"I wanted to make my mark as an art dealer, to do something original, proselytising what I knew was great art and seemed to me under-appreciated. If it wasn’t going to work, I would rather have gone on the run than stick with a business just because my father and grandfather were rather good at it.”

Paul Moss, owner of Mayfair dealership Sydney L Moss, has a clear opinion about what ‘great’ Asian art is all about. And it isn’t the imperial porcelains or stonewares that had earned his grandfather the epithet of ‘the king of Junyao’.

There was, he said, no great eureka moment – more a gradual understanding that what really rocked his boat often lay outside traditional London art market favourites.

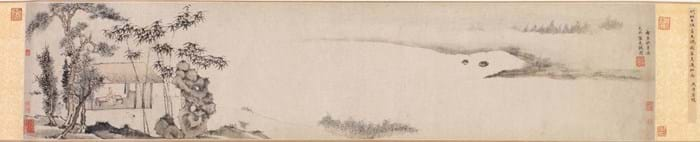

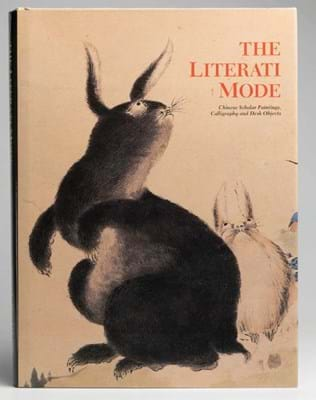

“It was the stuff I kept on falling in love with, kept making all sorts of wonderful new discoveries in,” he recalls. That stuff was literati Chinese arts – painting, calligraphy and objects conceived in organic materials in the scholar’s taste – and the arts of Old Japan, notably netsuke, inro and other sagemono.

It is the gallery’s narrow focus on the artist as an individual that gives it a distinct character.

“I don’t particularly care about Chinese imperial ceramics because they lack that dimension of the artist’s personality. It may be wholly admirable in many ways but I’m afraid I get bored with the same thing over and over. It doesn’t matter how technically perfect it is. I want it to ring my chimes.”

It was also a conscious decision to do something different in an evolving market.

“By the time I made that cut, it was getting obvious that the heights of the Chinese market were painfully expensive and getting more so. We didn’t have backers or deep family pockets; we had to pay our way with a bank overdraft. In that sense there was never an element of choice about it.”

The Sydney L Moss team. From left to right: Ashley Gallant, Finn Daley Roberts, Paul Moss, Hortense Marandet, Georgia Leach and Oliver Moss.

Temple Hopping

Moss left Durham University in 1973 supremely confident about his future but not wholly sure of the direction it might take. “I didn’t know what I was going to do but I knew it was going to be a work of art.”

He’d already taken a student sabbatical to become a town councillor and later taught himself more than 10,000 Chinese characters via flashcards to aid with a dissertation on Tibetan thangkas.

“I do this for every day being different, for the expectation of coming across something really good, for our research projects and for the likelihood that any new people interested in our chosen fields are likely to be good people.”

Paul Moss, proprietor of 107-year-old London dealership Sydney L Moss

It was a temple-hopping tour of Asia in 1977-78 that crystallised his plans to throw in his lot with the art world. He spent his recovery from water-borne hepatitis in Hong Kong, with his uncle Hugh Moss, creating a card system recording the names of Chinese artists and artisans.

The laborious endeavour (later the basis of the 1986 Hugh Moss/Gerard Tsang exhibition catalogue Arts from the Scholar’s Studio) showed an aptitude for research and taught a simple lesson.

“When you write it down you learn it,” he says. Some three decades years later when Oliver, 34, the oldest of his three children, completed his studies in east Asian culture and joined the gallery, he too was set a similar task to create a database of old Chinese painters.

Moss senior, now 66, wears the mantel ‘custodian of the family business’ lightly.

“Of course I’m proud that we are the oldest Asian art dealership in London. I think it’s extremely cool that I shall hand over the reins of directorial control to Oliver next year (2018) on the 108th anniversary of the company’s foundation.

“But it’s not something that occurs to me when I ask ‘what am I doing this for’ as I ponder life over the muesli. It isn’t for the family business. It’s for every day being different, for the expectation of coming across something really good, for our research projects and for the likelihood that any new people interested in our chosen fields are likely to be good people.”

He had known his grandfather reasonably well. According to family lore, Sydney Leonard Moss (1893-1980), an amateur watercolourist, talented tennis player and professional ceramics restorer from Wimbledon, had been encouraged to become a dealer in 1910 by the orientalist and private banker George Eumorfopoulos (1863-1939). “Do you require some seed money?” the banker had asked.

It was a pregnant moment in Western collecting: The Exhibition of Chinese Art at Burlington House in London, the first of its kind in the UK, was followed by the collapse of the Qing dynasty and the years of unrest that would bring the treasures of the Chinese court to market.

Moss retells two anecdotes that speak something of his grandfather’s character: an “uncharacteristic generosity” with cigars when learning his grandson had achieved a first in his degree and then his refusal to allow the original ‘poor little rich girl,’ Woolworth heiress Barbara Hutton, to return to the gallery when he discovered that she was using Roman glass dishes for ashtrays. “He was an Edwardian in outlook – of the generation that always wore a hat outdoors.”

His father Geoffrey Bernard Moss (1925-79) had been a study in contrasts.

“My grandfather had a broker. My father carried around huge amounts of cash,” is how Moss frames it. Geoffrey Moss was known in the trade as a born salesman whose every pocket was filled with rolls of banknotes and the netsuke he introduced into the company inventory. But he died young and just two years into Paul’s full-time tenure with the firm.

“I tell people interested in Edo period Japanese culture to take good, long looks at China”

Recent succession planning has taken him back to that precipitous moment of shifting responsibilities.

In at the sharp end, in his 20s, Moss quickly emerged among that rare breed of merchant academics, comfortable moving between the grubby world of commerce and a more ‘noble’ calling. Unlike the museum curator, dealers, he attests, “need to be alert on all channels at once, never forgetting that vital money channel.”

He made some of his first major ‘solo’ purchases in the Chinese painting field at auctions of the collections of US dealer Howard C Hollis (1899-1985) and the orientalist, diplomat and guqin player Robert Hans van Gulik (1910-67).

At the latter, held in the relative obscurity of Christie’s Amsterdam in 1983, he bought 30 lots. “I stopped when I knew I couldn’t carry any more,” he recalls. Among his purchases was a painting of musicians by Choson artist Kim Hong-do, also known as Danwon (1745- c.1806), later sold to the British Museum.

Other institutional clients followed. Through relentless travel and catalogues conceived both as visual entertainment and serious reference works he fostered strong relationships, particularly with American collectors and curators who “spoke my language”.

Boisterous professional rivalries emerged too, the late Barry Davies his self-confessed nemesis. Moss admits he feels compelled to be outspoken on the issues that affect his backyard. “We [Sydney L Moss] do tend to regard ourselves as something of a policeman. It is not always a popular thing to be.”

Orientalist

The gallery is today a rare advocate for the duality of Chinese and Japanese arts – a 21st century version of the waning Western concept of the orientalist.

“I keep telling everyone I know interested in Edo period Japanese culture that they would gain exponential understanding if only they would take good long looks at China. We just keep coming up with irresistible derivations and moments of enlightenment by seeing both fifty-fifty.”

A recent exhibition of painting and calligraphy from the Obaku Zen school, rooted in the arrival of Fujian monks in Nagasaki in the mid-17th century, made the point well. However, he concedes that – with the honourable exception of a handful of collectors deeply interested in plural cultures – the audience is now “largely one or the other”.

“My expectation was that when old Chinese painting, for example, went beyond the means of the average successful professional, we would see such people switching in their droves to the fascinating and incredibly available Japanese equivalent. That hasn’t happened.”

Trade is, in short, unrecognisable from the days when his forebears would “buy it at auction in the morning, wash it and ticket it over lunch, and then sell it in the afternoon”.

Elements of the Japanese marketplace have famously softened with economic forces and what Moss calls “some indefinable zeitgeist stuff”. He recalls the period after The Great Japan Exhibition at the Royal Academy in 1981, when “you couldn’t move for serious Japanese art collectors” to the moment after the 1990 crash when “the Japanese withdrew unto themselves and, in the eternal words of Mick Jagger, you couldn’t give it away on Seventh Avenue”.

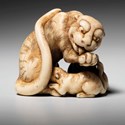

In some micro-markets that becalmed stretch continues. Others, such as the best netsuke, have been largely immune.

“For Japanese art we still operate as proper dealers. We buy and sell collections.”

Red Tape Checks

Moss speaks of “turning our eyes back to Europe” in search for new clients – a convert to the TEFAF Maastricht fair where the firm debuted two years ago. It reflects in part the onerous cultural heritage and ivory legislation that is checking the movement of works of art around the world. There’s also a desire to perpetuate a venerable London trade.

“There was a time when selling a work of art to two or three leading Hong Kong collectors was my litmus test of whether I’d made it as a dealer. Then I realised that I’d never see those great works of art again.”

The age-old London trade model, buying back prize items of stock from the next generation of owners, is fast fading in the Chinese market.

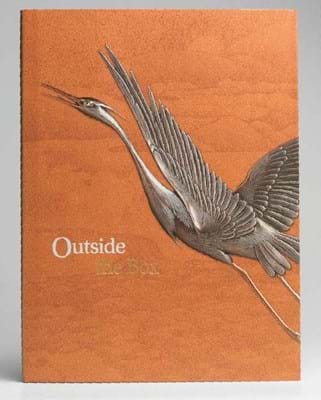

A ‘box’ or hako netsuke by Shibata Zeshin (1807-91) with lacquer bowl and a bamboo lid, decorated with gold, black and brown lacquer chrysanthemums. Priced at £11,500 at Sydney L Moss.

“For Japanese art we still operate as proper dealers. We buy and sell collections. We maintain a deep and high-class stock. For Chinese works of art the auction room rules.”

Nonetheless, Sydney L Moss is one of the very few galleries dealing in classical Chinese paintings, filtering a small number of works and studying them in depth “rather than jumping on the bandwagons of availability and marketability”.

Oliver particularly enjoys the challenges posed by this idiosyncratic space. “Finding the paintings that give us a reason to fight against the hoovering-up force that is the Chinese market is the exciting part of the job. Attribution and authenticity gets you about a third of the way. Often what makes it special is context. Each painting or calligraphy is individual and unique, and becomes its own detective project.”

Passing the Baton

It was the departure of long-standing staff in the 100th anniversary year that forged what Paul Moss describes as “the most dynamic handful of proto-experts currently in intensive training”.

Alongside Oliver is Finn Daley Roberts, Ashley Gallant, Hortense Marandet and recent recruit Georgia Leach. Hortense is the one link – alongside Paul – with the old regime.

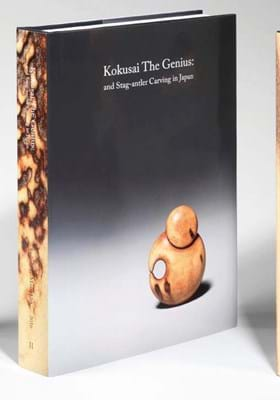

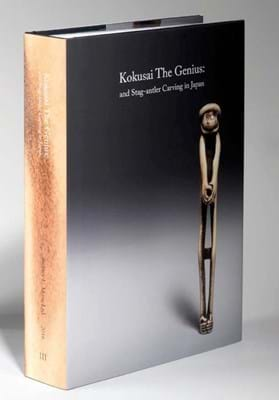

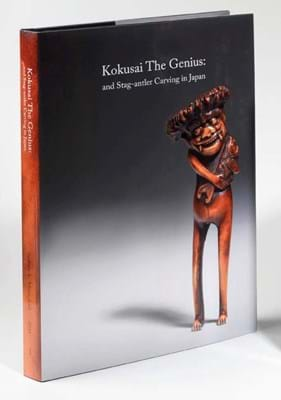

Under guidance – what Moss describes as “a back-and-forth collegiate approach” – Roberts and Moss junior in particular made significant contributions to the three-volume magnum opus, Kokusai The Genius. “It wasn’t a question of me giving the team a specific agenda,” Paul Moss says. “It was more holding an old handkerchief to the bloodhound’s nose and watching them go.”

Has the firm moved in a new direction with their input? “It’s early days for that. I encourage it, but it’s still a question of me bestriding my indulgences like a colossus. Art dealers are one-man shows. That’s the way it is.”

The temptation to deal in contemporary material is not strong. “Our response to the shrinking supply of the best period works is to buy it anyway. Like most arrogant, unreasonable approaches, it works quite well,” he quips.

Netsuke masterworks arrive weekly: a recent holiday in Greece presented a chance to repurchase a kurogaki netsuke of a rat on an inkcake by the Iwami school carver Seiyodo Tomiharu (1733-1811).

A visual and intellectual highpoint among the 100 netsuke from the Willi G Bosshard collection sold by the gallery in 2008, it is now safely back in Mayfair.

“We can continue to fill a gallery year-round with great old art, ringing the changes with sub-shows and new displays,” Moss concludes. “I like that stuff a lot better than I like the contemporary alternative.

“For the short time remaining with me running the show, that’s the way we play it. No compromise. I’ll leave it for the next generation.”

“I feel more of a sense of duty and burden than my father did. I am a lot less rebellious than he was.”

Oliver Moss, 34, who assumes control of the firm in 2018

Good enough to publish and tell a tale

A library of catalogues provides the most tangible legacy of the past four decades of dealing at Sydney L Moss. The current proprietor is a firm adherent to the New Testament creed By their works shall ye know them.

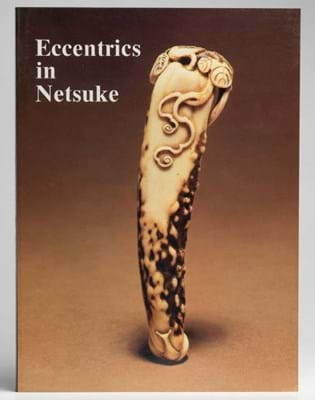

Moss’ first serious foray in publishing was the 1982 Eccentrics in Netsuke, a soft-cover catalogue – now considered something of a mini classic – with contributory essays from various luminaries on the work of eight carvers. Its merits were underlined later during a netsuke convention in Hawaii when a collector new to the gallery who had marvelled at its content immediately spent $200,000.

Moss stuck a sign on the hotel door ‘gone to the beach’, where other collectors found him and his remaining stock chilling under a palm tree.

Dealer catalogues provide cultural and artistic context to objects for sale. They can also reflect something deeper – the desire to evangelise, proselytise, decipher, undo misconceptions or simply tell a good tale. Selling tool or telling stories, “the two aspects live together in the same bedroom”, Moss says.

“What we deal in has some fairly stacked cultural content, and you can either let people work it all out for themselves, or you can save a lot of time and tell them. We need a clientele that gets it. But yes, I enjoy writing about works of art.”

‘Serious Art’

The titles of one or two catalogues across the years – Only Fittings and Netsuke: Serious Art to name but two – suggest a belief that elements of the Asian art market are yet to acquire academic gravitas. Moss makes no apologies.

”The Japanese applied arts are not treated seriously by nearly enough art historians. No question. My partisan conclusion is that it remains misunderstood, under-appreciated and – with some noble exceptions – actually looked down on by most curators.”

Publishing at Moss recently crescendoed with two ambitious projects. Six years in the making, 2010’s This Single Feather of Auspicious Light, dedicated to Chinese painting and calligraphy, amounted to the largest art dealer’s catalogue ever produced, the multiple volumes in bespoke case weighing in at a mere 28kg.

The long-awaited trilogy of books dealing titled Kokusai The Genius and Stag-antler Carving in Japan followed in 2016-17 – the culmination of fascination with the eccentric Meiji carver that began when, as a schoolboy, Moss would pocket a Kokusai owl netsuke to show his art teacher.

Even with an eye on retirement and a yearning for long sojourns in Japan, there may be “another book left in the old man”. The great Osaka netsuke carver Ohara Mitsuhiro (1810-75) is an artist Moss describes as “a bag of treasures”.