Charting unknown waters is the specialist subject of dealers in antique maps, but the post-pandemic world is testing everyone’s sense of direction.

International travel is opening up. Shops and live events are back and the London Map Fair at the Royal Geographical Society (June 11-12) is approaching at a rate of knots. But who will come, and what will they want?

Among dealers, there seems to be a real appetite to be out and about again. The map fair is solidly booked. There will be fewer EU dealers than usual – potential exhibitors have not yet cracked the conundrum of how to get maps back into their home countries with a minimum of fuss – but a very strong showing from North America.

There are good reasons to believe the confidence is justified.

Lockdown did not dampen enthusiasm for antique maps: auction houses and online dealers reported bumper sales. Pessimists suggested it was a blip born of boredom, but those months of furlough might just have inspired a new generation of collectors. As well as long walks and gardening, extended time at home appears to have reintroduced people to the pleasures of owning beautiful and interesting things.

Open minds

Significantly, these new customers are coming to the world of old maps with open minds, free from prejudices or preconceptions.

A few decades ago, an older generation of map sellers could be decidedly sniffy about anything printed after 1900 (in some cases, 1800). Modern maps were largely under-researched, under-represented in public and private collections and consequently under-valued. This always seemed curious, especially given the rare book trade’s early acceptance of modern first editions. Thankfully, this imbalance has largely been corrected.

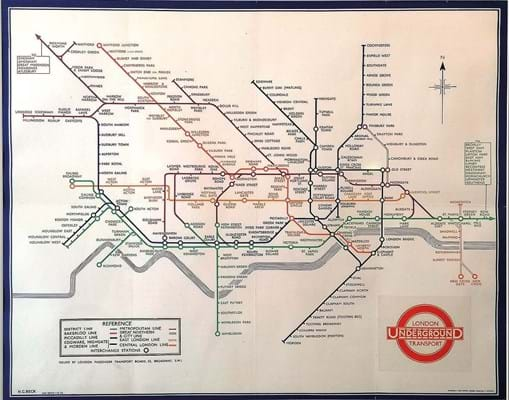

For example, one of the first-time exhibitors at the map fair will be offering a 1933 London Underground platform map (Iconic Antiques, £55,000). This was only the second time that Harry Beck’s famous diagram was printed in poster form for display in stations, the first in this double-crown size, the first to use circles for interchange stations and the first to use the new London Transport roundel, and the only poster to show a compass rose.

Beck’s diagram is now firmly established as one of the most original examples of 20th century cartography, and other maps of the era have now achieved equally solid status.

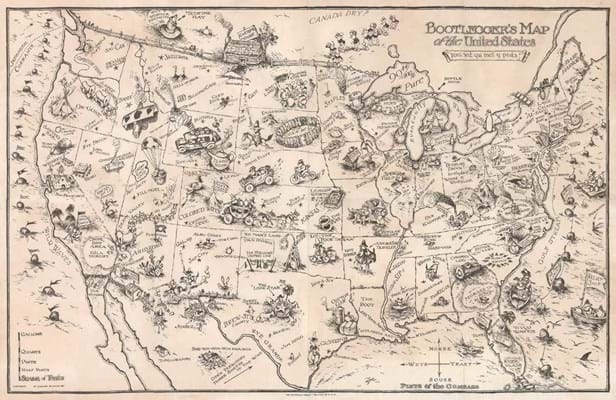

Edward McCandlish’s Bootlegger’s Map of the United States, published in Detroit c.1926 and satirising prohibition (New World Cartographic, $1600), is described as ‘one of the “must have” pictorial maps of the 20th century’. The compass rose on this map denotes Pints of the Compass reading Norse, Souse, Yeast and Wets.

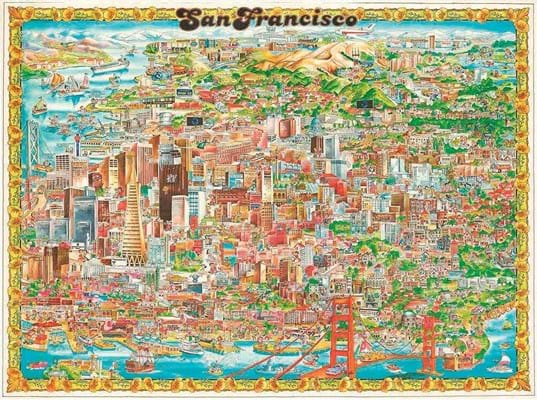

Interest now extends deep into the second half of the century. Barbara Spurll’s pictorial map of San Francisco was issued as recently as 1978 (Geographicus, $500) but it is already possible for the cataloguer to note that only the 1982 edition has been located in institutional holdings, and that it is ‘extremely scarce to market’.

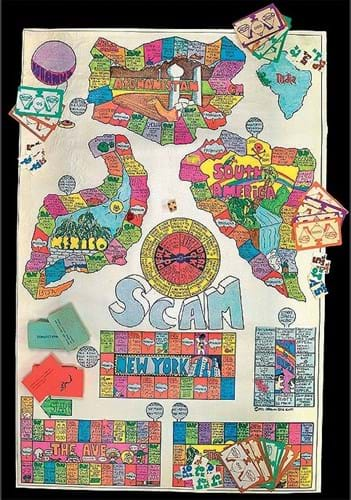

Collecting cartographic games is no longer confined to early, educational examples and, indeed, now includes games that a 19th century educationalist would scarcely have approved of. Scam: The Game of International Dope Smuggling (Daniel Crouch Rare Books, £5000) appeared in 1971, published (where else?) in Berkeley, California, in the year Nixon declared his ‘War on Drugs’.

Scam: The Game of International Dope Smuggling, 1971 – £5000 from Daniel Crouch Rare Books, London at the London Map Fair.

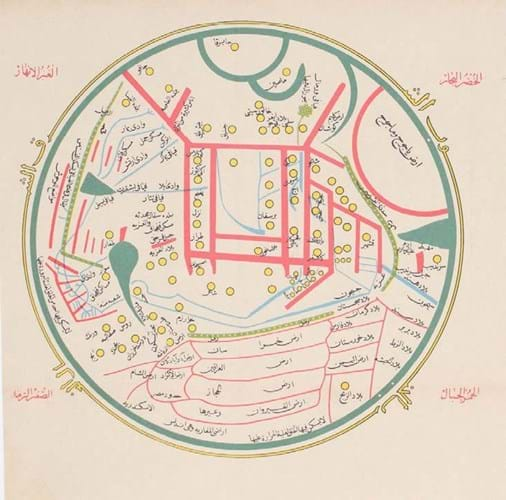

The appeal of maps produced outside Europe and North America has also burgeoned. Mahmud Kashgari’s world map in Arabic was drawn in the 11th century to illustrate his ‘Diwan Lughat al-Turk’ (‘The Compendium of the Turkic Dialects’).

It was lost for centuries before its rediscovery in Istanbul’s secondhand book market by the bibliophile Ali Amiri, who then supervised its publication in 1917.

Mahmud Kashgari, world map in Arabic, Constantinople, 1917 – £2500 from Bryars and Bryars, London at the London Map Fair.

This is quite distinct from mapping made in the western tradition or for westerners. Oriented with East at the top, in terms of scale and detail the map is focused on the Turkic heartlands of central Asia, but its reach is far greater: Kashgari shows the Great Wall of China, and it is also the earliest known map to include Japan (Bryars and Bryars, £2500).

Folding maps, dissected and laid on linen, were once such a niche interest that they were sometimes removed from the backing and re-joined to increase their wall-power.

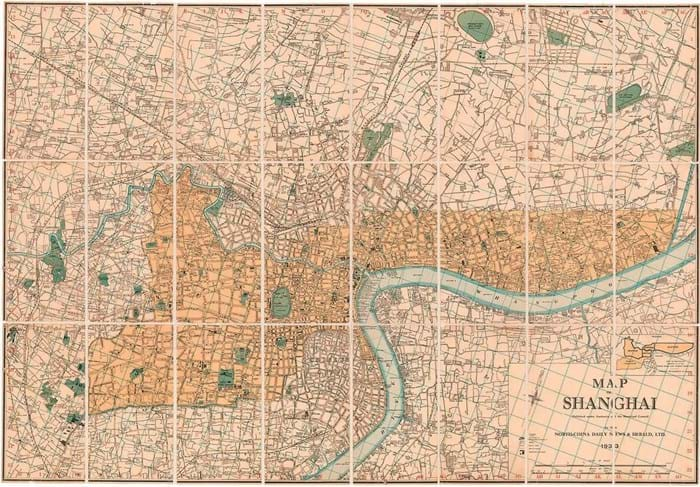

Fortunately, that fate has not befallen a copy of such a rare 1933 map of Shanghai (Vetus Carta, $9000) published by the China Daily News and Herald, which is focused on the International Settlement.

China Daily News and Herald, Shanghai, 1933 – $9000 from Vetus Carta, Ottawa at the London Map Fair.

Shanghai’s notoriously humid climate is one factor behind its great scarcity (only one institutional example has been located) and clearly this example needed conservation, but the modern solution is to re-line it with fresh linen, preserving its integrity as a folding map.

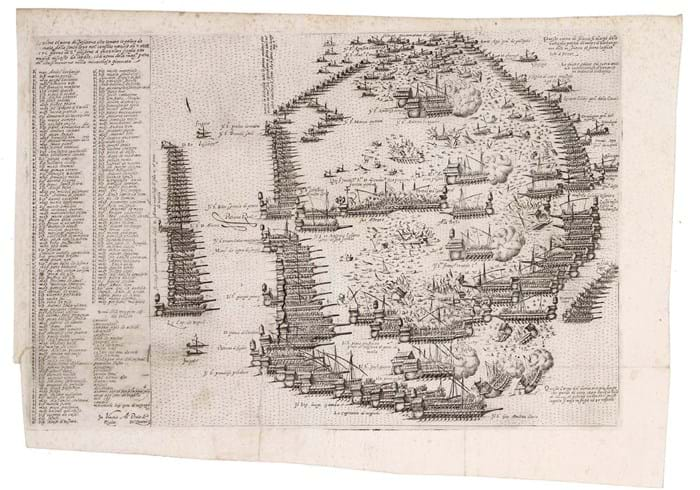

Of course, the appeal of cartographic rarities has never really died away. Take Domenico Zenoi’s plan of the battle of Lepanto, the decisive naval engagement off the coast of Greece in 1571 which largely checked the Ottoman advance in the Mediterranean. It was the largest sea battle since classical antiquity and the last in Europe where both sides relied on galleys and galleases, the descendants of ancient triremes.

Venetian and Spanish vessels were the backbone of the forces fielded by the Catholic Holy League, and their captains are listed in two columns to the left of the image, followed by a shorter list of Ottoman commanders.

Zenoi’s map was published in Venice at the time of the battle. Today it is too scarce to be subject to changing fashions (Bryars and Bryars, £15,000).

Domenico Zenoi, plan of the battle of Lepanto, Venice, c. 1571 – £15,000 from Bryars and Bryars, London at the London Map Fair.

However, sometimes it is worth taking a second look at the familiar – or perhaps that should be the overfamiliar.

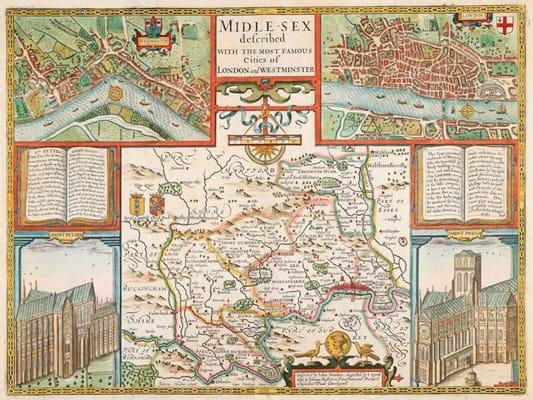

Anyone seeking to create the perfect Mid-century modern interior should really be hunting for 17th century county maps to hang on the walls above their Eames furniture. Look at the backdrop to a Connery Bond film and that is exactly how the MI6 offices were accessorised.

It was the ubiquity of decorative early maps, once hanging in pubs, offices and dining rooms across the nation, that led to their temporary commercial eclipse. They blended too easily into the background.

However, for anyone coming fresh to the antiques market, with no hang-ups about collecting something different from their parents, such things now seem undervalued. And far from dull.

Ogilby revised

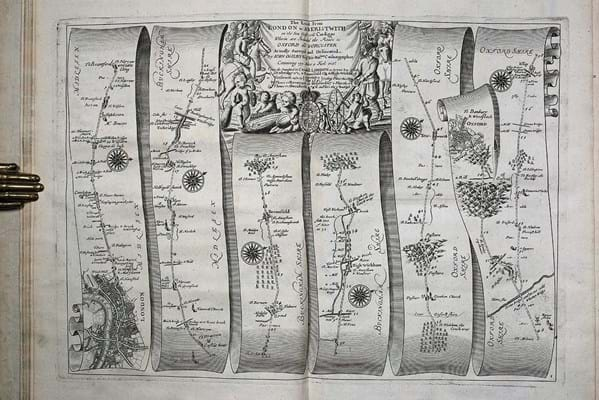

The last London Map Fair lecture was delivered by Alan Ereira, biographer of John Ogilby, the creator of the first British road atlas which was published in 1675. His atlas aimed to inform and reassure passengers in the stagecoaches which were proliferating in Restoration Britain. Thousands of miles of roads were surveyed for the project, smaller towns appeared in detail for the first time, and it was largely thanks to Ogilby’s influence that the statute mile was set at 1760 yards.

That much is well known. Far more illuminating is the knowledge that Ogilby devised the project late in life after earlier careers as a dancing master, soldier, spy, theatre impresario and translator.

‘By investigating these incarnations, through which Ogilby survived the turbulent 17th century, Ereira presented a provocative new reading of Ogilby’s innovative and beautiful atlas as a work of royalist propaganda - even expressed through the routes which he chose to include or emphasise.’

It is difficult to look at them in quite the same way again.

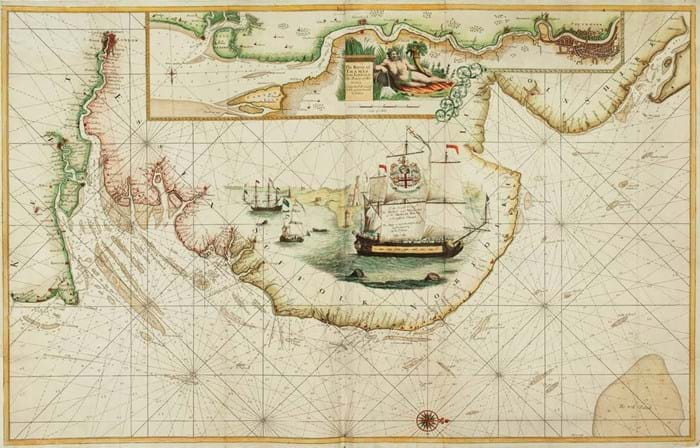

This year the guest speaker at the RGS is Paul Hughes, a master mariner who has written a new biography of Captain Greenvill Collins, creator of the first British atlas of British coastal waters. First published in 1693, it was the standard work for a century.

Captain Greenvill Collins, chart of the Thames Estuary, London c. 1693 – £1000 from Altea Gallery, London at the London Map Fair.

Again, his sea charts have been popular with generations of collectors. However, fewer people appreciate that the atlas evolved from national embarrassment that the best charts of the British coast were Dutch, especially in the aftermath of the humiliating Dutch Medway raid of 1667, or that Collins had to plead for finance and support from three successive monarchs. Hughes will give new layers of meaning to these ‘old friends’.

It just goes to show that there is plenty to be discovered by anyone looking at old maps with fresh eyes.