When the late Dennis Silk bought a pottery figure of Queen Victoria at a Dorset antiques shop in 1968, a small obsession began.

An English first-class cricketer and friend of war poet Siegfreid Sassoon in his youth and warden of Radley College in Oxfordshire from the 1960s, he (like a substantial number of fellow post-war professionals) devoted much of his leisure time to the pursuit and study of Staffordshire portrait figures.

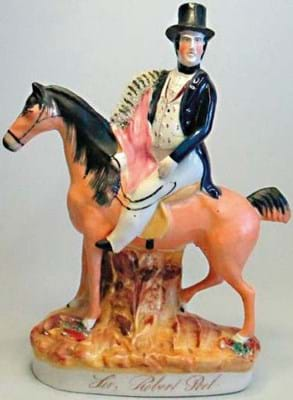

Offering a vast cast of popular and contemporary characters in ceramic form, portrait figures were a phenomenon of the Victorian era.

Advances in press moulding and slip casting meant pottery figures could be made relatively cheaply, while decent likenesses became possible from the 1840s when good-quality illustrations were made available in the form of sheet music, playbills, penny prints and the Illustrated London News.

It lasted for just over half a century: figures of Edward VII and his queen Alexandra of Denmark are among the last of the Staffordshire’ flatbacks’.

Although today Victoriana in general and flatback figures specifically are often tarred with the brush of ‘old-fashioned taste’, this is a collecting area that rewards anyone with a love of history.

The great, the good and the bad

From heroes to villains, the Silk collection, for sale at Hansons (25% buyer’s premium) at Bishton Hall, Staffordshire, on November 15, numbered 261 different figures that crossed the full spectrum of subjects.

It was among the first designated sales in this field since the heady days of the 1980s and early 1990s. Catering to popular demand, the royal family was by far the most common subject for cheap and cheerful portrait figures but topicality was everything.

Military and naval subjects, statesmen and politicians, stars of theatre, circus or sport were also strong sellers. Staffordshire during the 19th century was a centre of non-conformist religious activity, something reflected in the range of portraits produced of Methodists and Baptists.

More curious was the draw of figures of criminals: notorious murderers of the period were captured in clay for posterity and commercial gain. Several of the most desirable figures in the Silk collection were the bad guys.

Take your pick from William Palmer, the Rugeley Poisoner (£1900 from a US collector), James Rush of Stansfield Hall murder fame (£540) and Marie Manning, convicted of the ‘Bermondsey Horror’ (£320).

Alan Sturrock, president of the Staffordshire Figure Association, was quick to praise the collection’s contents: “It was a very comprehensive collection put together over some 40 or 50 years with the care and eye of a man who certainly loved and knew his subject.”

He and other collectors were pleased to see the collection offered as single figures rather than as group lots designed to meet price thresholds.

“The buying public want Staffordshire figures sold individually or in their pairs. The vendor’s family would have done a great deal worse had the figures been lotted in groups to enable the auctioneer to finish the sale more quickly.”

Most pieces were properly catalogued with reference to the classic text on the subject: Staffordshire Portrait Figures and Allied subjects of the Victorian Era by Surgeon Rear Admiral PD Gordon Pugh (1970) whose own collection was acquired by the Potteries Museum & Art Gallery in 1980.

But however good the collection, it is difficult to buck overall market trends. This is, as they say, ‘a great time to buy’.

The more common figures, or those that depict generic types rather than specific subjects, have seldom been better value, typically selling for between £10-50.

Condition was also a factor. A number of the figures carried restoration that was quite acceptable at the competitive moment Silk was buying but less permissible today when the collecting base is smaller.

Nonetheless, there were some 53 different purchasers for the sale representing all of the major collecting nations (US, Canada, Malta, Ireland and Australia) plus a buyer from Germany.

A healthy number of figures were sold for £100-300 each and the rarities that appealed to established collectors made decent sums. There was nothing here to challenge the auction record books (in 2003 Christie’s New York sold a figure of the Victorian lion tamer Isaac Van Amburgh for $7000) but a sale total of £21,500 and a near sell-out is proof that Staffordshire can still merit the specialist sale treatment.