offer the ‘broom clean service’ – the ‘post the keys through the letterbox on your way out’ dispersal of an entire house contents.

There is still Alderfers, situated in Hatfield, an hour from Philadelphia, holding close to 20 sales a month, some online, some in the old way of ‘have gavel will travel’. But how to make money when a 19th century chest of drawers brings $100?

“You need to sell more to stand still. A desk once worth $20,000 is now $6000

In New York, Doyle has a solution of sorts. It has launched The Hayloft, a warehouse space in the Bronx stuffed with the chattels of Upper Eastside apartments that are not deemed suitable for a catalogued sale. The merchandise is very much targeting local buyers furnishing on a budget, with the bidding conducted online akin to the eBay model.

None of the leading firms are betting the house on the online-only model – at least when selling better quality chattels. There have been some successes in niche collecting areas and the ‘footloose’ model is appealing to some ‘start-up’ firms that can set up with relative ease in the online space.

“We are disinclined to go online-only for all but the least valuable material. People intending to spend a lot of money on an object often want to see it up close, hold it, view it in context,” says Rago.

Selling to online bidders at ‘live’ sales is another issue entirely. Typical sell-through rates hover at around 20-30% with most of the major firms listing on multiple platforms – including Bidsquare of which Rago and Skinner, were founder members with Brunk Auctions, Cowan’s, Leslie Hindman and Pook & Pook.

It gives them a little more control at a time when both bidder fees (now 5% at Invaluable.com) and the sheer mass of content are rising.

An internet portal recently boasted via a sales pitch of adding more than 200 new names to its established roster of clients. “Who on earth are they?” says one seasoned auctioneer. “I’ve worked in the business for 40 years and I don’t know 200 fine art auctioneers.”

Bricks and mortar

For the established names, town centre saleroom buildings remain an important statement of brand and an environment that encourages both spending and consigning.

“The bricks and mortar component remains essential,” says Rago. “When we stage a major sale, our building is a beautiful place to walk through and enjoy the art. Maybe we do it as much for ourselves as we do our clients, each sale being the culmination of four to six months of work.”

Skinner typically hold online-only sales alongside catalogue events. Together with the neatly displayed objects of a calibre that make a journey to Boston worthwhile, are the backroom tables of other material that will be offered to virtual bidders.

They have been performing well enough but by themselves are not a game changer.

Keane recently conducted an illuminating analysis of the two different ways of selling.

“We ran some data on this, comparing how an object performs when sold in a catalogue sale or in an online-only sale. We found no great difference in the selling rates or in the relationship between hammer price and estimate.

“It does make you ask the question. There are more eyeballs than ever looking at this stuff coming up for sale. Why then is it not bringing more money?”

On a related topic – one perhaps germane to Sotheby’s recent decision to drop buyer’s premium for online-only sales (ATG No 2306) – Skinner conducted an experimental sale of another kind in spring 2016. At the request of a consignor – a long standing opponent of the buyer’s premium – the firm conducted a ‘no premium’ single-owner sale.

The consignor believed hammer prices would be significantly higher as a result. “But did it bring 23% more? I can’t say that it did,” Keane says. “It seems the market rules. It is very hard to move the needle.”

Market strengths

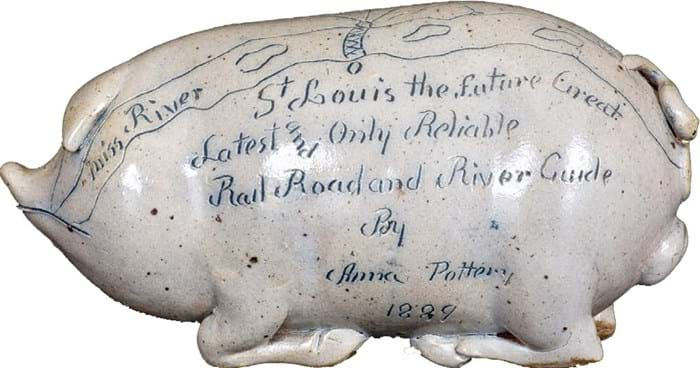

Encouragingly, pockets of trade remain stable. Southern decorative arts – Virginian furniture, Edgefield pottery jars and the like – have generally fared better than those from New England.

Likewise, the ‘mud babies’ of the great Biloxi, Mississippi potter George Ohr continue to shine in the subset of American art pottery – with good reason. They are, says Rago, an “anomaly resulting from the interest of fine art buyers and European collectors, who don’t necessarily share a similar passion for most other ceramics of the period”.

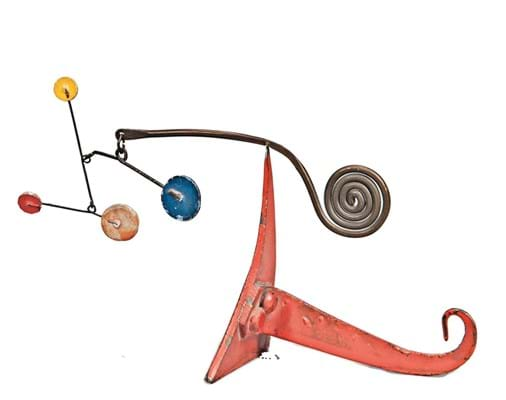

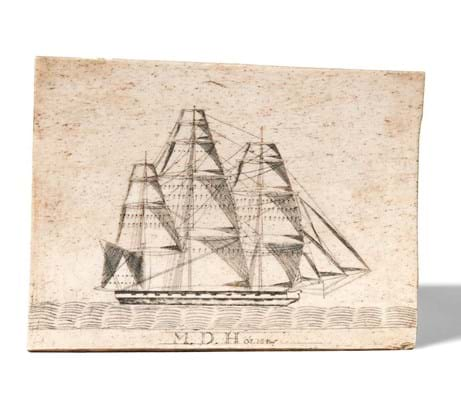

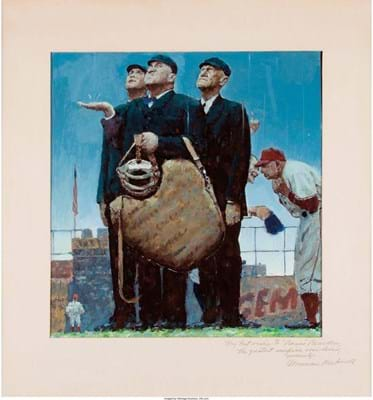

As always, there’s no problem selling the occasional ace. Exceptional objects, such as those illustrated on these pages, still turn up and when they do, they are bringing as much as ever.

“There are still what we call ‘bluebirds’. But bluebirds are not a business model,” says Keane.

Modern design is a success story – proof that this is a story of changing fashion as much as economic blight.

Rago says “the demand for post-war American furniture is at an all-time high” with the stock of both Paul Evans and George Nakashima continuing to rise.

Reflecting market confidence in Nakashima as a seminal figure in the history of American Studio Craft, Rago offered 15 pieces on September 24 while Freeman’s October 8 design sale is anchored by a private collection of over 20 lots. In the strong global market for precious stones, jewellery too has grown in importance.

“There are opportunities. If only I was 20 years younger

As the energy in fine art sales moves from the traditional to the modern and contemporary, interesting things are happening. While some markets, such as the New Hope School – otherwise known as the Pennsylvania Impressionists where Freeman’s have a good track record – are maturing, scores of artists from the 50s-70s are subject to reappraisal.

There are large gaps in museum collections when it comes to Jewish and black American art and a whole range of regional painters and sculptors that operated alongside (but usually outside) the Ab Ex or Pop art movements. These gaps are gradually being filled.

Telling a good story can also go a long way to reviving even the most challenging parts of the antiques trade. The market will receive a boost when Sotheby’s disperses 2000 lots from the home of David Rockefeller in the spring.

Freeman’s too has enjoyed success selling single-owner collections and invested heavily in people and marketing in this area. Sales this year conducted for Kip Forbes, Andre and Nancy Brewster of Maryland, Jeffrey M Kaplan and last week’s Patricia and John Roche collection were all, at their respective levels, outstanding events.

In a market where the collecting zeitgeist has shifted, it has also paid not to put all the eggs in one basket. Design and 20th century dec arts specialists Rago Auctions became a full-service auction house about 15 years ago. “We had the space, the experts were available guns-for-hire, and we knew how to produce an auction,” says Rago.

“Beyond that, the ‘new’ departments brought us fresh and different knowledge and a larger client base, much of which has crossed over in purchasing our more typical offerings. We grew from a $20m company about a decade ago to a $33m company today.”

Cowans in Cincinnati, beginning in the niche market of historic Americana, has followed suit while Heritage, still dubbed a specialist in coins, sporting memorabilia and comics in some quarters, now offers sales across the board. Morphy’s in Denver, Pennsylvania has assumed control of a number of niche operations in fields such as toys, mechanical music, antique firearms and jewellery.

Leslie Hindman is building a series of regional outposts away from its Chicago headquarters, the latest opening in Georgia.

All are evidence that the market in a cyclical low does present real scope for those prepared to play a longer game.

Roberts, who as vice-chairman of Lyon & Turnbull benefits from a transatlantic perspective, agrees. “In a downturn there is always a world of opportunity for those willing to take advantage. If only I was 20 years’ younger,” he quips.