Antiquities and ancient art – legal issues in a changing trade

Regardless of whether an object is considered an antiquity, an object with known archaeological significance, or a piece of ancient art, an object created in antiquity without a known history, or an object with other national, cultural or diasporic significance, in recent decades, the pendulum has swung making the landscape harder to navigate for collectors and dealers.

Small dealers and auction houses are reportedly facing a rising number of challenges when dealing in objects coming to the market that have been removed from their country of origin, even if they were removed legitimately or are not subject to restrictions.

For example, as reported in ATG (No 2408), East Sussex auction house Burstow & Hewett recently withdrew a rare Maori cloak after it received intimidating messages from disgruntled social media users, despite being under no apparent obligation to withdraw the lot.

Larger auction houses have also faced difficulties in recent years involving multi-million-pound lots that were sold amid protests from national governments.

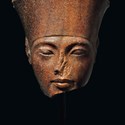

For example, the Republic of Turkey in connection with the sale of the ‘Guennol Stargazer’ in 2017. Or, more recently, Egypt with respect to the sale of a quartzite statue of King Tutankhamen in July of this year. In both, cases the lots were offered at Christie’s.

In many cases, the legal landscape is unclear, with a hodge-podge of conflicting laws dictating what a dealer or collector should or should not do in the face of challenge.

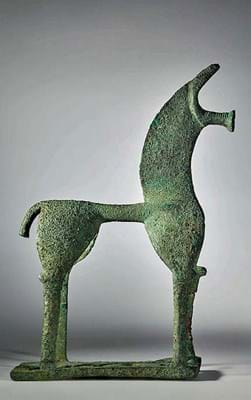

The ‘Guennol Stargazer’, an Anatolian marble idol from the Chalcolithic period c.3000-2200 BC hammered for $12.5m (£9.7m) at Christie’s New York on April 2017, although the sale was not concluded.

A more regulated world

Source countries have put pressure on the trade through national and international law, and a framework of treaties.

The first international treaty to specifically deal with antiquities removed from a source nation was the Protocol to the Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict of 1954 – the Hague Convention.

Intended to address the movement of objects during the Second World War, it dealt specifically with the disintegration of culture caused by war and conflict.

What followed was the UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property, adopted in 1970. The Convention was intended to apply to cultural artefacts stolen from institutions, such as museums, or culturally significant sites, such as religious monuments.

The UNESCO Convention requires national signatories to implement their own laws to enable its provisions. It created a clear delineation between source nations and market nations, and the roles and responsibilities of each.

These Conventions do not apply retrospectively and only nations (rather than individuals) have a cause of action against other nations if they have also implemented the relevant Convention. It is up to individuals to decide how to comply with the Conventions themselves, subject to certain national laws that are in place.

What is the state of play?

Various nations have their own laws dealing with the preservation of their cultural heritage.

Taking two examples, Turkey and Egypt, both have earlier laws governing the movement of cultural property that have been superseded.

Turkey enacted a piece of blanket legislation in 1984 stating any cultural and natural properties requiring protection that are known to exist or may be discovered in the future qualify as state property.

Egypt, another source nation, also enacted a similar law in 1983 banning the sales of all antiquities originating from the country. Laws such as these have caused claims to be made in market nations to seek the return of items deemed to be national property.

However, there can be disconnect between the laws of one nation and another on the one hand, and public and private laws on the other.

Market nations have implemented private rules concerning the dealing of objects, but will only generally respect national laws of other countries, such as those mentioned above to the extent claims are made in respect of objects that left the source nation post-1970, when the UNESCO Convention came into force (or for certain nations after the date they became a party to the Convention, which may be later) or if it can be proven that an object left a country illegally, according to the laws of that country.

With many antiquities, it can be very difficult to trace how they left the source country, as there may not be records available. The story may be slightly different for pieces coming from monuments if it can be proven an object came from a designated monument, as many countries have earlier laws dealing with specific monuments. A case by case assessment must be made.

Another way governments influence the trade of antiquities is through their import and export laws.

For example, earlier this year the EU adopted a new EU Regulation affecting import of cultural goods into the EU. The legislation, although not yet in force, intends to stop the import into the EU of cultural goods which have not been lawfully exported from their country of creation or discovery. Very vulnerable cultural goods (such as archaeological objects and elements of monuments) which are more than 250 years old will require an import licence issued by the EU member state to which they are being imported. Less vulnerable cultural goods (including paintings, sculptures and books) more than 200 years old and worth at least €18,000 will require an import statement to be provided by the importer.

In the EU, at least, this regulation will reach further back than the UNESCO Convention, creating a higher due diligence burden for those seeking to bring objects into the EU to establish the legality of export from a source nation.

Practical points for the trade – due diligence and how to respond to claims

Anyone involved in the antiquities market must look carefully at who is selling an object, their reputation, the physical object and its provenance and the nature of the transaction.

Checking export and import certificates and databases for stolen objects such as the Art Loss Register, Interpol or the International Council of Museums’ Red Lists, are also measures for due diligence.

Objects lacking in documentation supporting their legal status, such as evidence of its ownership history, where it came from, and how and when it was imported or exported, should be treated with extreme caution.

Due diligence is very object specific and will depend on the level of information that is either publicly available or that has been recorded in relation to the object in question.

For example, an auction catalogue entry may reference books, academic journals or the records of collections. The object itself may provide clues to the trained eye, so expert appraisals may assist establish the authenticity of an item.

If a dealer or auction house receives a compliant about an object, it should thoroughly investigate and verify the provenance information it has been provided.

There may be a valid reason for the complaint, so, if required, advice should be sought on whether the claim has any merit from a legal standpoint and, if so, how the complaint should be handled. As with the example of the Maori cloak above, cases may not be contested or reach court, as pressure or moral arguments may result in one party backing down.

For the trade, the key is assessing whether a potential claimant has a strong or weak claim before taking any decisions.