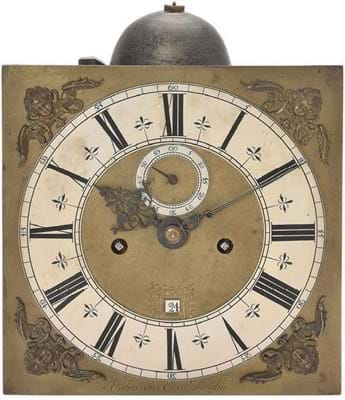

Out of fashion longcases may be, but the c.1685 ebonised eight-day example offered in Newbury on June 24 was in fine condition with a sophisticated eight-day movement in a 6ft 3in (1.9m) tall panelled case. It was engraved to the 10in (25cm) square dial with the signature Edwardus East Londini.

Edward East (1602-96) had the longest and among the most lucrative careers of any of the great names of the Golden Age of English clockmaking, working for several monarchs and during the Interregnum. Made a freeman of the Goldsmiths Company in 1627, he was appointed as one of the first assistants of the Clockmakers Company in 1632 and – as a Royalist – was to become clockmaker to Charles II in 1660.

His career spanned some enormous leaps in technology. East was 54 when Christiaan Huygens first used a used a pendulum for a weight-driven clock in 1656 and 68 when William Clement produced what is credited with being the first longcase.

Dreweatts’ clock, made during the reign of James II when East was in his 80s, included the latest refinements of the age such as bolt-and-shutter maintaining power and a strike train with internal locking integral with the rim of the great wheel. As with most lots in the catalogue, it was the subject of a small essay by Dreweatts specialist Leighton Gillibrand – a long-time practice which today looks custom-made for intenet bidders.

It sold online to a private collector right on mid-estimate at £50,000.

Wonderful Watson

Overall, the day ended with 84% of the 191 lots finding buyers and a hammer total of £322,660.

Most of the higher bids came from collectors, including the above-estimate £14,000 on a rare quarter-repeating ebony table timepiece signed to the backplate Samuel Watson, London.

Watson’s wealthy client list attests to his talents: he made two complex astronomical clocks for Isaac Newton and another for Charles II. This clock would have resided in a household that could afford at least two state-of-the-art timekeepers. With silent-pull quarter-repeat mechanisms sounding the hours and quarters on two bells only on demand, it was designed to allow for an unbroken sleep in the bedchamber.

The day’s third five-figure star was a rare miniature ebony table clock with strike/silent selection and calendar aperture to the 4in (10cm) gilt-brass break-arch dial which was signed Henry Fish, London. Fish worked at the Royal Exchange from 1736-74.

It was a project: the 9in (23cm) tall break-arch case had some losses to the ebony veneer and the original pull-quarter repeat mechanism had been removed from a movement that had been converted from a verge to an anchor escapement. Nonetheless, it doubled the mid-estimate selling to a specialist dealer at £13,000.

French ticks

French clocks played a major role among the 19th century offerings.

Leading the field was a c.1870 gilt brass oval grande-sonnerie striking calendar carriage clock stamped to the backplate with Paris maker Pierre Drocourt’s oval trademark and indistinctly inscribed to the dial for the retailer Tiffany, Paris. In good overall condition – the 6in (15cm) high gilt bronze case had very little wear – it doubled the lower estimate in selling to a collector at £8000.

A saleroom favourite was an 11in (28cm) gilt brass singing bird automaton clock. It was engraved to the movement for Japy Freres Et Cie, Exposition, 1855 Grande,Med., D’honneur and stamped and inscribed H’y Marc, Paris for Henry Marc, the early 19th century maker whose business by this point was mainly as a retailer. A small number of these Oiseaux Chantant automata were produced during the 1860s-70s – including an example sold in Geneva by Antiquorum eight years ago for around $40,000.

Dreweatts’ example, which required restoration to release the bird on the hour and repair its two-note call, went to a Dutch buyer online at a mid-estimate £7500.

Noted dynasty

The skills of the noted horologist dynasty Fournier of Paris and Grenoble and of leading Paris bronzeur and gilder Claude Galle were combined in one of the sale’s most eye-grabbing items: the 10in (25cm) tall ormolu and patinated bronze Empire mantel clock in the form of teapot.

Signed Fournier h’ger, a Grenoble to the dial, the clock’s eight-day movement required work but was in good original condition, as was the case. One of the few top pieces to go to the specialist trade, it sold within estimate at £6500.

English 19th century horology was best represented by the more austere excellence of chronometers by two dominant names of the period.

One, dated 1815, was signed to the backplate Barrauds Cornhill London 750, the firm which supplied the Royal Navy for 75 years. Incorporating Harrison’s maintaining power and Earnshaw-type spring detent escapement, the movement had some mid-19th century replacements as to be expected from a long-service naval chronometer. Housed in its 6in (15cm) wide, brass-bound three-tier mahogany box, it doubled the lower estimate in selling at £5000.

A second chronometer, c.1840, was inscribed to the 3½in (8cm) diameter silvered dial Charles Frodsham, 7 Pavement, Finsbury Park, London, No. 2012 and to the mahogany and brass box Arnold, Charles Frodsham, 84 Strand, London.

Gillibrand deduced that, as Frodsham (1810-71) acquired the business of the late maker John Roger Arnold in 1843, here he was using up old stock from his former Finsbury address and Arnold’s former business. It doubled the upper estimate, making £7000 online.