“It seems the common wisdom – that clock cases followed developments in the furniture trade – is wrong. It was in fact furniture that was influenced by clocks.” In researching a forthcoming exhibition of Golden Age clocks, Richard Garnier, former head of Christie’s clock and watch department, came to an intriguing conclusion.

In late 17th century England, at least, clock cases and the materials used to make them set the fashion that cabinetmakers followed. The reason why? Because “these new mechanical timepieces were the ultimate in designer technology”.

The exhibition Innovation and Collaboration at Bonhams Bond Street from September 3-14 spotlights the period c.1650-90 – an era when the tumult of politics was mirrored by the white heat of scientific development.

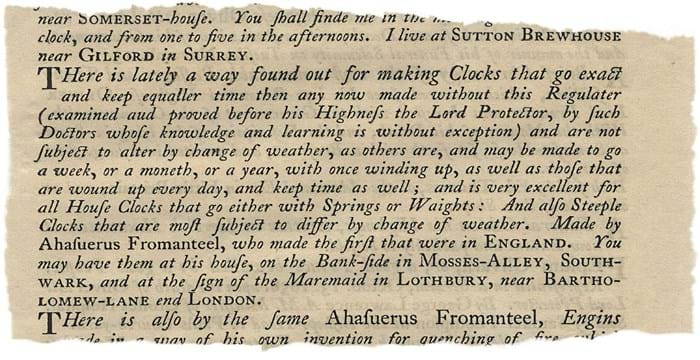

Among the exhibits is a copy of the Commonwealth Mercury from November 25, 1658 that includes Ahasuerus Fromanteel’s famous advertisement for ‘Clocks that go exact and keep equaller time’. With these printed words, the English domestic pendulum clock was born.

The display of more than 100 17th century timekeepers includes loans from the Science Museum, the Clockmakers Company and the collection of George St Vincent, 5th Lord Harris at Belmont House in Faversham.

However, most are from two complementary private collections: an anonymous lender and the Isle of Man entrepreneur and horologist Dr John C Taylor (b.1936). Both view the exhibition, which includes free guided tours, as an opportunity to “share their passion with the public and to ignite a new interest in clocks”.

Taylor, best known for inventing the bi-metallic thermostat used by every electric kettle, was the subject of a profile in ATG No 2231 (March 12, 2016). He has, beginning in the mid-1970s, amassed one of the great collections of early English clocks.

His rich cache of stellar material is evidence that – with so many eyes turned to ‘sexier’ collecting disciplines – recent decades have been a mini-golden age for a handful of committed horology collectors.

Fromanteel’s genius

Among all the pioneering English clockmakers working the shadow of civil war, Taylor admires Fromanteel in particular. The innovations made at Moses Alley, Southwark, and The Sign of the Mermaid in Lothbury were numerous.

Taylor adheres to the theory that the Fromanteel workshop may have made pendulum clocks in London as early as 1655 (two years before breakthroughs in Holland) – perhaps selling one to Oliver Cromwell for £300.

“Nobody really knows what that clock was but… he [Fromanteel] refers to it as having the new regulator in it,” says Taylor.

On view will be three of the half a dozen surviving Fromanteel box clocks from the late 1650s and a quartet of marginally later striking table clocks c.1660-65 housed in much more elaborate cases. These clocks – an area of the market that has come under considerable scrutiny in recent years with the uncovering of forgeries – will be displayed alongside each other to allow for comparison and the highlighting of both similar and contrasting features.

An Ahasuerus Fromanteel and Edward East cubic full grande sonnerie gilt table clock, 1640. Coming from the Taylor collection, it will be one of the highlights from the ‘Innovation and Collaboration’ exhibition at Bonhams from September 3-14.

Working in Westminster from c.1662-70, Samuel Knibb (1625-74) is thought to have enjoyed a close association with Fromanteel, although just five clocks bearing his name are known to exist. Courtesy of both private collectors and a well-known clock from the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers, all five will be exhibited at Bonhams, including the previously unrecorded table clock c.1665 that surfaced at the saleroom in 2013 and sold for £457,250.

Proof of Garnier’s observation, its ebony veneered architectural case appears remarkably prescient for the third quarter of the 17th century.

Royal patronage

Patronage and the role of the post-Restoration economic boom in the creation of highly accurate timepieces of great mechanical complication before the close of the century is among the themes explored by the exhibition.

One of the highlights of the Taylor collection from the later period, and the item he told ATG he would rescue first in the event of a fire, is the so-called Selby Lowndes Tompion – an ebony and gilt-brass mounted grande sonnerie table clock once owned by William III’s secretary to the treasury, William Lowndes.

Across his career Thomas Tompion made just 13 grande sonnerie clocks, each striking both the quarter and the hour every 15 minutes (or 4992 chimes a week). This one, numbered 215, c.1692, with a Roman general finial, is thought to honour the victory at the Battle of the Boyne.

What would be its market value? Remarkably there is a recent precedent. The Medici Tompion, a similar clock c.1696 presented by William III as a diplomatic gift to Cosimo de Medici, was sold by Lewes dealer Anthony Woodburn at Grosvenor House in 2007 when the asking price was in the region of £2.25m.

Re-offered by Carter Marsh as part of the Tom Scott collection when ticketed at £4.5m, it won the Object of the Year award at Masterpiece in 2015 when its sale to an American collector was rubber stamped.