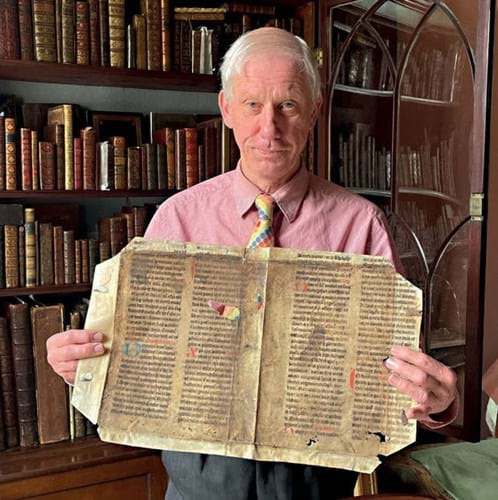

An early purchase by Robert Weaver. A “really tatty” interior of a leaf which was ripped up during the Reformation.

ATG: How did you get the collecting bug?

Robert Weaver: I’ve always had it, starting with stamps and then moving onto second-hand books. I am an acquisitor by nature in the ‘hunter gatherer’ tradition.

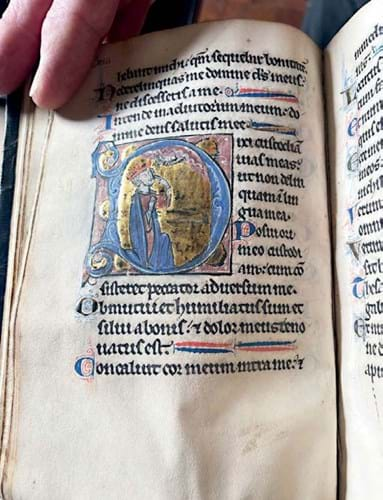

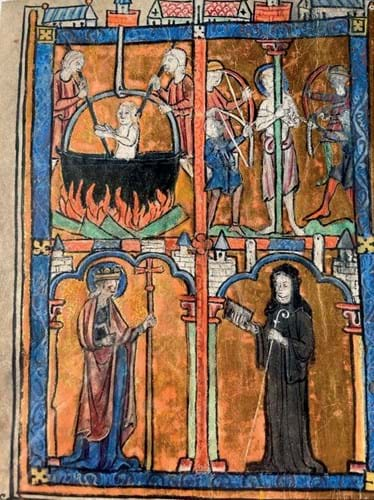

A leaf from a 14th century pontifical book with a picture of a bishop presiding over communion. “An expensive thing for me because of the picture… If this sold in the market today it would be several thousand pounds.”

Why medieval manuscripts?

I took a student intern job at the British Museum some 50 years ago and got hooked on their large displays of medieval complete manuscripts in the Grenville Library. It was love at first sight.

What is your focus within the field?

Fragments. It started when I realised that I could afford to buy the single leaves and scraps from dealers and auction houses. When I was 22, I learnt that Sotheby’s had a department of medieval manuscripts and Christopher de Hamel was the expert.

I went to see him and asked if you could just buy the odd leaves and my collection was started. Christopher, now a friend of mine, brings his guests to mine as a sort of museum piece and often says: “Everything in your house is cracked, Robert, even the owner.”

What was the first thing you bought?

A Victorian scrapbook of cuttings of initials from Italian choir books bought from Sotheby’s for £120 in 1977. A Victorian child had cut up a manuscript (which of course is terrible but it’s what they did). I saved up to buy it and still own it buried somewhere in my house.

How many items are in your collection today?

I now own around 200 leaves with three complete-ish books.

What sort of manuscripts are represented?

Because of expense, I was originally confined to church stuff. Nonreligious material is today quite rare, but lots were made for church services and for people to possess a book of prayers.

Most of mine are in Latin, some are in French and Hebrew. They are mainly single leaves on vellum from the 12th-15th century church service books, which fell foul of the Reformation. I’m drawn to their gothic scripts but also their fantastic scribal illumination. Now I’m older, I’ve got savings that I can put into buying a whole book of decorative material, but it’s nice to have a wide range of examples instead of just one.

Do you come into contact with other collectors?

There aren’t many of us collecting fragments, but I know a number of other collectors and we meet in the auction rooms and see each other’s collections and swap pieces.

An illumination with retouched faces. “They’ve wrecked it completely. I paid about £4000 because it was a big medieval picture but not many others wanted it because it had been damaged. If this was in spanking condition it would be £50,000.”

Over the years it has been a common practice for dealers to take full works and split them up to make them more saleable. Given your interest fragments is this something you support?

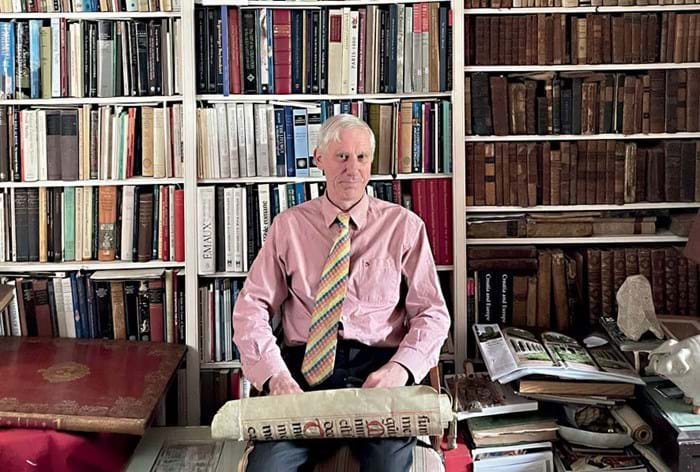

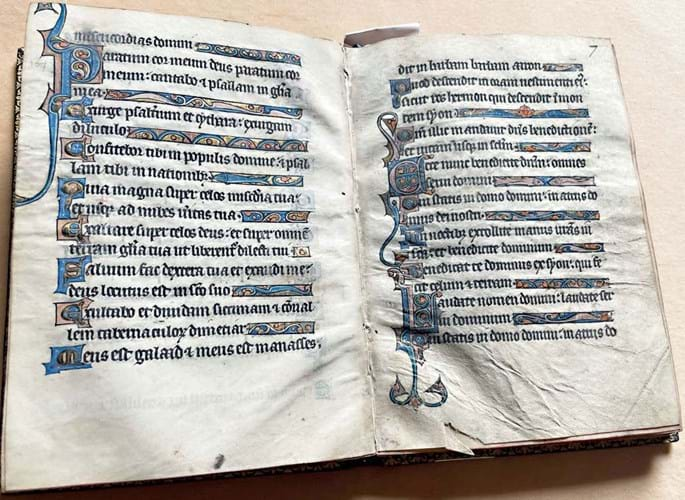

No. Sadly, because of the Reformation and later because of dealers splitting them, many works have been cut up. For ethical reasons, I try not to buy if something has been cut up recently to my knowledge. I’ve got one book that I saved from being split because a dealer was going to buy it and split all the pages up for profit.

It was a 13th century book that had already been split into three parts that was in one of Christopher de Hamel’s auctions at Sotheby’s. It had 50 leaves and was highly decorated. I knew that it was the sort of thing that breakers buy.

“A little book that I stopped being split up. It cost me about £4000 when I bought it and I’ve had it for 30 years.”

Where do you go to buy these days?

A few dealers stock manuscript leaves – Maggs and Quaritch at the top end – but I also buy from book fairs, and twice yearly at Christie’s. I now look for items that fill gaps in my collection. I still yearn for examples of rare scripts like the extraordinarily quirky Beneventan texts of southern Italy.

What is the most expensive item in the collection?

Three complete or nearly complete manuscripts, highly illuminated with initials and miniatures. I have two 13th century Psalters and a Book of Hours c.1400.

What is one great discovery you’ve made?

A 16th century printed medical text owned, according to an inscription, by a Venetian doctor practising in Croatia, then a colony. I bought it on a hunch from a dealer specialising in racing books. Bound around it was a tatty sheet using an extraordinarily weird alphabet on vellum. The script turned out to be in Glagolitic, a cross between Cyrillic, Hebrew and other alphabets with loads of invented box-type letters. At that time it was banned by Venetian overlords.

Only four such items have been recorded at auction in Britain in the last 200 years, so its rarity is undoubted. The doctor clearly ripped the leaf from its parent manuscript in Croatia, took the newly bound book back to Venice where it later was taken as booty by Napoleon and landed up in Vienna at a Franciscan friary which was secularised in 1805. After that its history is obscure.

How do you display your collection at home?

I don’t tend to show my leaves on walls in the home. I store them in acid-free board mounts or between acetate sheets.

Do you ever sell items on?

Not often. An occasional prune of material at the lower end is timely, but there again every fragment, however humble, has its own history uniting us back to a world very different but all still very human.

How does collecting inform your work?

After a teaching career, my current role is to curate the antiquarian books at Dulwich College. I relish doing show-and-tell sessions for students, staff and the interested public, and frequently bring in relevant material from my collections to illustrate the history of writing.

I enjoy tailoring what I’ve got and handing things round. I say: ‘A cow was walking around 500 years ago, someone skinned it, processed it to get what we have here.’ Collecting can be a secretive business for some but I enjoy sharing what I am lucky enough to possess.

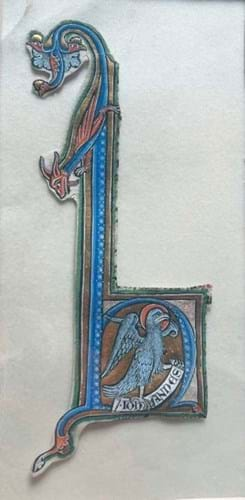

A letter H cut to shape, c.1210-20 by the Almagest master. “An Italian dealer sold it to me about 10 years ago. It was in his stock just lying at the bottom of a pile. He thought ‘well it’s only a cut out’ but the quality is superb so that’s the fun of it. I think a Victorian child did the cutting out, very carefully.”

What are your plans for the collection?

They’re quite difficult to bequeath to institutions and mine aren’t really ‘special’. If there was a lovely remote cathedral or something that would benefit from one rather good thing, I would give them it.

I suspect now I’m going to do what’s called a Goncourt. The Goncourt brothers said ‘all our wonderful collections in Paris are going to go back on the market to give everyone the pleasure of buying them again as we did’.

Do you collect anything else?

‘Fraid so! Chinese pots, English topographical watercolours, early modern bookbindings, and wine, for starters.

What is your advice to new collectors?

Find a virgin field to delve into and trailblaze.

In my rather recherche field, my advice would be to start with assembling a handful of quite plain medieval single leaves showing script types, or leaves from a particular country, or those with a certain decoration or particular text.

Medieval manuscripts are a fairly well-worn path in book collecting and the better examples have always been expensive, but with care a representative selection of leaves might still be built up. There is always the possibility of ‘the find’ to keep the adrenalin running.