Claude Aguttes, auctioneer, on the rostrum for the first of the Aristophil sales in December 2017.

Image copyright: Aguttes/Drouot

For more than a decade, the Parisian firm Aristophil, run by dealer Gérard Lhéritier since 1991, was the biggest buyer in a booming documents market.

Acquiring spectacular works at auction and through dealers, the company encouraged investors to speculate on historical letters and manuscripts of all types with the promise of an annual return of 8% or more.

Close to 21,000 clients were sold the dream of owning a piece of Einstein, Mozart, de Gaulle, van Gogh or Proust.

In France, the proceeds were even tax free since art and antiques were exempt from the ISF wealth tax. What could possibly go wrong?

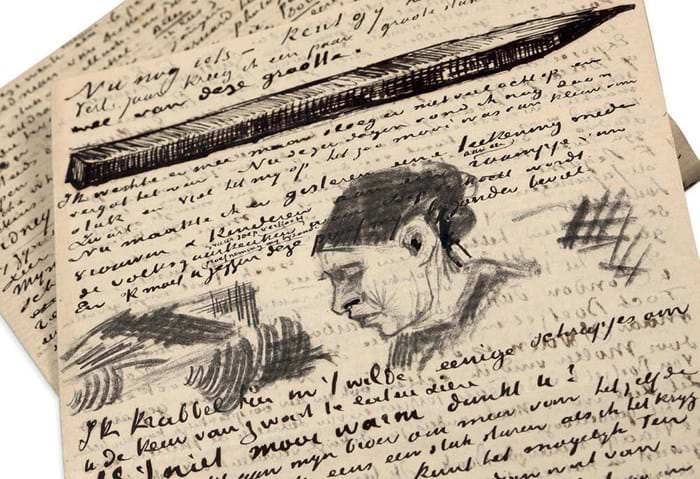

For five years, from 1881-85, Vincent van Gogh and the young Brussels-based painter Anthon van Rappard exchanged what they called a “friction of thought”. A long eight-folio letter penned to van Rappard, dated The Hague, March 5, 1883, included five pencil or ink sketches. In it van Gogh discusses the merits of a variety of different artist materials, his preferences in Dutch art and his love of Charles Dickens. “In my view there’s no other writer who’s as much a painter and draughtsman as Dickens”, he says. Estimated at €250,000-300,000, it realised €460,000 (£404,800) on June 2018 at Aguttes. A premium of 30%/27.6% was charged on all lots.

Image copyright: Aguttes/Drouot

Warning signs

It was not just old heads in the book trade that openly questioned the viability of the project.

By December 2012 the nostrils of the financial regulator had caught a malodour.

The Autorité des Marchés Financiers was warning the public against “atypical investments offered to investors in sectors as diverse as letters and manuscripts, works of art, stamps, wine, diamonds and other niche sectors.”

But by then the horse had well and truly bolted.

Tens of thousands of historical documents had been acquired, 54 individual themed collections formed, and contracts totalling €700m signed, before the Aristophil bubble began losing air in 2013.

Charges made

Shortly after the company was placed into compulsory liquidation in January 2015, Lhéritier and five others (including the Parisian bookseller Jean-Claude Vrain) were indicted on charges of organised fraud and tax evasion and the collection seized.

The complex legal investigation into a ‘pyramid’ selling scheme at Aristophil continues.

However, the mammoth disposal of the collections at the Drouot in Paris, has recently concluded.

In quantity and quality, we may never see the like again.

“The mission has been successful. Today, I am relieved and truly proud”, says auctioneer Claude Aguttes, whose Neuilly-sur-Seine firm was asked by the High Court to begin the resale process back in October 2016. It involved the logistical challenge of moving, storing, conserving and cataloguing all of the inventory and a workable strategy for selling piecemeal the entire collection – the great, the good and the ordinary – within a set time frame.

A dedicated team of up to a dozen people was hired for the duration of the project and three other Parisian auction houses (Artcurial, Drouot Estimations and Ader-Nordmann) were approved by the court to aid with the dispersals under the name OVA (Les Opérateurs de Vente pour les Collections Aristophil.

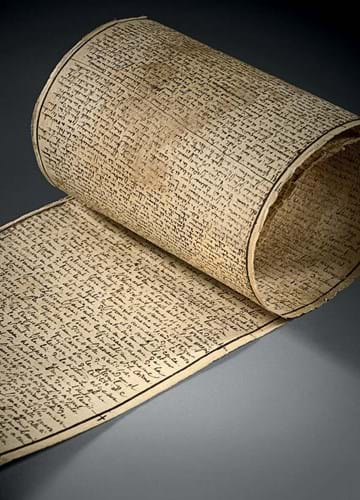

The 56 sales that took place over five years (December 2017 to November 2022) have generated some remarkable numbers while deciding the fate of hugely important documents – such as original 39ft-long manuscript of the Marquis de Sade’s 120 Days of Sodom and Andre Breton’s handwritten Manifeste du Surrealisme.

Some 286 cubic metres of controlled storage space was required (storage costs alone were €1.8m).

Close to 136,000 individual items were catalogued into 6900 lots across 56 sale catalogues. Total costs were €4m and the total receipts around €108m.

That includes the government and private money that bought the three items deemed ‘national treasures’ plus the 335 lots that were pre-empted by more than 20 public institutions.

Total of 56 sales

Saturating the market was an obvious cause for concern for both Aguttes and the many stakeholders in this collecting field.

The decision was taken to create a total of 56 thematic sales covering subjects as diverse as fine art, 19th and 20th century literature, music, history, science and postal history.

There were two sessions of four auctions annually over five years.

There was no expectation that all of the money invested in Aristophil contracts would be recouped. The sums of money were just too great.

Emblematic of the scheme’s excesses was the Einstein Besso correspondence on relativity that, bought for €559,500 in 2002, had been sold to Aristophil the following year for €3.5m and then resold in myriad shares to investors for €12m.

Later offered at €24m, when sold at Christie’s in Paris (in association with Aguttes) it hammered at €9.5m.

However, despite the challenges posed by the return of so much merchandise, Claude Aguttes had been confident the market would be strong enough to cope.

“It was necessary to differentiate the impact of financial [scandal] from the health of the art market. The rare book trade was not destabilised.

“In fact, the high quality and rarity of the Aristophil manuscripts have helped boost the market.”

Emotional rescue

Roughly half of the buyers were French with a further 28% of lots sold to other Europeans and 22% from the rest of the world. Buyers from the UK, US, China and Russia were particularly active.

So, knowing the size and complexity of the task, would Aguttes choose to do it all again?

“Was it my recklessness, my passion for rare objects, or the challenge that pushed me to attempt the unthinkable?

“Never before did an auctioneer have the opportunity or the courage to conduct a sale like this.

“One day I will have to write the full story of this saga. The last sale was very emotional. To think that it was over seemed almost impossible. What a collection!”

Aristophil: timeline

1990s: Paris dealer Gérard Lhéritier creates Aristophil, encouraging investors to speculate on the rising value of historical letters and manuscripts. Each investor consents to the works being stored by Aristophil for an agreed period of five years or more with the promise of 40% returns. Subsidiaries are opened in Austria, Belgium, Switzerland and Hong Kong.

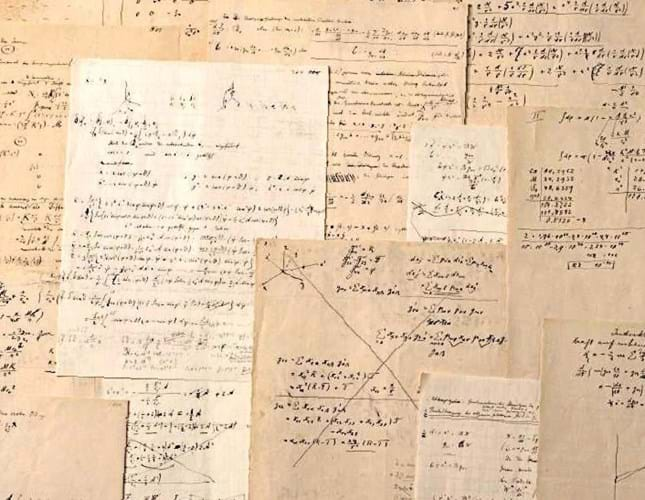

2002: Aristophil purchases the 54-page correspondence between Albert Einstein and the Swiss mathematician Michele Besso for $559,500 at Christie’s New York. It is valued at €12m to Aristophil’s investors, and later offered for resale at €24m.

The correspondence between Albert Einstein and Michele Besso, sold for $559,500 at Christie’s New York.

Image copyright: Christie’s Images

2003: The Autorité des Marchés Financiers (AMF) publishes the first of several warnings about the Aristophil business model. After an investigation, a court finds that investment in historical manuscripts does not come within the scope of the financial regulator.

2012: Lhéritier creates the Musée des Lettres et Manuscrits in Paris where trophy acquisitions are exhibited.

2012: In a bizarre twist, Lhéritier wins the largest ever EuroMillions jackpot awarded in France at €170m. He immediately invests €40m of the prize money into his company which was, said his lawyer Francis Triboulet, “proof that Aristophil was legitimate”.

December 2012: The AMF warns the public again about “atypical investments offered to investors in sectors as diverse as letters and manuscripts, works of art, stamps, wine, diamonds and other niche sectors”.

2013: Aristophil is no longer able to meet the repayments promised to its customers.

March 2014: Suspecting a pyramid or ‘Ponzi’ scheme, the French judiciary launch an investigation.

November 2014: The Musée des Lettres et Manuscrits, the Aristophil headquarters and those of subsidiary companies are searched by 100 officers from the anti-fraud squad. The accounts of the company are frozen and the whole of the collection placed under seal.

January 2015: Aristophil, heading for bankruptcy, is placed into compulsory liquidation.

March 2015: Lhéritier is indicted on charges of organised fraud and tax evasion. The company assets are frozen by the Ministry of Justice to allow investors time to file claims. Legal firms begin registering complaints and a series of class action groups are established.

March 2015: L’association nationale de defense des investisseurs contre Aristophil (Adilema), formed in March 2015 to represent the interests of 600 Aristophil victims, initiates civil proceedings against the bankers used by the bankrupt company.

2016: The authorities say any sale will not recover the full amount invested. Two experts assigned by the judiciary to value the documents, Christian Galantaris and Jerome Cortade, say manuscripts were sometimes sold by Aristophil to investors for many times their true market value.

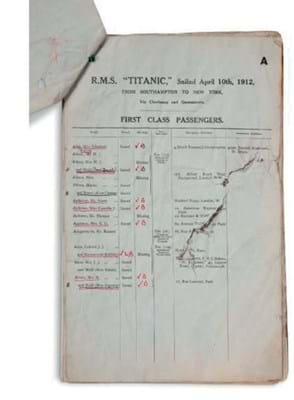

September 2016: Following a break in the legal impasse, elements of the Aristophil collection are returned to investors. It is revealed the company had 26,297 contracts for items owned by multiple owners (so-called Cotalys contracts) and 4458 agreements (Amadeus contracts) where documents were fully owned by an individual.

March 2017: Neuilly-sur-Seine auction house Aguttes is appointed by the High Court to begin the process of cataloguing and conserving the collection. While other auction houses had offered to sell the choice lots, the court chose a firm prepared to take on the entire stock.

March 2017: Aguttes is asked to begin the resale process. Three other auction houses, Artcurial, Drouot Estimations and Ader-Nordmann, are approved by the legal administrators and the association OVA (Les Opérateurs de Vente pour les Collections Aristophil) is formed.

December 2017: The first sale of 190 choice lots is curtailed when manuscripts including the original text of the Marquis de Sade’s 120 Days of Sodom (estimate €4m-6m) and Andre Breton’s handwritten Manifeste du Surrealisme (€4.5m-5.5m) are withdrawn from sale. Aguttes said the French government has 30 months to make an offer at the “international market value price”. The auction totals €3.8m. Ursule Mirouët, one of only two manuscripts by Honoré de Balzac still in private hands, sells for over €1m.

June 2018: The bulk selling of the collection begins with a €17.6m series of seven auctions offered over four days at Drouot.

July 2021: France’s Ministry of Culture announces the €4.55m acquisition of the 120 days of Sodom manuscript for the Bibilotheque Nationale de France.Autograph manuscripts by Andre Breton, including the two manifestos of Surrealism, are also acquired.

November 2021: In association with Aguttes, the Einstein Besso manuscript sells for €9.5m (£8.4m), an auction record for any science manuscript, as part of The Exceptional Sale at Christie’s in Paris.

November 2022: Aguttes conducts the 56th and last major auction from the Aristophil collections.

National treasures

Declared a national treasure and withdrawn from sale in December 2017, the 39ft (11.9m) long manuscript of 120 Days of Sodom manuscript was acquired for €4.55m by the Bibilotheque Nationale de France in July 2021 with help from Emmanuel Boussard, an investor and former investment banker.

Sade wrote the controversial story in 37 days in 1785 while imprisoned in the Bastille. He had hidden the manuscript, penned in a tiny handwriting on sheets of paper, in a stone wall when he was transferred days before the storming of the Bastille on July 14, 1789.

Later recovered and mounted as a single roll, it was sold, resold and then published for the first time by a German doctor in 1904. In 1929 Viscount Charles de Noailles bought the manuscript for his wife Marie-Laure who was a direct descendant of Sade’s.

It became part of the Aristophil investment scheme around 2007 for an estimated €7m.

Just three lots in the Aristophil collections were deemed national treasures.

The other two items acquired privately by the the Bibilotheque Nationale were the manuscripts for Poisson Soluble by André Breton (acquired at €2.7m) and a set of eight parchment portolan nautical charts made in 1648 by Honoré Boyer, the only record of a talented cartographer from Marseille (€266,500).

Pre-emption

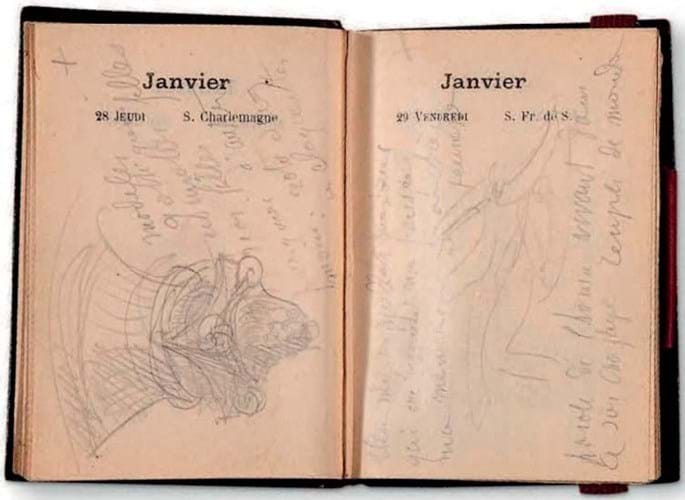

French institutions exercised their right of pre-emption on 335 occasions across the Aristophil sales series. The Musée Rodin pre-empted two of Auguste Rodin’s notebooks, both formerly part of the library of the perfumer and bibliophile Lucien-Graux (1878-1944), as Aguttes sold letters and manuscripts of leading 19th and 20th century artists on June 18, 2018.

One c.1905 example (shown above) had been used during trips in the Paris region, Beaugency and Touraine, and another on visits to Blois and Touraine in 1904. Filled with notes on art and architecture, the pages included many rudimentary drawings, including sketches for Rodin’s monument to the French dramatist Henry Becque. They sold at €15,000 (£12,200) and €16,000 (£14,050).

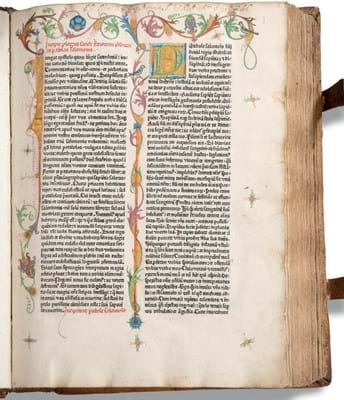

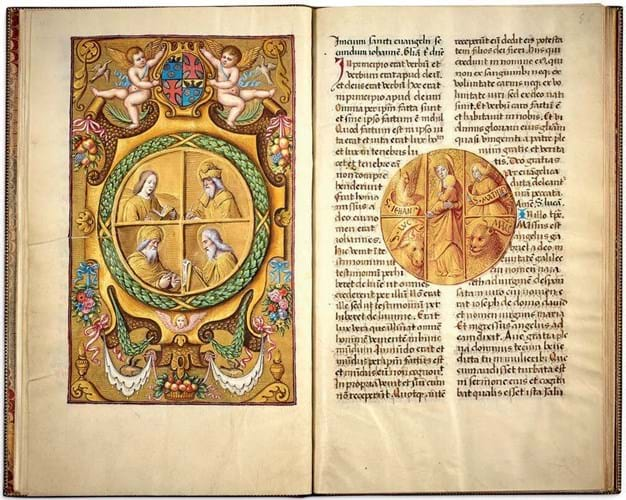

Other highlights

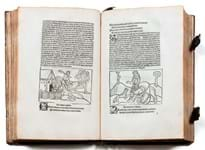

Claude Aguttes’ favourite item in the Aristophil collections was the Petau Book of Hours sold at €3.35m (£2.95m), more than four times the top estimate in June 2018. With premium added the price was €4.29m (£3.77m). It takes its name from the Petau family of bibliophiles – the arms of Alexandre Petau (1610-72) appear inside – but was probably decorated c.1495. The 16 medallions in gold camaïeu are probably by Jean Poyer of Tours (fl.1490-1520), whose patrons included Anne of Brittany and her two royal husbands (Charles VIII and Louis XII). The attribution was made by Mara Hofmann in the 2004 catalogue raisonné Jean Poyer: Das Gesamtwerk. In the collection of Baron James de Rothschild (1792- 1868), whose arms appear to the Victorian morocco binding, and later owned by the French industrialist Paul- Louis Weiller (1893-1993), it had last sold in Paris by Gros and Delettrez in April 2011 when it took €1.8m. Under contract, Aguttes was not allowed to buy any of the Aristophil items as a souvenir during the 56 sales. “I wish I could have done it but just being able to see and handle these fantastic books and rare manuscripts was a real privilege for me.”

Image copyright: Aguttes/Drouot

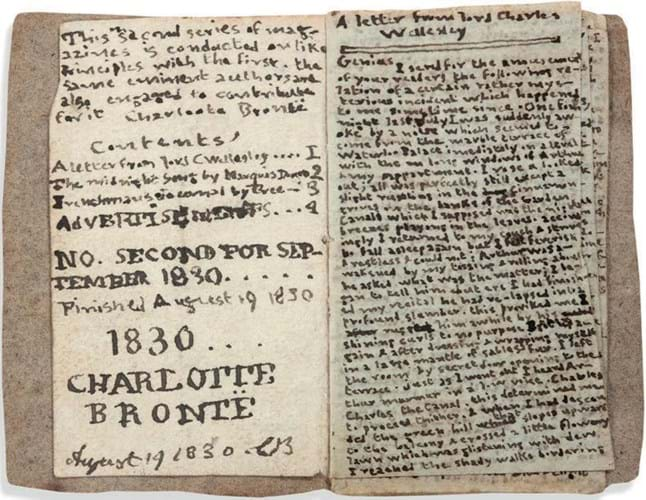

When The Young Men’s Magazine, Volume 2 dated August 1830 – penned by a 14-year-old Charlotte Brontë (1816-55) – was offered for sale in 2011 it was bought by Gérard Lhéritier for a pemium-inclusive £690,850. with the Brontë Parsonage Museum the disappointed underbidder. The museum was better prepared when the miniature manuscript returned for sale on November 18, 2019, as part of the Britannica Americana sale. With the help of the Brontë Society, some generous donors and crowdfunding, the museum was able to buy the book at €780,000 (£680,650). Written in minute characters in imitation of print, the tiny hand-sewn book measuring 1½ × 2½in (3.5 × 6.1cm) is one of a series of ‘magazines’ created by siblings Charlotte and Branwell Brontë from January 1829 to September 1830. Like others in the series, the prose and poetry are based in the imaginary west African settlement of Glass Town, with the characters based on a set of 12 wooden soldiers bought by Rev Brontë for Branwell in 1826. The books were supposed to have been produced and read by the toy soldiers, hence their tiny size.

Image copyright: Aguttes/Drouot