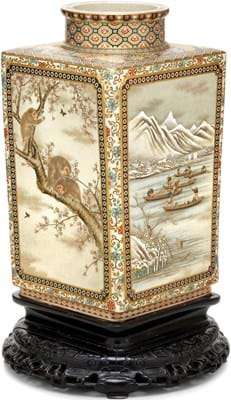

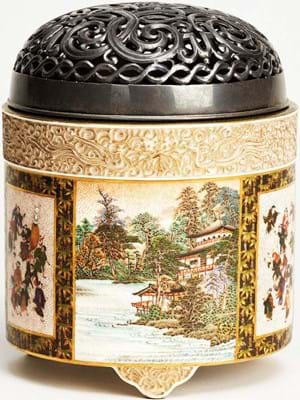

Meticulous execution, a jewel-like palette and the symbols and vignettes of the mystical East. In the Western imagination, at least, the distinctive enamelled and gilded earthenwares known simply as ‘Satsuma’ have come to epitomise Japanese ceramics.

And Satsuma did have its roots in old Japan and the Edo (1603-1868) period. Kilns producing functional earthenwares from a dark iron-rich clay had operated in this part of southern Kyushu since a team of Korean potters was forcefully brought here in the 17th century.

However, nishikide Satsuma, the product that forms the basis of most ‘Satsuma’ collections today, was very much the result of a culture clash of the 19th century.

The West’s early exposure to Satsuma had been at the 1867 Paris Exposition Universelle. It was the first major display of Japanese arts and crafts in Europe (after influential smaller shows in London in 1851 and 1862) and the beginning of a collecting craze and the phenomenon that was Japonism.

The South Kensington Museum (which became the Victoria and Albert in 1899) bought several pieces. From this moment almost all ceramics production in the Satsuma prefecture would be geared towards foreign exports.

Unlike lukewarm China, ‘new’ Japan took its participation in the international exhibitions very seriously.

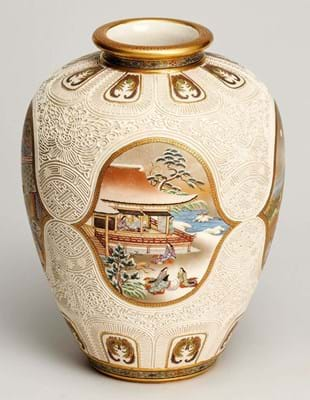

As the Meiji government declared itself open for business, success in Paris was followed by Vienna in 1873. The Illustrated London News wrote of the latter event: “In the centre of the galleries is the porcelain comprising some beautiful specimens of the so-called Satsuma ware, the characteristics of which are a soft ivory glaze, with minute waving lines and admirably realistic flowers.”

At the Centennial Expo in Philadelphia in 1876 Japan took 30,000 objects and spent $600,000 on its display – by far the largest sum of any of the 30 participating nations. It certainly had the desired effect. Japan-a-mania arrived in North America.

To Western connoisseurs these early Satsuma wares, often simple floral patterns placed in ‘negative’ space, were exotic and sophisticated. But exactly what they believed they were buying is debatable.

Spurious history

Somehow by 1875, when George Ashdown Audsley and James Lord Bowes published the pioneering Keramic Art of Japan, ‘Satsuma Faience’ had acquired a curious and totally spurious history that dated back two and a half centuries.

In 1879 excitement greeted the emergence in London of an ‘ancient’ cache of Satsuma vessels described as ‘The Papal Pieces’. They were stated to have been ‘prepared for the Jesuit priests’ expedition from Japan to the Holy City in 1582’.

The myth of ‘old satsuma’ and its implausible chronology persisted well into the 20th century.

A highlight of Sir Herbert and Lady Ingram’s honeymoon in Japan in 1908 had been ‘The great Satsuma day’. With the aid of a dealer who ran a curio shop in Miyanoshita, near Mount Fuji, Sir Herbert had finally concluded the negotiations to acquire a collection of a ‘retired sumo wrestler’ in Tokyo.

Writing in the 1930s for Connoisseur magazine, Lady Ingram later described specimens that were ‘exceedingly scarce…practically all made for the prince’s court’. Truthfully, most were 30 years old at the very most. It had been a tourist trap.

Japan was content to allow its new-found clientele to ‘discover’ its native products – many of which were hybrids carefully tailored to Western taste. The Satsuma that appeared for sale at the world’s fairs in the last quarter of the 19th century required imported technology (liquid gold was a recent invention of the Meissen factory) and employed subject matter that chimed with the target market.

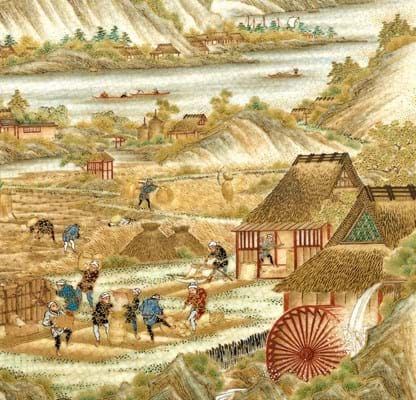

Later Satsuma wares were made in the knowledge that Edo and Meiji period woodblock prints and printed books were being collected in huge numbers in the West, where translations of old Japanese tales of heroes-in-exile, perilous journeys and star-crossed lovers had become essential reading.

Western ideals

Satsuma reflected Western ideals and quickly ceased to be a geographical marker. Etsuke factories sprung up across Japan. Some decorating workshops in Kobe and Yokohama specialised in painting blanks that had been fired and glazed in Satsuma province. Other studios made their own pots, eliminating any connection with the Satsuma region.

The English designer and committed Japoniste Dr Christopher Dresser wrote in 1882 that ’99 out of 100 cases’ of the ‘Satsuma’ that arrived in Britain turned out to be made in the Awataguchi district of Kyoto.

Much to the ire of critics, quality and novelty was often sacrificed in favour of mass production.

In his travelogue penned in Japan from 1877-83, Edward Samuel Morse lamented the workmanship of a pile ’em high, sell ’em cheap etsuke he visited in Yokohama.

“Previous to the demands of the foreigner, members of the immediate family were leisurely engaged in producing pottery reserved in form and decoration. Now the whole compound is given over to feverish activity of work, with every Tom, Dick and Harry and their children slapping it out by the gross. The haste and roughness of the work confirms to the Japanese that they are dealing with people whose tastes are barbaric.”

Collectors today, typically interested in only the best 1% of Satsuma production, will sympathise.

Best moments

Fortunately, it was not simply a race to the bottom. There were artisans and studios that continued to produce fine, high-quality pieces both throughout the Meiji and into the Taisho period.

It is these that provide the market with its liveliest moments today at price points that range from the eminently affordable entry level (tolerable pieces are available well under £500) to its masterpieces (£20,000-plus).

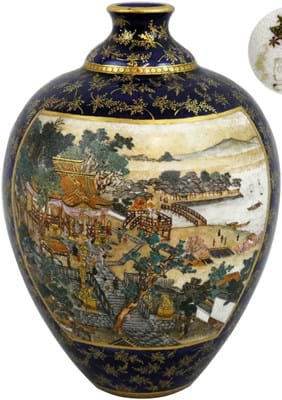

Two of the best-known studios, capable of the near-perfect execution, minute detail and stylistic brilliance that enthusiasts look for, were those of Kinkozan Sobei and Yabu Meizan.

The scion of a Kyoto dynasty of potters patronised by the shogunate for six generations, Kinkozan Sobei VI (1824-84) had successfully replaced the custom he lost following the Meiji Restoration with the burgeoning foreign trade. The studio that he passed on to his son Kinkozan Sōbei VII (1868-1927) was both the largest producer of Kyo-Satsuma and the maker of some of the finest quality Satsuma items.

Exhibitions in Barcelona (1888) were followed by those in Paris (1889 and 1900), Chicago (1893), St Louis (1904) plus several of the Naikoku Kangyo Hakurankai (domestic industrial exhibitions) in Japan itself.

The decorating workshop of Yabu Meizan (1853-1934), established in Osaka in 1880, produced perhaps the finest of all Satsuma ware.

Throughout his career he specialised in ‘old style’ figural scenes – battles, processions and festivities that used copper templates to achieve sometimes remarkable detail – but is equally admired today for the much more open ‘contemporary’ style that emerged in the 20th century.

He too focused his energies on the international expositions, visiting each venue, playing a major organisational role and frequently winning prizes.

Global reach

The pieces intended for display at these influential global events are among the greatest and most desirable of all Satsuma wares. A large square-sided vase by Yabu Meizan sold for $165,000 (£124,000) at Bonhams New York in September 2017.

Both Kinkozan and Yabu Meizan were participants in the last and largest hurrah for the golden age of the Satsuma style: the Japan-British Exhibition held in the White City area of London in 1910.

Among those who bought works from both stands was Lt Col Kenneth Dingwall (1869-1946), an avid collector of Asian works of art and founding member of the Oriental Ceramic Society. Shortly after the event he presented his purchases to the V&A, adding to a collection that had begun in Paris 43 years before.