Stuart Devlin’s (1931-2018) final design project was a book – a self-titled hardback that, through relatively few words but copious images, will serve as a worthy memorial to a designer-craftsman who helped change the look of English silver forever.

Stuart Devlin: Designer, Goldsmith and Silversmith was published just a few months before Devlin died in April this year, aged 86.

Remarkably, given his status as the gold standard for British post-war silver, relatively little had been published on Devlin’s oeuvre. The handful of exhibition catalogues and the chapter in Designer British Silver, co-authored by Pearson Collection curator John Andrew and Hungerford dealer Derek Styles in 2014, is about it.

Andrew believes the new book and the moment of reflection that comes with Devlin’s passing will contribute towards “a wholesale reappraisal” of his work.

None other than the Duke of Edinburgh concurs: in a brief foreword to the book Prince Philip describes Devlin as “probably the most original and creative goldsmith and silversmith of his time, and one of the greats of all time”.

A parcel gilt caddy spoon, London 1975 – £320 at Tennants, Leyburn, April 2018.

Market effect

The market will be watching. After warming up in the early 21st century, prices have not moved a great deal in the past decade.

Alongside British adherents are a handful of Dutch and American buyers and keen followers in Devlin’s native Australia where, as the designer of the national coinage, his name is well known.

However, Andrew – an evangelist for the minigolden age of British silversmithing – maintains the field remains something of a “best-kept secret”.

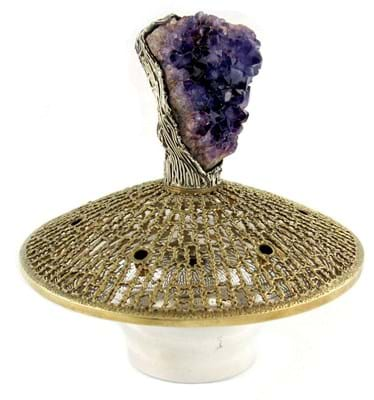

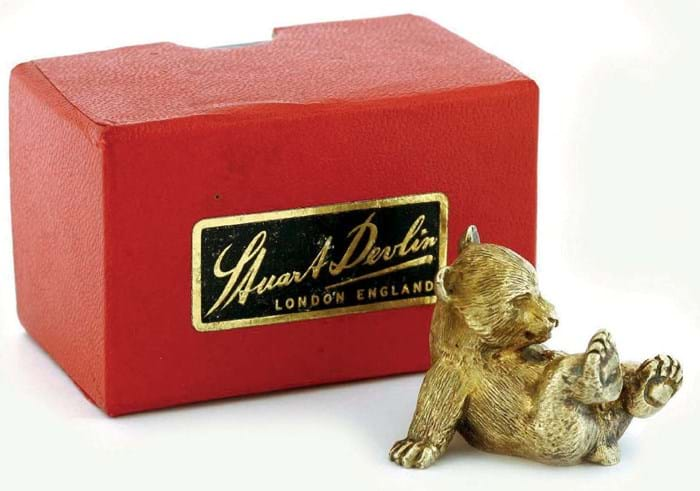

The entry level to the Devlin market is provided by the kitschy gold and silver ‘surprise’ Easter eggs and Christmas boxes or animal paperweights made in the 1970s-80s in the Fabergé tradition.

They remain popular collectables in the £200-500 bracket, although the occasional rarity will bring more. At Christie’s New York in June 2017, an egg made to mark the centennial of the Metropolitan Opera c.1983 (it opened to reveal a miniature crystal and glass chandelier) sold at $2200 (£1650).

However, although at one time employing more than 60 staff in something akin to mass production, Devlin was far more than a maker of luxury gifts and trinkets.

“Some people who know about contemporary and modern silver still look upon Stuart Devlin as a manufacturer and tend to dismiss him accordingly,” says Andrew.

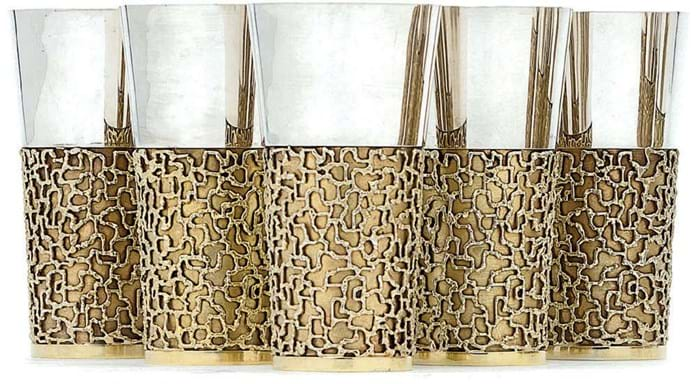

A set of 12 parcel gilt silver beakers, London 1968, 105oz – $13,000 (£10,000) at Sotheby’s New York, April 2018.

Devlin early days

The book sheds light on his early and later commission work. A revelation is a five-piece teaset raised from sheet metal by Devlin as a precocious 13-year-old – the silversmithing equivalent, says Andrew, of “Mozart producing his first symphony at the age of eight”.

Equally captivating are the wares made while Devlin was studying at the Royal College of Art.

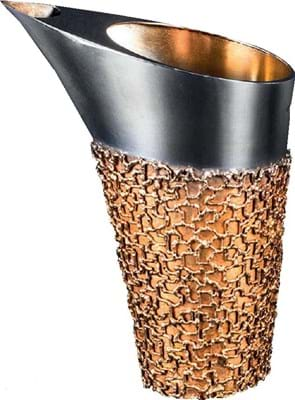

Best known are the tall handleless coffee and café au lait jugs made with deep nylon sleeves. Only one of these was created by Devlin himself (acquired at the time by the Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths), but others were made on licence by the firm of Wakely and Wheeler in 1960.

A pair (the property of the Marquess of Lothian) took £7800 at Sotheby’s Olympia in May 2003 and another sold for £7700 at Christie’s in November 2009.

A recent addition to the Pearson collection, bought from a silver dealer, is one of three brandy warmers with wooden handles and stands made c.1959. Kept by Devlin for some years before they were given as gifts, they were not sent for assay until the mid 1960s.

Like his contemporary Gerald Benney (1930- 2008), Devlin soon became disenchanted with the prevailing taste for Scandinavian design. Instead, he preferred what he described as “richness and romanticism” and “pieces that added delight, surprise, intrigue and even amusement to what had become austere and even sterile”.

Though a pioneer of modern-day goldsmithing techniques (from 1970 his filigree forms were achieved using an acetylene torch), Devlin returned some of the old-fashioned pomp and grandeur to the dinner table. A 34-light 707oz candelabrum made for the Duke of Westminster in 1976 was typical. Sold at Christie’s in June 2007, at £38,000 it still holds the record price for Devlin on the secondary market.

Relatively little of this ilk has been seen at auction in the past couple of years.

Among the highest prices of recent times was a 50oz parcel gilt champagne bucket (1972) sold for £10,500 at the Gerrards auction in Lytham St Annes in May 2015.

Andrew points to private sales of a pair of threelight candelabrum with handmade filigree globe shades (around £15,000) and a near-complete dinner service sold by Styles Silver on behalf of a Continental owner.

However, with such items the exception rather than the rule, he asks the question: “Where are many of these pieces now?”

The great unknown is just how much of Devlin’s output fell victim to the Bunker Hunt bullion spike of 1979-80 when – on the cusp of changing fashion – scrap silver touched $50 an ounce. Could Devlin’s surviving major work be much scarcer than we think?

A selection of recent auction prices for Stuart Devlin silver is shown with this article.

A Stuart Devlin silver gilt bear cub paperweight, London 1976, in original box – £480 at Sworders, Stansted Mountfitchet, June 2018.

Stuart Devlin timeline

1931 Born in Geelong, Victoria, the son of a painter and decorator and a housemaid.

1955 Leaves his job as an art teacher in the small town of Wangaratta to study gold and silversmithing at the Royal Melbourne Technical College.

1958 Studies at the Royal College of Art (1958-60) followed by two years at Columbia University, New York. Goldsmiths Hall buys much of his student work.

1963 Wins a competition to design the first decimal coinage for Australia. Devlin would subsequently design coins, medals and insignia for more than 40 other countries.

1965 Returns to London and opens a small workshop in Clerkenwell.

1972 After three years with Collingwood of Mayfair, he opens his own gallery on the ground floor of a workshop employing up to 60 people.

1979 Opens his own retail premises in Conduit Street after striking a deal with his patron, the Duke of Westminster.

1980 The collapse of the silver price in the 1980s leads to the closure of Devlin’s shop. He later focuses on private commissions based in West Sussex.

1983 A retrospective titled 25 Years of Stuart Devlin in London is held at Goldsmiths Hall.

1983 Having weathered the global recession of the 1980s and the attempted cornering and collapse of the silver bullion market, he moves his showroom back to Clerkenwell. A retrospective titled 25 Years of Stuart Devlin in London is held at Goldsmiths’ Hall.

1987 Devlin’s Champagne Diamond Exibition at Goldsmiths’ attracts so many visitors, people queue up to four hours. The collection includes 180 pieces of jewellery set with white, yellow, cognac and champagne-coloured diamonds and three automated eggs. The Carousel Egg set with more than 3600 diamonds is snapped up before the opening by Prince Jeffri of Brunei.

1989 The London operation is closed and the Devlins move to West Sussex where he concentrates on many private commissions.

1996 Devlin is Prime Warden of the Goldsmiths’ Company.

2000 Millennium commissions include the spectacular Millenium Dish for the Goldsmiths Company.

2012 The Goldsmiths’ Centre opens combining workshops, training facilities and exhibition space. Devlin was a driving force behind its creation and despite ill health, he was able to teach the first course to graduate designers.

Source: Stuart Devlin: Designer, Goldsmith and Silversmith.

The Stuart Devlin book published just before he died - Stuart Devlin: Designer, Goldsmith and Silversmith.