This year marks the 150th anniversary of the death of the greatest English novelist of the 19th century – and accordingly more than one and a half centuries of a vibrant collecting market.

The writings of Charles John Huffam Dickens (February 7, 1812-June 9, 1870) were the target of bibliophiles during his lifetime.

According to Adam Douglas, senior specialist at the Peter Harrington dealership, Dickens was already seriously collected, in much the way modern firsts are today, well before the contents of his library at Gad’s Hill Place, Kent were dispersed in 1878.

The buying audience was then, as it remains today, chiefly in the UK and US. “The market took an uptick around the time of the Dickens birth centenary in 1912 and the publication of John C Eckel’s The First Editions of the Writings of Charles Dickens (1913) that gave collectors a finder’s list of the must-have editions,” says Douglas.

“This was the time Comte Alain de Suzannet (1882-1950) began to collect – the major buyer of Dickens until 1950 and the donor of many important items to Dickens House.”

Wall Street Crash

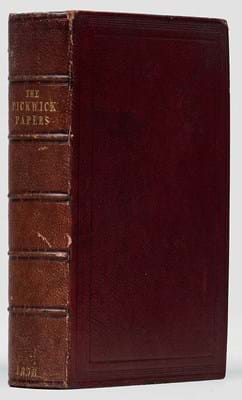

Huge prices for Dickens material were achieved in the 1920s prior to the Wall Street Crash. “The Jerome Kern copy of Pickwick Papers in parts brought $28,000 at auction in 1929. Merely adjusted for inflation, that would be nearly $420,000 now,” says Douglas.

The fact that Dickens’ literary reputation took a hit in the mid-20th century did not overly concern the market. The public never deserted its favourite.

Douglas adds: “FR Leavis famously excluded Dickens when writing [his book of literary criticism] The Great Tradition (1948), which did affect Dickens’ standing among academics. But Leavis’ influence has waned. Dickens stayed popular and his reputation shows no signs of diminishing. He is a towering figure sui generis.”

The key targets for today’s serious Dickensians are presentation copies, first-issue copies and complete sets of the pioneering serialised copies that became the dominant mode for publishing Victorian novels.

Douglas adds that one area worthy of further exploration is the publisher’s deluxe bindings, which were sold on publication date at a higher price than the cloth case-bindings. “These are not well described in the standard bibliographies, with the result that the relative priorities of these states are unknown. Even so, it is evident that they are far scarcer than cloth-bound copies.”

“It’s something that Dickens would have hated, because he resented American publishers making money without paying for his copyright

Self and Drizen

Two major Dickens collections have been dispersed at auction in recent years: the collection of American TV producer William Self (1921-2010) at Christie’s New York in 2008 and that formed by London chartered accountant Lawrence Drizen sold by Sotheby’s in 2019.

Both included exceptional prices for well-preserved first issues and inscribed copies. The Self library (incorporating a stellar collection inherited from Kenyon Starling in 1983) included one of the earliest-known presentation copies of A Christmas Carol, inscribed and presented to Mrs Eliza Touchet on December 17, 1843 – two days before the official publication date. It still holds the auction record for a Dickens novel, selling at $290,500.

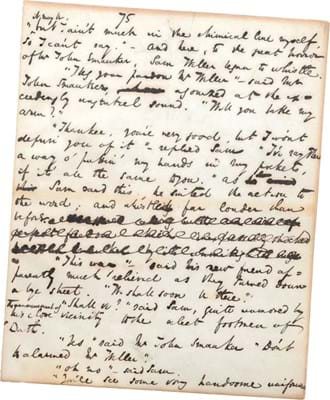

Manuscripts of Dickens’ works are much rarer to commerce – the Alain de Suzannet sale in 1971 was the last occasion on which a significant group of leaves was sold – although currently Peter Harrington has one of only five leaves from the original Pickwick manuscript in private hands priced at £97,500. It was formerly in the Starling collection.

More accessible are elements of Dickens’ famously voluminous correspondence. Most now reside in archives and libraries, but missives on topics from character research to philanthropy do appear for sale.

There are other more modestly priced areas of the Dickens market that Douglas considers worthy of collecting. “The entry level for most collectors are still the original first editions of the major novels in demy octavo book form, which can be found relatively easily in contemporary bindings. A new area for some collectors are the American editions, even though they were not authorised. It’s something that Dickens would have hated, because he resented American publishers making money without paying for his copyright, but these editions [the subject of a separate bibliography by Walter E Smith in 2012] are increasingly collected."

“The English language editions published in Germany by Tauchnitz are another inexpensive branch of collecting. Dickens had a good relationship with them and authorised their publication for the continent.”

A selection of prices for a wide range of Dickensiana appears in this section of ATG's Books, Maps & Prints Supplement 2020.

The Ragged School

As perhaps the best-known social critic and reformer of his day, Dickens was solicited for influence and financial help across a range of good causes.

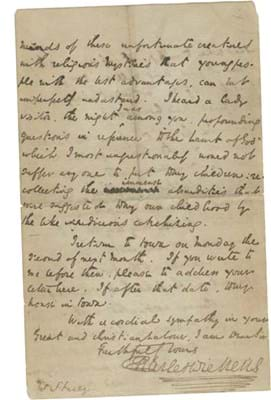

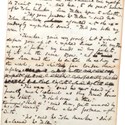

In this letter, dated September 24, 1843, Dickens writes to Samuel Robert Starey, secretary of the newly-founded Ragged School in the Field Lane neighbourhood of London – the squalid area chosen as the site for Fagin’s den in Oliver Twist and the inspiration for A Christmas Carol.

Across four pages Dickens offers his help in the venture but (as he disapproved of evangelicalism) asks that Starey keep an eye on the religious impulses of those visiting the school.

He writes: “Would you see any objection to expressly limiting Visitors... to confining their questions and instructions, as a point of honour, to the broad truths taught in the School...

I set great store by this question, because it seems to me of vital importance that no persons, however well intentioned, should perplex the minds of these unfortunate creatures with religious Mysteries...”

Dickens wrote an article about the Field Lane Ragged School while the editor of Daily News for just 10 weeks in 1846.

Sold at: Bonhams, London December 2019, £6500 + 25% buyer’s premium

A miserly request

“Will you go to Mr Edmunds at Willis’s, and ask him if he has, or can at once get me, Merryweather’s Lives of Misers? I have present and particular occasion to refer to that book, or any other, or others containing accounts of Dancer, Elwes, and other misers well known.”

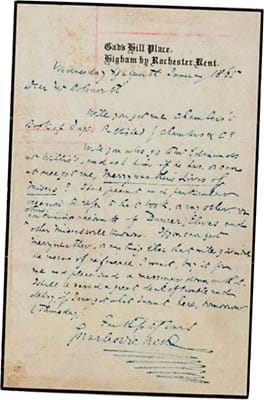

In this letter, dated Gad’s Hill Place, Rochester, Kent, 11th January 1865, Dickens is researching miserly behaviour to develop the character of Nicodemus Boffin in his final novel Our Mutual Friend (1864-65).

Sold at: Forum Auctions, April 2019, £1200 + 25% buyer’s premium

Don’t miss the next instalment

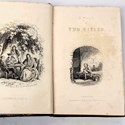

Serialised fiction surged in popularity during the Victorian era, due to a combination of the rise of literacy, technological advances in printing, and improved economics of distribution.

Dickens, who used cliff-hanger endings to keep readers in suspense, helped establish the viability and appeal of the genre and most novels henceforth first appeared as instalments in monthly or weekly periodicals.

Dating from the point where Dickens’ career took off, one of the scarcest of his works is the original parts issue of Sketches by Boz. These had originally appeared in magazines and daily newspapers, with a few being gathered into book form in 183637, before Chapman & Hall, enjoying great success with The Pickwick Papers (the final instalments0 sold 40,000 copies), bought the copyright and produced a parts issue in 1837-39. This copy is from the Lawrence Drizen collection.

Sold at: Sotheby’s, London, September 2019, £50,000 + 25% buyer’s premium

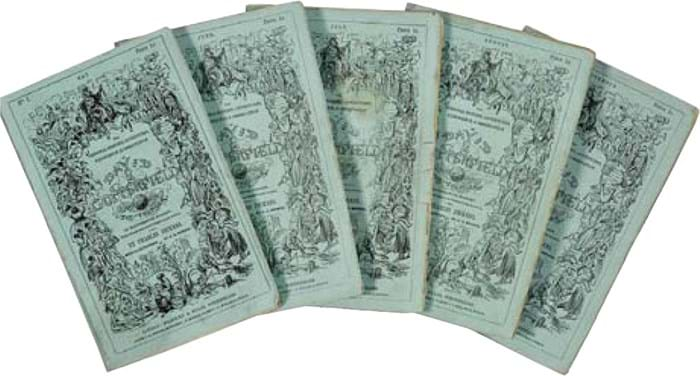

Copperfield in parts

The 20 parts of The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences, & Observation of David Copperfield were published by Bradbury & Evans from May 1849 to November 1850. By the time of this work – Dickens’ eighth and favourite novel – more complete sets were sold and kept together.

This copy was offered in the original blue pictorial wrappers with replaced backstrips.

Sold at: Bonhams New York, December 2019, $3500 (£2800) + 25% buyer’s premium

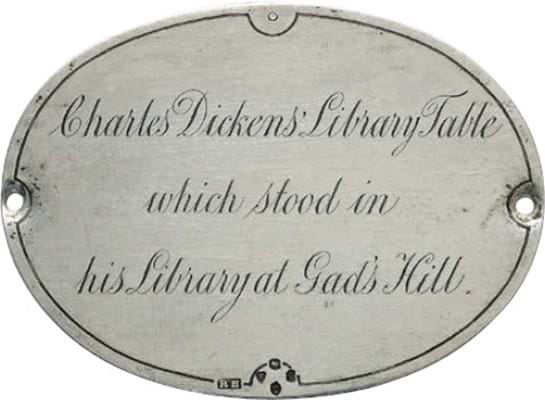

Furnishing Gad’s Hill

This William IV revolving drum table, c.1835, was used by Dickens during most of his career – first in his London home at Devonshire Terrace; then his offices on Wellington Street where he published Household Words and All the Year Round; and finally in his library at Gad’s Hill Place in Higham, Kent.

On one occasion, when he was abroad, Dickens precisely described this table and its position in his library so that a friend could locate a set of keys in one of its drawers.

One of the very first objects to have been formally labelled with Dickens’ name (a drawer is set with the silver plaque, pictured above right), it is thought that the table was bequeathed to Dickens’ eldest son Charley before it was acquired by his younger brother Sir Henry Fielding Dickens at the contents sale of Gad’s Hill Place in 1878.

His descendants offered it for sale with an estimate of £800012,000 in 2017.

Perhaps the best-known pieces of furniture from the library at Gad’s Hill Place are the writing desk and chair on which Dickens wrote some of his later classics.

Donated by the Dickens family to Great Ormond Street Hospital in 1870, they were sold together for £433,250 at Christie’s in 2008 and then purchased by The National Heritage Memorial Fund in 2015 for just over £780,000. Desk and chair are now on display at the Charles Dickens Museum.

Sold at Christie’s SK, December 2017, £52,000 + 25% buyer’s premium

Legal issues

This Spode porcelain part dessert service, c.1825, comes with a Dickens connection. It was owned by John Farquhar Fraser (1790-1862), the lawyer who defended the £1.5m interminable intestate case of his uncle John Farquhar (1751-1826), gunpowder magnate and owner of the Fonthill estate.

Dickens, who in 1827 had taken a job as a legal recording clerk, witnessed the case and it left a deep impression. It is thought that his observations on miserliness and the machinations and bureaucracy of the legal system later surfaced in works such as Nicholas Nickleby (1838-39), A Christmas Carol (1843), Dombey and Son (1848) and Bleak House (1853).

Sold at Dreweatts, Newbury, April 2019, £1300 + 25% buyer’s premium

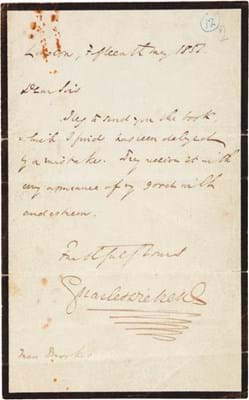

To Brookes of Sheffield

Last seen at Christie’s in 2012, when it sold for £50,000, this inscribed presentation first of Dickens’ own favourite among his books, David Copperfield (1850) took more than double that amount when reoffered as part of the Drizen library last year.

In a contemporary dark green morocco binding, it was inscribed in May 1851 on the half-title to Brookes of Sheffield, a character referred to several times in the book.

The gift, a copy from Dickens’ own library, had followed a correspondence with John Brookes of Sheffield, a manufacturer of knives and razors who had sent Dickens a case of cutlery. It was accompanied by a short note reading “I beg to send you the book which I find has been delayed by a mistake.”

Only two other inscribed presentation copies of David Copperfield have been sold at auction since 1975.

Sold at Sotheby’s, London, September 2019, £110,000 + 25% buyer’s premium

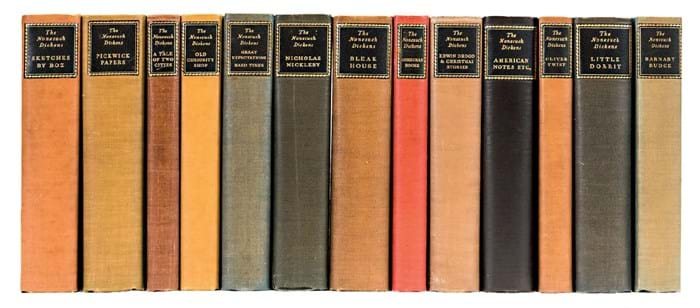

The Nonesuch edition

Since publication, Dickens books have been reissued in numerous editions. Most are of only modest secondary market value – with the odd exception. Perhaps the most popular posthumous printing is the 1937-38 Nonesuch Press edition.

A total of 877 of these 24-volume sets were made – the peculiar limitation due to the inclusion with each of one of the original steel or woodblock picture plates used by Chapman and Hall in the first printings of each title.

This particular copy includes the Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz) woodblock ‘Kit enters the office’ from The Old Curiosity Shop. Phiz was Dickens’ preferred illustrator who contributed to 10 of his novels.

Sold at Forum Auctions, London, March 2020, £2800 + 25% buyer’s premium

A great copy of Great Expectations

The Lawrence Drizen collection offered at Sotheby’s in London was topped by this superbly preserved 1861 first issue copy of Great Expectations.

Few really fine copies of the novel survive as Mudie’s Circulating Library, whose subscribers often borrowed only one volume at a time, bought up almost all of Chapman & Hall’s 1000 first issue copies of the book. Many were borrowed multiple times and quickly deteriorated.

The previous high for a copy was recorded at Sotheby’s New York in 2015, when the copy from the Self collection –$80,000 at Christie’s New York in 2008 – returned to auction to sell at $110,000 (£69,300). Condition is everything here. A more typical first-issue copy of Great Expectations in a later binding might bring a low four-figure sum.

Sold at Sotheby’s, London, September 2019, £140,000 + 25% buyer’s premium

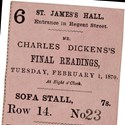

The farewell performance...

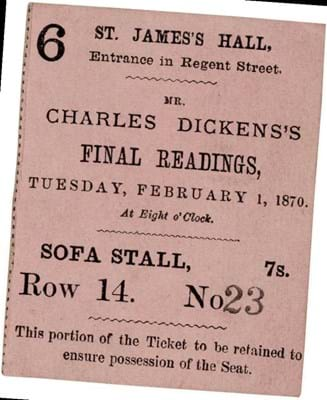

Dickens was renowned for powerful theatrical public readings of his own novels and vocal impersonations of his many characters. He gave close to 500 performances in his lifetime in the UK and the US.

The ‘Final Readings’, delivered in a fragile state of health, included episodes from Pickwick Papers, Oliver Twist and the perennial Victorian favourite A Christmas Carol.

After the last performance to an audience of more than 2000, Dickens made an emotional speech which ended: ‘’... from these garish lights I vanish now for evermore... ‘’, words which were inscribed on his funeral card distributed at Westminster Abbey three months later.

This ticket stub for a place in the sofa stall (the best seats in the house) on February 1, 1870, was priced at 7s. Sold at Dominic Winter, South Cerney, December 2019, £660 + 24% buyer’s premium

...and the final curtain

This silver-mounted tortoiseshell cigar case and vesta case are inscribed To Charles Dickens from J L Toole 1869.

The actor and theatre manager John Lawrence Toole (1830-1906) ranked among Dickens’ favourite stage performers with this gift probably connected to Toole’s performance in Henry James Byron’s Uncle Dick’s Darling at the Gaiety Theatre in December 1869.

Dickens was an avid theatre-goer who claimed to have once watched a play every day for three consecutive years. This was the final play he saw before his death.

Sold at Sotheby’s, London, July 2018, £7000 + 25% buyer’s premium

The Dickens industry

This early-20th century oak chair is carved to the back as Mr Micawber and to the seat with a portrait of Dickens and the inscription Mr Micawber Waiting for something to Turn Up.

Both the author and his huge cast of loved and unlovely characters spawned an industry of mass-produced souvenirs – an irony for a man who stipulated in his will that no memorial should be erected in his honour.

Sold at Chorley’s, Prinknash Abbey, March 2020, £220 + 22.5% buyer’s premium

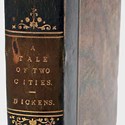

The worst of spelling

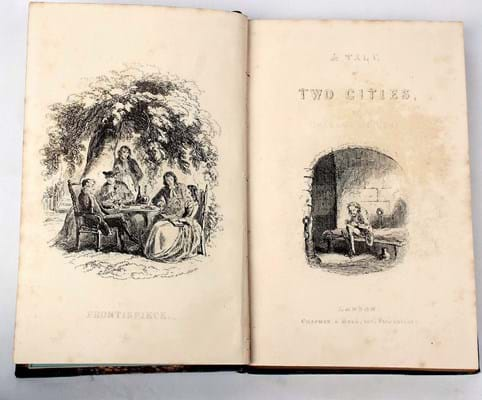

As well as the information found on the imprint, most Dickens first editions come with typographical or pictorial tell-tales.

This 1859 first issue copy of includes two well-known errors: ‘affetcionately’ on page 134 and page 213 is numbered 113. The engraved plates are by Phiz – his last work for Dickens.

Copies in original publisher’s cloth will bring much more – the example in the 2008 Self collection made $7500 (£6000).

Sold at Bristol Auction Rooms, January 2020, £1300 + 20% buyer’s premium