To be offered by Potburys (18% buyer's premium) of Sidmouth, it is part of the library of the late Dr Michael Charles Faraday Proctor (1929-2017), a renowned botanist, ecologist, author and Reader in Plant Ecology at Exeter University.

That library mostly comprises textbooks, journals and other academic publications that date largely from the mid 20th century to recent times, but among earlier items are two that bear the name of Henry Bradbury.

Valued at £1500-2000 is Thomas Moore & John Lindley's Ferns of Great Britain and Ireland of 1855, a well known work published by Bradbury & Evans that contains 51 ‘nature printed’ plates.

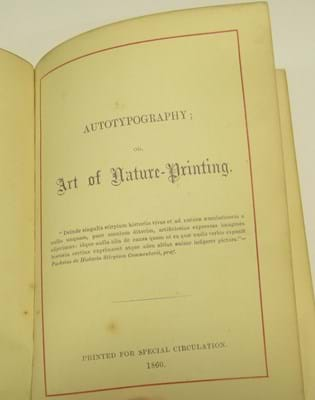

Copies have made as much as £6500 at auction – and on March 8 an example with many of the plates loose made £2000 in a Lawrences of Crewkerne sale – but I could find no auction record for Henry Bradbury's Autotypography..., a promotional work he had "printed for special circulation" in 1860.

The British Library and the Grolier Club in New York list copies of what appears to be a notable rarity in their catalogues, but what first aroused my closer interest was a note in that of the Edward Clark collection in Edinburgh's Napier University library.

"This rather insignificant-looking little book gave us quite a surprise. We received a question about a different book by Henry Bradbury, and responded mentioning that we had this one.

“The requester emailed back to say that he had been looking for a copy for 20 years! The British Library’s copy appears to have been destroyed in World War II, and we are not so far aware of another source.”

Ferns of Great Britain... employed a nature printing technique, invented by Alois Auer and Andreas Worring in 1852, one that involved pressing a leafy specimen onto a thin, soft lead plate and thus producing a finely detailed intaglio impression.

Bradbury had studied Auer's discovery in Vienna, but then patented his own version in London without any acknowledgment. Unsurprisingly, something of a controversy followed.

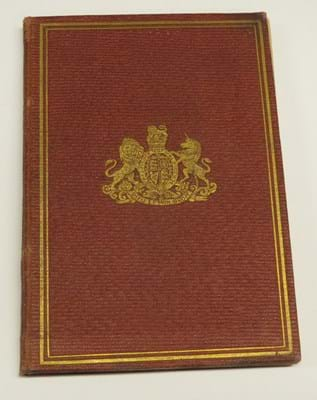

In this little work, which in its cover armorial reminds readers that the publishers enjoy the privilege of a royal warrant, the principal aim is to promote and provide detailed accounts of the various works published using their process, incorporating correspondence and testimonials from satisfied customers and other self-promotional material.

In the opening pages, however, Bradbury also takes the opportunity to address and contest the claims levelled at him regarding the invention of the process.

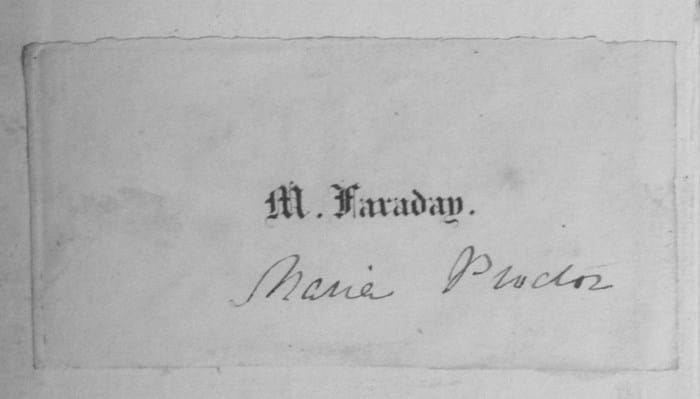

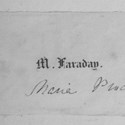

Bradbury would have sent out many promotional copies of this work, seeking approval and publicity, but of particular significance in this copy is a simple bookplate or label that identifies it as a copy originally owned by the distinguished British scientist Michael Faraday.

Beneath Faraday's name is that of his niece, Maria Proctor, an ancestor of Michael Charles Faraday Proctor, from whose collection it came to auction. It is estimated at £150-250 but that significant provenance could well prove financially rewarding.

The sad ending to this tale is that Bradbury, aged just 31, committed suicide in the very year that saw the publication of the little work being offered in the Devon sale.