In total more than a ton of handset Venetian-style metal type – including all punches and matrices – ended up in the watery depths. As he wrote later in his diary, he was “bequeathing to the river” every reminder of a highpoint of modern typography.

Cobden-Sanderson had been one half of Doves Press – a sometimes volatile venture sited close to The Dove pub in Hammersmith that is key to the story of the private press ‘movement’. The metal type he discarded on its closure, seemingly unable to countenance its reuse elsewhere, was the iconic Doves Type developed 17 years earlier with his bitterly estranged business partner Sir Emery Walker (1851-1933).

Many pioneers of private press, such as Cobden-Sanderson, were rooted in Arts & Crafts idealism: a desire to return publishing to its medieval roots and away from the ‘cheap’ mechanisation of the Industrial Revolution.

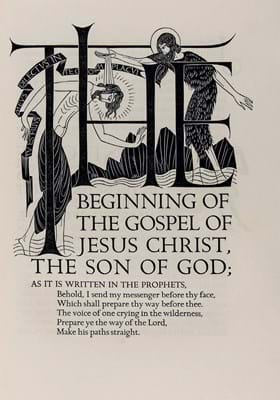

A magic-lantern lecture titled Letterpress Printing and Illustration given by Walker to the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society in 1888 is credited with inspiring William Morris to rent a cottage near Kelmscott House in Hammersmith and set up three traditional printing presses. Between 1891- 98 the Kelmscott Press would produce 53 different editions – over 18,000 volumes in total.

Among them is perhaps the finest book of the Victorian era, The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer with a Morris font modelled on 15th century incunabula and wood engravings by his long-term collaborator Edward Burne-Jones. Copies priced from £20 each were sent to subscribers in May 1896, shortly before Morris died.

“A trophy book coveted by a wide range of magpie collectors and investors”

Today, as a trophy book coveted by a wide range of magpie collectors and investors, a standard copy on Batchelor handmade paper might begin at £50,000 – although other Kelmscott books of lesselevated status are much more affordable. More obscure titles, printed in smaller runs of 200-300 each, can be found at between £1000-10,000.

The £16,000 bid at Forum Auctions in March 2016 for an Apple paper printing of the eight-volume The Earthly Paradise of 1896-97 was an exceptional price.

The customer base

With its focus on materials, typefaces, page layout, illustrations and bindings, Kelmscott defined the parameters and principles of British private press – re-awakening the relationship between art and books at a time when the printed page was at a nadir.

It demonstrated too the existence of a potential customer base among the wealthy industrialists and left-leaning middle-class intellectuals that populated a plethora of Victorian book and manuscript collecting societies.

The ventures that followed in the 20th century, both in Britain and abroad where Arts & Crafts ideas resonated with near equal measure, were to be Morris’ legacy.

The Ashendene Press was founded by Charles Harold St John Hornby (a partner of WH Smith) in Chelsea in 1895. New fonts were cast and artisans such as Edward Johnston, Graily Hewitt and Eric Gill employed to produce books for sale through a subscription service.

St John Hornby’s interest – fostered by both Emery Walker and Sydney Cockerell (a major collector of Kelmscott Press books) – was primarily artistic: “I have worked for my own pleasure and amusement without having to keep too strict an eye upon the cost,” he said when writing to Cockerell in the last months of his life.

The folio-sized Tutte le opere di Dante Alighieri of 1909 limited to 111 copies (105 on paper) was the firm’s most ambitious undertaking and its masterpiece. A copy sold at Christie’s in 2013 for £35,000.

However, as London dealer Sophie Schneideman wrote in the introduction to the catalogue of Ashendenes owned by Clarence B Hanson Jr (1908-83) of Birmingham, Alabama, “amongst all this grandeur there were still some wonderful jewels produced in small numbers, often with hand-drawn coloured initials by Graily Hewitt.

“The most obvious gems are the Lucretius, the Virgil and some smaller books produced just for family and friends such as the Story Without an End and the Oscar Wilde Tales.”

Cobden-Sanderson had joined with Walker to found the Doves Press in 1900.

His mission statement – based on an address given to the Art Worker’s Guild in 1892 – was titled The Ideal Book or Book Beautiful. A Tract on Calligraphy Printing and Illustration…

It began: “If the Book Beautiful may be beautiful by virtue of its writing or printing, or illustration, or binding, or by virtue only of the thing to be communicated to the mind, it may also be beautiful by the union of all to the production of one composite whole.”

Doves books (the full set comprises 40 books and nine minor pieces) would have no illustrations or ornament other than the occasional hand-painted initial.

Instead, wrote Roderick Cave in The Private Press (1983), they “depended for their beauty almost entirely on the clarity of the type, the excellence of the layout, and the perfection of the presswork”.

Although undoubtedly an acquired taste – something reflected in the currently relatively modest prices for many Doves Press books – the five-volume 1903 Bible is considered one of the pillars of any representative private press collection. The last copy sold at auction, offered by Forum Auctions in January, sold at £7000.

The collecting spectrum

Collectors in this wide-ranging field cover an equally broad spectrum: those whose primary impetus is text and typography (private press books often forming part of a wider whole that might include much earlier books and incunabula), those attracted by the binders’ art or those with a focus on illustration.

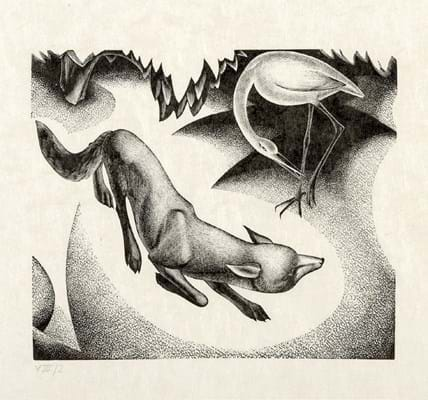

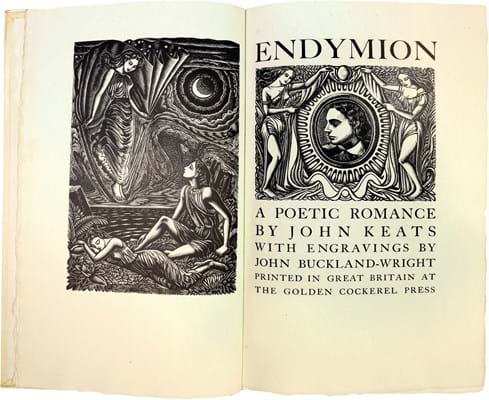

The inter-war period ushered in something of a golden age of English wood engraving. The black-line engravings drawn from medieval sources of the earlier presses are in stark contrast to the modernist designs of the Golden Cockerel press under the aegis of Irish artist and author Robert Gibbings or the books produced by the Guild of St Joseph and St Dominic commune in Ditchling, Sussex.

The work of the 1920s and ‘30s is rightly celebrated. Between 1930-33, two of Britain’s most technically gifted and imaginative wood-engravers – Blair Hughes Stanton and Agnes Miller Parker – worked at Gregynog. The press had been established a decade earlier by the sisters and art patrons Margaret and Gwendoline Davies near Newtown in Powys. Herbert John Hodgson oversaw the operation of a platen printing press while George Fisher ran an in-house bindery.

Catering to a niche with typical print runs under 300 (some much smaller), this was also the era of the very special edition. Many were specifically designed – as St John Hornby called it – simply to create “good sport for collectors”.

Books came with the option of custom bindings or illustrations.

For example, accompanying the 1926 Golden Cockerel printing of The Procreant Hymn by E Powys Mathers with five illustrations by Eric Gill was the offer to more open-minded subscribers of a series of alternative plates.

These far racier versions, with both male and female figures presented in a state of greater realism, raised the very real prospect of prosecution for obscenity. The main defence of the press was that it was a private press, not a bookseller. The original plates appeared for sale at Bloomsbury Auctions in 2009 selling at a surprise £10,000.

In a similar vein the 25-volume Dickensian issued by Nonesuch Press in 1937, each bound in different coloured coloured cloth, was sold with one of the copper illustration plates from the original Victorian printing.

In a similar vein the 25-volume Dickensian issued by Nonesuch Press in 1937, each bound in different coloured coloured cloth, was sold with one of the copper illustration plates from the original Victorian printing.

With its small but dedicated audience, the market for private press books can enjoy such moments of rude health. “After a brief lull private press works have certainly picked up in the last 10 years,” says Rupert Powell at Forum Auctions. “Right now it is rocking.”

The Modern British art boom is an important driver – admirers of Gill, Eric Ravilious and Paul and John Nash have been quick to discover their prowess in print – but it is also possible to view the current buoyancy as a response to the white heat of technological change.

Roddy Newlands of Shapero Rare Books in Mayfair sees it like this: “In this era of dogged digitisation and the demise of the printed word, there does seem to be an increasing respect and demand for high-quality, often traditional bookmaking practices.

“Typography, illustration, paper-making and binding are all elements which, when brought together in happy union, can result in something wondrous both to behold and hold.”

Schneideman says the electronic word processor with its wealth of different typefaces and font families has renewed awareness. “There is an increased interest in typography and design because, rather than handwriting or the typewriter, we all create our work on computers.”

Nonetheless, some of the old rules apply. Powell says condition is key.

“Unlike a modern first that was thumbed before it became a classic, these books have generally been looked after by people who love books. The buyers too are perfectionists so copies that are not in good condition are difficult to sell. But the best copies are bringing ever-stronger prices.”

The end and the beginning

Few of the first and second generation private presses survived the recession of the 1930s or the onset of war. In 1933 Golden Cockerel was sold and became a publishing house. Ashendene closed in 1935 and Gregynog in 1940.

However, the core ideals of private press were to prove long-lasting.

They were the impetus behind the high standards of book design and typography that have become the norm in commercial publishing – and many modern ventures that continue to emphasise individuality through format, illustration and bindings.

“The use of computers has increased interest in typography”

As well as works from the major houses of the pre-war period – and perhaps the associated genre of livres d’artiste – many specialist dealers will carry creations by modern British printers such as the Old School, Whittington and the reborn Gregynog presses.

Schneideman, who deals in private press books of all types, says the field of contemporary private press books is mushrooming. “In many ways there is too much focus on the high spots of this area – the blue-chip items that have become investment objects.

“More interesting is what is happening elsewhere. There is a thriving culture of artist books – driven by artists themselves rather than authors or idealists. It is all about the book as an object.”

However, among those keen to keep the ideals of the earlier movement alive is Robert Green, a self-confessed Doves Press obsessive who spent three years creating a digital facsimile of the ‘lost’ Doves type.

In 2014, assisted by professional divers, he uncovered close to 150 pieces of the original 16 point metal type close to Hammersmith Bridge.

Some pieces have been ‘returned’ to the Emery Walker Trust.