The flagship departments at leading London auction houses – Contemporary art, Impressionist & Modern and Old Masters – have all faced a similar fate during the coronavirus pandemic. All have been affected by reduced supply that has hit turnover.

The overall number of lots has been reduced, while fewer stellar items have been forthcoming.

Old Masters has certainly had such difficulties since March 2020 but the reality is that supply issues are nothing new in this market.

The pandemic seems to have intensified existing market conditions and made the old truism more keenly felt: sourcing fresh material remains the key to unlocking this selective sector.

The latest series of Old Master auctions in London demonstrated the turnover issue quite starkly. The overall premium-inclusive total was £39.2m, down on the £49.1m at the equivalent series in 2019, which itself was a somewhat weak year generating around half of the 2018 total.

In a ‘normal’ year, the evening sales would run to around 50 to 60 lots at each saleroom, but they were slimmer this season with Christie’s offering 44 and Sotheby’s just 27.

True, some vendors may have chosen to sell privately rather than at auction. Other lots may have been held back for the anticipated stronger auctions in New York in 2021. And a few late withdrawals also affected these sales (such as a Bernadino Luini estimated at £3m-5m at Christie’s).

But, undoubtedly, it was the difficulties in sourcing works that had the most significant effect on supply here. Despite all that, however, it would be wrong to say that the sales performed badly in terms of actual prices fetched by individual lots.

‘An appetite remains to buy great art’

Christie’s (25/20/14.5% buyer’s premium) December 15 evening sale in particular posted some solid results for what was on offer and achieved a decent scattering of artist’s records – six in total.

While 38 of the 44 lots sold (86%) for a premium-inclusive total of £22.8m, the sold-by-value rate was an impressive 97% – higher than any Old Master sale that the department heads could recall.

Christie’s head of Old Master pictures Henry Pettifer acknowledged that specialists such as himself were “operating in a difficult, challenging environment where business-getting has become tougher”.

However, he felt that the freshness of the material that had come through for the evening sale was “incredibly encouraging” and a “statement of confidence in the market” from the vendors who were prepared to consign.

“An appetite remains to own great art and buy the best that the market has to offer. Without the art fairs and other outlets, there’s a scarcity of great material and so the fact that all our top lots were fresh to market was what really excited the buyers.”

Live link stateside

The auction held at King Street was Christie’s first Old Master sale which operated with a live link to the company’s New York saleroom (specialists in the Big Apple were relaying real-time bids). Having experimented with this new format in previous mix-category auctions, the process seems to have become slicker and around 20% of the sold lots ended up going to the US.

Pettifer said that in the Covid-19 era of auctions there was “not so much emphasis on physical inspection”. This has been a notable change to the market in many sectors, even though Old Masters are thought to be one of the areas where buyers are most keen to view lots and assess their condition.

Certainly prospective bidders on one of the evening’s star lots had their restorers examine it carefully prior to the sale.

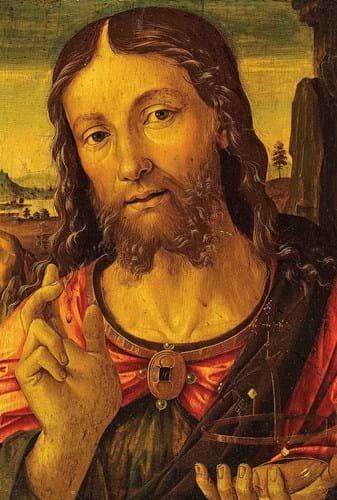

The rare and striking Salvator Mundi by Florentine master Domenico Ghirlandaio (c.1448-94) was among the key market-fresh works at the sale. But it was in a dirty state with a layer of varnish throughout – it may have previously been owned by a heavy smoker.

Unseen in public for several generations, it had been acquired by the grandparents of the vendor in the 1950s from Paris dealer Galerie D’Atri. Following its recent ‘rediscovery’, its attribution to the early Renaissance painter, whose work has hardly ever appeared at auction, was confirmed by Christopher Daly of Johns Hopkins University. He suggested a date of c.1485.

The restorers who looked at the 13¼ x 9½in (33 x 24cm) tempera and oil on panel seemingly gave it the thumbs-up and believed that it would clean superbly. The current picture had some minor later additions (confined to the edges) but infrared imaging revealed outlines of underdrawing, showing Ghirlandaio’s compositional alterations and intriguing thought processes.

This made it a tantalising commercial prospect – even if not quite at the level of a certain other Salvator Mundi sold by Christie’s in the last few years.

Perhaps the whole subject of Salvator Mundi has become more desirable to collectors since the record $400m Leonardo in 2017? Either way, the Ghirlandaio, which predated the Leonardo by over a decade, showed that the representation of Christ as the ‘Saviour of the World’ – holding a glass orb in his left hand and raising his right in benediction – was a popular subject in Italian art well before Leonardo.

At the sale, at least five parties pushed the bidding beyond its £300,000-500,000 estimate before it was knocked down at £1.8m. The buyer was bidding through François de Poortere of Christie’s New York who, incidentally, had been the saleroom’s representative for the underbidder on the Leonardo.

“You finally got your Salvator Mundi, François,” said auctioneer and Christie’s global president Jussi Pylkkänen as he knocked down his gavel.

Fresh banquet

The top lot of the sale overall, a fine banquet still-life by Jan Davidsz de Heem (1606-84) was also a work in need of a clean. Here too though, bidders were more attracted to its freshness and rarity. It had been in the same private English collection since the 19th century and was one of four striking works with that subject completed during the artist’s desirable early Antwerp period.

Estimated at £4m-6m, the picture drew competition from phone bidders but was sold for a record £4.8m to art agent Wentworth Beaumont who was in the room in London.

Pettifer said the price represented the highest price (in sterling) achieved for any still-life painting in the Old Master category.

Drum up support

A strong competition also came for another freshly sourced and well-preserved work: a rare painting by the Dutch artist Frans van Mieris The Elder (1631-85).

The Drummer Boy, a small oil on copper that was signed and dated 1670, was believed to have been acquired by the Elector of Bavaria in the early 18th century for his gallery in Schloss Schleißheim. It had entered the Alte Pinakothek in Munich but was de-accessioned in 1929 and had been untraced since then. It came to auction from a private British collection.

Measuring just 6¾ x 5½in (17 x 14cm), it was admired for originality, handling and charming subject.

Four bidders pursued it against a £800,000-1.2m estimate and it sold at £1.45m to a private European buyer on the phone. It was the second-highest auction price for the leading Leiden painter – only behind the £3.2m for Young woman in a red jacket feeding a Parrot that sold at Sotheby’s in December 2008.

Packing a punch

Among the British pictures in the sale, a portrait by William Hogarth (1697-1764) turned a few heads and sold on top estimate. Again, crucially, it was fresh – it had been acquired by Henry Lowther, 3rd Earl of Lonsdale (1818-76) and was consigned by the trustees of the Lowther estate.

The Pugilist was believed to almost certainly depict James Figg (1684- 1734), a professional prize fighter who is recognised as the first English bare-knuckle boxing champion. This small scale painting, a 17 x 12in (43 x 31) oil on canvas, depicts him as a quarterstaff player – a form of stick-fighting that had been practised since medieval times.

The catalogue stated that it was “probably painted as a gift for one of Hogarth’s close circle, most of whom were admirers of the sport” and the spontaneity and character of the portrait suggested it was painted from life.

Estimated at £200,000-300,000, it sold at the upper end of expectations to a UK private buyer.

Putting in a decent performance, it showed that while supply might be down, Old Masters can still pack a punch.