For antiquities aficionados, the pinnacle of Christie’s ‘Classic Week’ in New York was its single-owner offering of 40 exquisitely carved intaglios and cameos hailing from the ancient world.

The collection – offered under the title Masterpieces in Miniature – was described before the sale as “assuredly the most important group to appear at auction in over a generation” by Max Berheimer, Christie’s international head of antiquities.

It did not disappoint. On April 29, all 40 pieces found new buyers, mostly in North America, with the majority making well in excess of estimates to the tune of $8.63m (£6.69m).

As reported on the front page, the J Paul Getty Museum in California was the primary purchaser, acquiring 17 lots and spending over $7m.

Three pieces from the group sold above $480,000 – the previous auction record for a Classical gem, achieved at Sotheby’s in 2016 for a Roman carnelian intaglio now in the Getty Villa in Malibu.

Composed of mainly Greek and Roman gems from the late 6th century BC to the 1st century AD, engraved with motifs of mythological figures, animal studies and portraits, the group at Christie’s was previously owned by Giorgio Sangiorgi (1887-1965). He was a renowned collector, dealer and scholar in ancient, medieval, and Renaissance art, who amassed most of it in the early to middle years of the 20th century.

Before that, many had been in the vast collection of gems acquired by the 18th century nobleman and politician, George Spencer, the 4th Duke of Marlborough, whose highly prized collection was sold by Christie’s in 1899. Cameos and intaglios were a favourite souvenir for Grand Tourists such as Spencer, who commissioned the artist Joshua Reynolds to paint him with a prized cameo of the Roman emperor Augustus.

Adding to its appeal, the Sangiorgi collection had recently been published by English scholar John Boardman and Claudia Wagner.

In the ancient world, engraved gems in precious or semi-precious stone were highly prized, rivalling monumental marbles, vases and bronzes in terms of artistic skill. Such museum-quality collections are excessively rare on the antiquities market today, evidenced by the intense bidding this collection attracted in New York.

This was assuredly the most important group to appear at auction in over a generation

Marlborough ownership

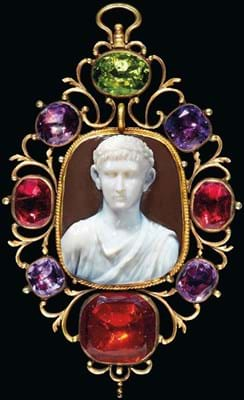

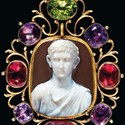

The group was led by the so-called ‘Marlborough Antinous’, a famous gem from antiquity in a Renaissance period gold mount named after its illustrious former owner, the 4th Duke of Marlborough. The Getty was the buyer.

The high-quality engraving – akin in detail and modelling to a full-size marble bust – is one of the only known authentic contemporary portraits of Antinous, the beautiful Greek youth who became Emperor Hadrian’s favourite and achieved god-like status after he drowned in the Nile in 130AD.

According to the catalogue, the mania that this “unusually large black chalcedony intaglio inspired” was so great that its first documented modern owner, Anton Maria Zanetti (1679-1767), said he would have sold his house to buy it.

Centuries later at Christie’s, two bidders showed similar resolve to procure it. Against a $300,000-500,000 guide, it was pursued over the course of three minutes before the hammer eventually fell at $1.75m (£1.35m) – a new record for a gem from the Greco-Roman world.

A Roman black chalcedony intaglio portrait of Antinous with missing portions restored in gold – $1.75m (£1.35m) at Christie’s New York. It sold to the Getty.

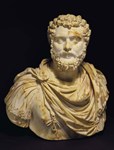

This is not the first time a likeness of Antinous has sparked fierce bidding on the rostrum. In 2010, a Roman bust billed as the only known classical representation of the Greek youth identified by a complete inscription (outside his coin portraits) sold for a huge $23.8m (with fees) at Sotheby’s New York from the collection of American antiquities collector Clarence Day. It had been estimated at $2m-3m.

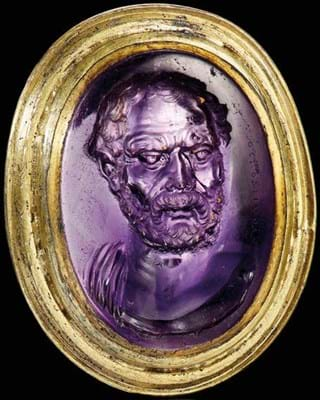

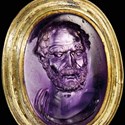

The other seven-figure sum at Christie’s was paid for a Roman amethyst ringstone portrait of Demonsthenes, the 4th century BC Greek orator. It was signed Dioskourides, a gem engraver par excellence who worked for the Emperor Augustus.

Just six other intaglio gems and one cameo survive bearing Dioskourides’ signature, while several others are assigned to him on account of quality and style.

The amethyst – described in the catalogue as so deeply cut in high relief that “it nearly reads like a statue in the round” – has been well documented since the Renaissance, passing through the hands of many eminent ancient gem enthusiasts. It was seemingly the one Flemish artist Peter Paul Rubens saw while visiting Rome, recording the inscription in his diary. Later, it was later acquired by Sir Arthur Evans (1851-1941), the famed excavator of Knossos and Keeper of the Ashmolean Museum, who sold it to Sangiorgi in 1941.

Mounted in an antique gilt silver frame, the piece drew multiple bids against its $200,000- 300,000 estimate before it was knocked down to the Getty at $1.3m (£1m).

Not only perhaps the finest single Classical study of the hero but one of the best engraved gems of its period

Roman cameos

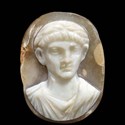

Two Roman cameos in impressive 18th century jewelled mounts – one of the goddess Isis and the another of a Julio-Claudian Prince, possibly Germanicus – sold to different buyers for multiples of their guides at $350,000 (£270,000) and $280,000 (£220,000) respectively. Both were formerly in the collection of the antiquarian William Ponsonby, the 2nd Earl of Bessborough, whose impressive collection of cameos and intaglios was later sold to the Fourth Duke of Marlborough.

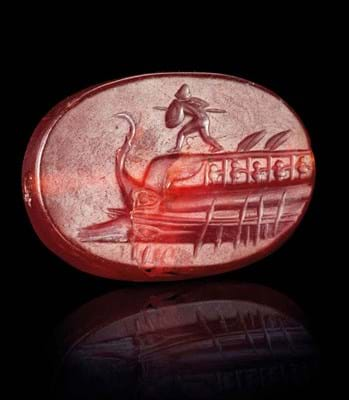

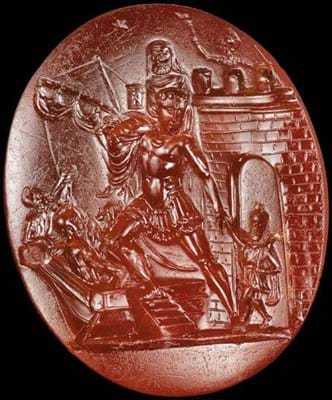

A similar level of bidding also emerged for a ringstone carved in the 1st century AD with a detailed scene of the Roman hero Aeneas carrying his father and leading his son out of the gates of Troy. It took $400,000 (£310,000), another item on the Getty shopping list.

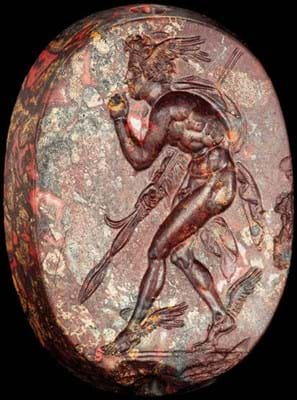

Perseus as a gem

Greek gems made up around half of the collection and were led by a scaraboid engraving of the muscular hero Perseus tiptoeing towards the snake-haired Gorgon, Medusa. The c.4th century BC piece was described by Boardman and Wagner as “not only perhaps the finest single Classical study of the hero but one of the best engraved gems of its period”.

Engraved on mottled red jasper, itself rare, it took a multi-estimate $700,000 (£540,000).

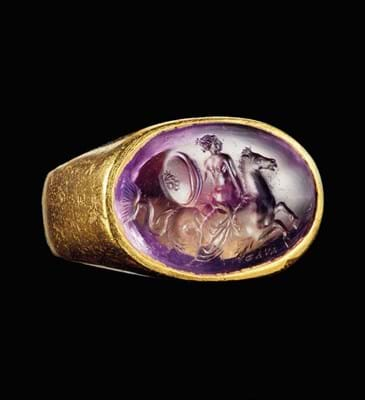

The club-wielding Greek hero, Herakles, featured on a 24-carat gold finger ring that took $320,000 (£248,000) against a $30,000-50,000, while a red carnelian scaraboid of Protesilaos – the first Greek warrior killed in the Trojan War – made over three times its top guide at $260,000 (£200,000).

A Greek mottled yellow jasper scaraboid with a grasshopper – $420,000 (£326,000) at Christie’s New York. It sold to the Getty.

A meticulous study of a grasshopper on a grass stem, which shares close similarities to another found in the British Museum, was knocked down at $420,000 (£326,000). The mottled yellow jasper scaraboid was attributed to the gem engraver Dexamenos of Chios, whose signature is found on just four known gems. All were purchases for the Getty Museum.

Towards the more ‘modest’ end of the price scale, a 1st century Roman sardonyx cameo of a Julio-Claudian prince wearing a laurel wreath achieved $19,000 (£15,000), while two Greek carnelian scarab beetle seals of a youth shouldering a ram and a cricket, sold for $24,000 (£18,600) apiece.

£1 = $1.29