Hostilities had largely closed down much innovation in the furnishing industry, with the Government Utility scheme strictly regulating production and materials.

After the 1939-45 conflict, one of the main difficulties faced by manufacturers was the shortage of raw materials. Resourceful designers with an eye to what was happening in the US turned to materials such as aluminium, plywood and synthetics to fill the gap.

Like the equivalent pieces emerging on the Continent, the resulting designs were lighter, airier and completely different, drawing inspiration from industrial processes and making use of mass production methods.

Official recognitions

There were official efforts to improve things and provide a showcase for these new designs and the fledgling fresh industrial shoots. The Britain Can Make It exhibition, organised by the Council for Industrial Design, was a key feature in drawing public attention to this new look and drew crowds to the Victoria and Albert Museum where it was staged in 1946.

Even better known is the Festival of Britain of 1951. A raft of names from architects to artists and designers showcased their talents at this event, be it in terms of public furnishings for the festival or the scientific-inspired spikey graphic wallpapers, fabric and lighting designed by the Festival Pattern Group, many of which were on show in the Regatta restaurant. These new designs captured the imagination of a public keen for change.

Many of the works on show at these events are now seen as icons of British mid-century design: pieces such as Ernest Race’s Antelope chairs, Robin Day’s furniture for the Festival Hall, the fabrics designed by his wife Lucienne or Jessie Tait’s distinctive patterning on Roy Midwinter’s newly fashionable US-inspired Stylecraft tablewares.

Vintage status

What was then termed the ‘Contemporary’ look has now gained vintage status and attracts interest at all levels, from collectors focusing on the innovations of key designers to enthusiasts looking to furnish their homes in what is now retro-fashionable style.

Plenty of material is available at all price points to satisfy both types of buyer on a regular basis, from dealers at fairs and shops to auctions around the country.

As in any field, provenance and originality play a role in determining values, but in general terms many of these pieces, even those by well-known names, tend to be more affordable than the examples produced by their Continental counterparts.

Pictured here are some of the most recognisable illustrations of the British mid-century look – a mix of pieces that have already sold or are coming up for sale.

Ernest Race

This pair of wool-upholstered DA2 chairs, a Race design of 1949 used at the Festival of Britain, were purchased by the vendor’s family at a sale held at the end of the exhibition. They were hammered down for £1600 in Mallams’ auction on December 7, 2017.

Race is famously known in his early career for his use of unconventional industrial materials and techniques, plywood and – when timber was in short supply after the war – surplus aluminium and steel.

Race’s firm was run with JW Noel Jordan. Like the Days and others, he gained exposure from his work at the Festival of Britain, for which he designed his Antelope and Springbok seating which could be used indoors and outdoors and featured across the festival site.

He also designed ranges of upholstered and wood furniture, although his company moved increasingly into the contract market from the 1960s. A Race Furniture company still exists.

Robert Heritage

This cabinet designed in 1954 for GW Evans was offered for sale by Woolley & Wallis in October 2017. It measures 3ft (92cm) high and is fitted with printed sliding doors and drawers. The cabinet sold with an extra cabinet storage unit for a hammer price of £1800.

Heritage had a long career as a furniture designer working for a number of different British firms, including GW Evans, Archie Shine and Gordon Russell.

A key feature of his work is the distinctive use he made of exotic veneers and restrainedly sophisticated detailing such as turning and stamping.

One other classic Heritage production was the cabinet furniture that he designed for the firm of GW Evans. This made use of graphic architectural friezes designed by his wife Dorothy, which were screen printed onto pale-coloured woods.

Ercol

This 1960s Ercol 442 recliner and ottoman with blue upholstered seats and backs sold for £1200 at Sworders in October 2017.

Ercol furniture is one of the few firms from the post-war period that is still in production today. Lucian Ercolani founded Ercol in the 1920s but it came to popular prominence in the aftermath of the war.

Ercolani trained in High Wycombe, home of the vernacular furniture trade and in particular the Windsor chair. He took this hand-made tradition and mechanised the production, and post-war he gave it a modern twist which was showcased at the Britain Can Make It exhibition and the Festival of Britain.

Unlike a lot of other furniture innovators working at this time, the distinguishing feature of Ercol furniture was its reliance on solid timber (notably beech and elm). Ercolani’s tables, chairs and his upholstered pieces were very popular and as a consequence produced in large numbers.

In the past couple of decades there has been a revival of interest in early post-war designs from what had by the late 20th century become a traditional staple of British furnishing. Some of the firm’s current designs are based on its mid-century classics.

The volume and long production of Ercol means there is a good deal of this furniture around today on the secondary market in auctions and on sites such as eBay, especially dining sets and occasional tables. This keeps much of the material very affordable but, as always, more unusual, scarcer pieces command a premium.

Poole Pottery

Poole, a pottery whose origins went back to the 1870s, was one company that actively embraced the new contemporary style and the hunger for bright colours and striking repeat patterns.

Like most British potteries, it had to work in the climate of heavy restrictions on decoration in the immediate aftermath of the war, limits which only gradually relaxed.

AB Read, Ruth Pavely and Guy Sydenham were key figures in this new-look pottery which morphed into an American and Scandinavian-inspired range of asymmetrical, curvilinear-shaped designs termed Freeform and was produced from the mid-1950s.

Robin and Lucienne Day

The husband-and-wife partnership of Robin and Lucienne Day spans decades but both first came to prominence in the immediate post-war years: Robin for his furniture designs and Lucienne with her textile designs.

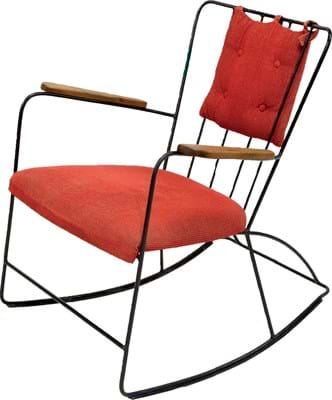

Robin won a low-cost furniture competition in New York with a cabinet he designed with in conjunction with Clive Latimer. This led to his ‘big break’, a commission to design the furnishings for the Festival Hall just at the point when the Festival of Britain was taking off. This meant that the maximum number of people saw his trademark chairs with their strong but thin metal legs and preformed seats.

Robin went on to forge a successful partnership with the furniture manufacturer Hille and Sons. As well as contemporary products for the domestic market, he worked on a large number of contract lines for Hille.

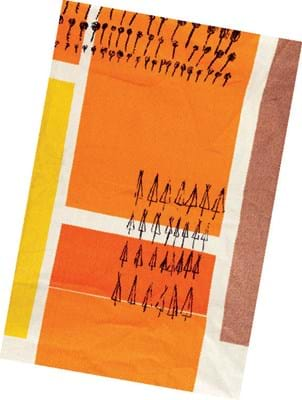

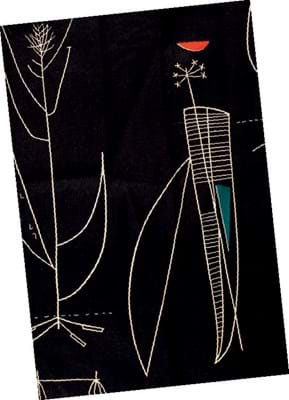

Lucienne too came to prominence in the Festival of Britain era. Her fabrics were used in the Homes and Gardens Pavilion, where especially her innovative Calyx pattern met with wide acclaim.

She designed fabrics for a number of manufacturers, some of which were retailed by Heal’s. They are notable for their linear take on botanical structures or even purely abstract designs.

Robin’s designs for Hille were often produced in substantial numbers and come fairly readily to market, while it is lengths of Lucienne’s furnishing fabrics, many of which remained popular for a considerable time, that tend to appear these days.